Jonathan Rowson

Feb 9th, 2021

‘There is a process of reckoning going on around the world, heightened by the conditions of the pandemic and the palpability of our fragility, inequality and interdependence. There is a climate emergency that requires urgent action, but the precise nature, cost, location and responsibility of that action is moot. There is a broader crisis of civilisational purpose that appears to necessitate political and economic transformation, and there are deeper socio-emotional, educational, epistemic and spiritual features of our predicament that manifest as many flavours of meta-crisis: the lack of a meaningful global ‘We’, widespread learning needs, self-subverting political logics and disenchanted worldviews. These different features of our world are obscured by their entanglement with each other. It is difficult to orient ourselves towards meaningful action that is commensurate with our understanding because we are generally unclear about the relationship between different kinds of challenge and what they mean for us. That’s what this essay is about. The world is in a pickle, and, daunting though it is, we need to learn how to taste it. Tasting the pickle well requires, in the spirit of Vivekananda, finding joy and releasing energy through the right kinds of discrimination’.

– Jonathan Rowson

Tasting the Pickle is the first in Perspectiva’s new essay series and the writing is deliberately essayistic in spirit, ambitiously trying to achieve several aims at once, and not expecting to fully succeed.

Tasting the Pickle is an adapted version of a book chapter in the forthcoming compilation: Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and Emergence in Metamodernity, published by Perspectiva Press in Spring 2021.

Read & download the essay as a PDF here: Tasting the Pickle – Ten flavours of meta-crisis and the appetite for a new civilisation

The full essay is also available to read below.

Tasting the Pickle: Ten flavours of meta-crisis and the appetite for a new civilisation

Jonathan Rowson[1]With thanks to Bonnitta Roy, Mark Vernon, Layman Pascal, Ivo Mensch, Hannah Close, Ian Christie, Minna Salami, Jeremy Johnson and Zachary Stein for their feedback on various drafts of this essay.

I am not sure I am worthy of a spiritual name because for the last decade I have lived a bourgeoise family life in London and enjoyed my share of boozy dinner parties. Yet there is a corner of the world where I am officially Vivekananda, a name conferred on me somewhat hastily in 2016 at a nondescript temple that doubled as a religious office in Kerala, South India. I came up with the name Vivekananda myself, which is not how it’s supposed to happen. I liked that it means discriminating (vivek) bliss (ananda) because it chimed with my experience of getting high on conceptual distinctions; my wife Siva and my Indian in-laws agreed it was fitting and I was sent to photocopy my UK passport in a nearby booth on the dust roads. I returned with a piece of paper that detailed what I was ostensibly about to surrender, and it happened a few minutes later on a cement floor with chalk drawings, where I sat cross-legged under a ramshackle plastic sheet protecting us from the heat of the sun. I don’t remember the priest’s features and he didn’t speak English, but I knew the fire he created would be our witness, and when he invoked me to chant, those ancient Sanskrit sounds would resonate beyond that day. I was undertaking apostasy. This act of spiritual sedition felt political because it so often goes the other way in India, and I still feel the solemnity of that moment in my body. I did not seek to flirt with the sacrilegious and nor did I wish to renounce a faith I never really had, but I was sure that faith as such would always be my own, as would my Christian name.

I am still Jonathan, but technically renouncing my presumed Christianity to become Vivekananda was the only means by which I could be initiated into Arya Samaj (noble mission) which is a reformist branch of applied Vedantic philosophy within the religious orbit known as Hinduism. This conversion was neither doctrinal nor devotional, but it was undertaken quite literally to get closer to God, whom I hoped might exist, understand, and perhaps even laugh. After several years of sitting it out in a nearby air-conditioned hotel, the certificate I received after the ceremony was the only way I could, for the first time, join my family and enter the nearby pilgrimage site at Guruvayur, which is strictly for Hindus only, and purportedly Krishna’s home on earth. Whatever the fate of my soul, family pragmatics meant that my upper body was needed to carry our second son, Vishnu, and his abundant baby paraphernalia. I was never asked for my certificate, and were my skin brown I would not have needed it. Yet it was only because Jonathan doubled as Vivekananda that the rest of his family could pay obeisance alongside thousands of other pilgrims. I watched them queue for hours to see idols bathed in milk, offer their weight in bananas to God, feed the temple elephants, and pray. At one moment, tired but grateful, I looked down at baby Vishnu in my sling, not yet a year old, and it felt like the temple’s host was smiling back. I was there under false pretences, but those false pretences were true.

Swami Vivekananda was a celebrated spiritual figure and a disciple of the mystic Ramakrishna, which, curiously, is my father-in-law’s name, which he also chose for himself. Vivekananda was known, among other things, for receiving rapturous applause for the acuity of his opening line at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago in 1893: ‘Sisters and Brothers of America’, he said. That line seems quaint now, but it was catalytic at the time for a Hindu to speak in such resolute solidarity with an international audience, an encapsulation of the emergence of a global consciousness that now reverberates everywhere, though not within everyone. To become worthy of the name Vivekananda would mean learning to speak with similar precision and to delight in the power of the intellect in service of higher ends, a manifestation of Jnana Yoga. Spiritual names are often aspirational like that, reflecting latent qualities that might yet be realised. I am not worthy to use the name Vivekananda in that way, but I mention it here to atone for the pragmatism that acquired it, and to inform the spirit of what follows.

There is a process of reckoning going on around the world, heightened by the conditions of the pandemic and the palpability of our fragility, inequality and interdependence. There is a climate emergency that requires urgent action, but the precise nature, cost, location and responsibility of that action is moot. There is a broader crisis of civilisational purpose that appears to necessitate political and economic transformation, and there are deeper socio-emotional, educational, epistemic and spiritual features of our predicament that manifest as many flavours of meta-crisis: the lack of a meaningful global ‘We’, widespread learning needs, self-subverting political logics and disenchanted worldviews. These different features of our world are obscured by their entanglement with each other. It is difficult to orient ourselves towards meaningful action that is commensurate with our understanding because we are generally unclear about the relationship between different kinds of challenge and what they mean for us. That’s what this essay is about. The world is in a pickle, and, daunting though it is, we need to learn how to taste it. Tasting the pickle relatively well requires, in the spirit of Vivekananda, finding joy and releasing energy through the right kinds of discrimination.

The English word ‘pickle’ comes from the Dutch word ‘pekel’ but there are related terms in most languages. For several centuries vegetables of various kinds have been preserved in a brine-like substance like vinegar or lemon. Depending on where you are on the planet, ‘pickle’ is likely to evoke images of stand-alone gherkins, jars of pickled vegetables, or perhaps composite substances with fermentation or spice. Due to the south Indian influence in my family, I know pickle mostly as lemon, garlic, mango or tomato pickle, condiments reduced to intensify flavour, usually in small amounts at the side of the plate that enhance the whole meal (not all reductionism is bad!).

Whichever image or feeling is evoked by the idea of ‘the pickle’, one major point of the metaphor, in a time of difficult decisions, is to help avoid various kinds of sweet-tasting spiritual bypassing, by reminding us of the importance of good and necessary but challenging tastes in a satisfying meal – salty, sour and spicy.[2]Masters, Robert A., Spiritual Bypassing: When Spirituality Disconnects Us from What Really Matters, North Atlantic Books (2010) Pickles are also about the latter stages of a process that begins with ripening and it therefore highlights the will to preserve – to hold back entropy and decay. To buy time. The expression ‘in a pickle’ also alludes to difficulty in the sense of being as trapped, mixed up and disoriented as the pickled vegetables in a jar. The etymological fidelity of such claims matters less than whether the phrase helps us sense how we are all mixed up with myriad things, somehow stuck, entangled, and unable to change in ways we otherwise might. There are early uses of the term by Shakespeare that relate to being drunk, and sometimes being drunk while not knowing we’re drunk; and that’s also appropriate for our current predicament. Most people still appear to be running on autopilot with an outdated kind of fuel, drunk on ideas of progress, our own significance and the notion things will somehow be ok.

As my colleague Ivo Mensch put it to me, we’re collectively living a life that no longer exists.

For many years I took pleasure in the study of conceptual frameworks, diagrams and maps, and I was excited by developmental stage theories in particular.[3]Rowson, Jonathan, ‘The Unrecognised Genius of Jean Piaget’, Medium (2016) These days I sense that the wellspring of life is not cartographical in nature, but more like a quality of experience that we should not be too quick to define. I am still vulnerable to outbreaks of cartological hedonism, but I am now in remission, looking for new ways to think and write that allow me to apply my intellect in the service of qualities of life that are not merely intellectual. The idea of tasting the pickle flows from that incipient change of direction. Rather than produce a framework, the idea is to imbibe a distilled version of our historical moment, i.e. verbally warming up a set of situational ingredients to intensify their taste, and then, in ways that have to be unique to each of us, taking it in. The point of the practice is to make sufficient distinctions among the figuratively bitter, astringent, salty and sweet flavours of ‘the pickle’ we are all in to properly digest what is happening for us personally, and thereby improve our chances of living as if we know what we are doing, and why.

The pickle also alludes to unity in diversity – several tastes that are also one taste. A visual analogy to tasting the pickle is the song lyric from The Waterboys: ‘You saw the whole of the moon’, but the tasting of the pickle is key. I believe we expect too much from ‘vision’, as if sight alone could ever save us. The tasting in question is about introjecting world system dynamics rather than spiritual realisation, but there are some parallels to the ‘one taste’ (which is every taste) developed in Ken Wilber’s basic map of evolution from matter to mind to soul to spirit, and involution from spirit to soul to mind to matter. Much of the theorising in the meta-community is tacitly about evolution in the former sense, about the purported need to become ‘more complex’ to deal with the complexity of the world. Tasting the pickle is mostly about the simultaneous necessity of countervailing movement, so that we can return home from our exalted abstractions, even if we may need to head out again. Wilber makes the point that the process of involution happens at The Big Bang, when we are born, and most profoundly at every waking moment if we know how to grasp it. But ‘one taste’ is not a specific state, more like wetness is to all forms of water. The pickle is more exoteric than esoteric, but it shares this fractal and permeating quality.[4]Wilber, Ken, One Taste, Shambhala Press (2000), p. 315.

Finally, it matters that taste has an aesthetic orientation. At a time when most attempts to diagnose the world’s challenges appear to have an economic, epistemic or ethical emphasis, emphasising the need for qualities of taste that are not primarily cognitive seems worthwhile. The pickle is figurative, not mythical, but there is a useful parallel in James Hillman lamenting the loss of mythic understanding as a concomitant loss in the epistemic status of our capacity to relate to the world aesthetically, i.e. to be beguiled, horrified, delighted, enchanted.[5]Intellectual Deep Web, ‘James Hillman – Why Study Greek Mythology’, YouTube (2017) Learning to ‘taste the pickle’ is a training in the cultivation of epistemic taste that can be seen as an aesthetic and embodied sensibility in which ideas are tested not merely for analytical coherence or explanatory power but the beauty of their acuity and discernment in otherwise vexed problem spaces.

I am thinking here as a chess grandmaster who knows that the quality of beauty in a single move typically arises from the cascade of ideas that can only arise from a particularly refined grasp of the truth of the position as a whole.

In a different context, I remember being asked to read Schiller’s On the Aesthetic Education of Man as an undergraduate (in the late nineties) and I didn’t grasp it at all; the idea that cultivating the sentiments through aesthetic education might have tempered some of the fury of ‘The Reign of Terror’ that took hold after the French Revolution seemed obtuse to me. Now I see that it is about the importance of individuals having sovereignty over their attention, emotion and experience so that they are less likely to be engulfed by ambient hysteria, but it’s deeper than that too. Aesthetic education is also about acquiring a taste for beauty as a gateway to the fuller truths of life that temper the fervour of ideology because they seem more fundamental. In this sense the aesthetic dimension of tasting the pickle can be seen as a training in love in Iris Murdoch’s celebrated definition: ‘the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real’.

The underlying contention is that it is when we come to know and feel things in their sameness and their particularity that they really come alive for us.

Even with very complex and variegated issues like climate collapse, democratic deconsolidation, widespread economic precarity, intergenerational injustice, race relations, cultural polarisation, loneliness or depression, part of the metamodern sensibility is the inclination to feel incredulity towards seeing such problems as distinctive domains of inquiry, because they are always as polyform, co-arising and cross-pollinating. There is ultimately one predicament, but that predicament can and should be viewed in many ways from multiple perspectives. Tasting the pickle entails using the right kinds of discrimination to clarify relationships and what they imply for our individual and collective agency.

To put it plainly in today’s context:

The Covid-19 reckoning says: Reflect and contend with what really matters.

The climate emergency says: Do something! Act now!

The political and economic crisis says: Change the system! Transformation! Regenerate!

But our portfolio of meta-crises all ask: Who? How? With what sensibility and imagination?

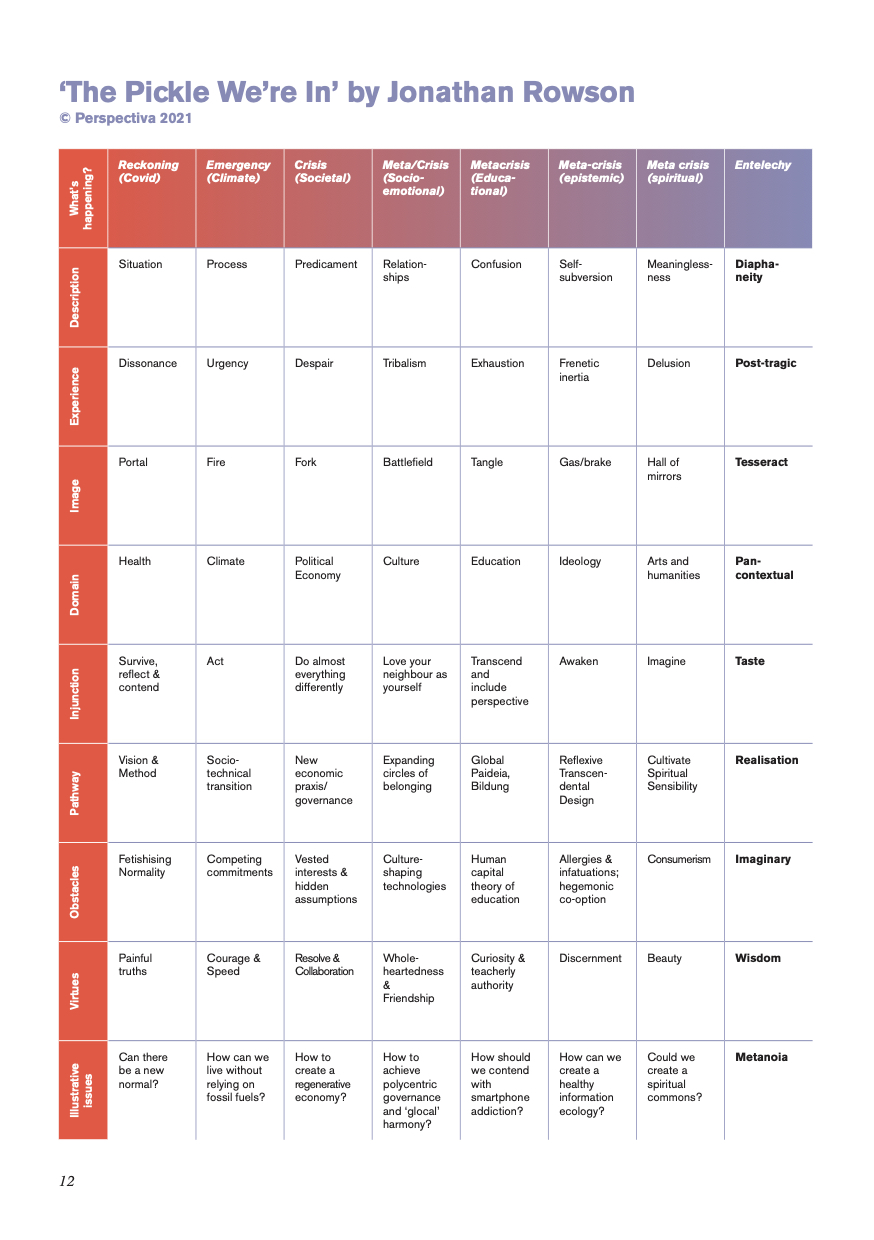

One of the worst forms of pretence is the truism that everything is connected, because it frees us of the responsibility to disclose the provenance and meaning of those connections. Mythic soothsaying is rarely as helpful as compassionate discernment. Most of the things worth fighting for are grounded in the active ingredient of at least one good distinction. For instance, as Donna Haraway puts it, although everything is connected to something, nothing is connected to everything.[6]Haraway, Donna, Staying with the Trouble, Duke University Press (2016) To really taste the pickle then, you need to taste its ingredients, to distinguish between different features of the predicament as a guide to wise perception and constructive action, all the while knowing those features also exist as one thing. It is hard to overstate the importance of this point. In a noteworthy remark in History, Guilt and Habit Owen Barfield writes of the ‘obsessive confusion between distinguishing and dividing’. For instance, we can distinguish, he says, between thinking and perceiving, but that doesn’t mean we can divide them. The table below is, forgive me, ‘my last cigarette’ as a cartological hedonist – someone who takes pleasure in maps. I am aware that it looks somewhat ridiculous, but some people like to see the ingredients on the side of a jar before they open it and taste what’s inside.[7]The table, especially the last row, includes several terms that are not introduced in the text, but act as placeholders for related terms and issues that are. Diaphaneity, for instance, is a … Continue reading

This table can be seen as the map of the pickle but not the pickle itself. The value of tasting the pickle is that while it helps to recognise the plurality and vexation of our predicament as a whole as far as possible, it is important not to get lost in it, and important to keep it connected to the beating heart of the emergency, the realpolitik of the crisis and the circumstances of our own lives. The point of ‘tasting the pickle’ then, is to put everything together with wholehearted discernment and then ask:

Have you tasted it yet? Can you feel what it means for you?

1. The Pickle is Personal: metaphor, distinctions, sensibility

In what follows I seek to establish what makes the experience of tasting the pickle personal to each of us, and then I consider how I have come to see it politically, philosophically and professionally; this overview of the pickle is a key strategic premise for Perspectiva’s work, which is why I have highlighted some of our emerging responses.

It matters that the pickle is tasted personally, that each of us struggles and succeeds in fathoming how we are implicated in what is happening at scale, even if that struggle inevitably takes place with, through and for other people; indeed, to be perennially ‘alone with others’ is a major ingredient of the pickle and sometimes its main flavour.[8]Batchelor, Stephen, Alone with Others, Grove Press (1983) But what I have in mind is more profoundly personal. While many are familiar with the maxim that ‘the personal is political’, tasting the pickle is more about grasping the subtle contention of the psychotherapist Carl Rogers: ‘What is most personal is most universal’.[9]Rogers, Carl, On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy, Mariner Books (1995), p. 83.

When we are invited to see the world through a conceptual map, we might feel some intellectual orientation but we don’t always see ourselves on it. When we are invited into the uniqueness of another’s experience and vantage point, however, our own sense of personal possibility comes alive. The more deeply and uniquely a personal experience is conveyed, the more keenly the latent possibilities of our own uniqueness are felt. Why does that matter today? In the first two decades of the 21st century we typically spoke about global collective action problems with words like ‘regeneration’, ‘transformation’ or ‘systems change’. While that kind of amorphously ambitious language does help to elevate discussions beyond narrow or naive concerns, the aspirational feels amoral, and it is insufficiently personal to have universal validity and resonance. As part of helping the reader taste the pickle, then, it feels incumbent on me to start with some personal disclosure, to help you find your own place in what follows.

I was born in 1977 and grew up in Aberdeen, Scotland in the context of the Cold War and Thatcherism. My main formative influences include becoming a type-one diabetic at the age of six and my father and brother developing schizophrenia while I was a boy; I know how it feels to be a visitor in a psychiatric hospital, certainly one of the outer circles of hell. I pretended not to notice or care too much about my parents divorcing and I sublimated all adolescent growing pains through an intense dedication to chess and later became a chess Grandmaster; that process entailed lots of travel, but much of the sightseeing was on chess boards and computer screens within hotel rooms. There were eight years in three parts of looking for an academic home in philosophy and social sciences but not really finding it, including a PhD on the concept of wisdom. There were seven years in public policy research, latterly in a polite renegade capacity where I was rethinking prevailing approaches to climate change and leading an exploration into the place of spirituality in public life. And I’ve spent the last five years as an ideas entrepreneur, building the organisation, Perspectiva, that is publishing this paper.[10]I write about all these details in considerably more depth in my book, The Moves that Matter: A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life, Bloomsbury (2019)

There has been a lot to learn and unlearn along the way, but by far the biggest intellectual influence on my life has been the experience of parenting. Apart from a few short sanity breaks masquerading as work trips, I’ve been with one or both of my sons, Kailash and Vishnu, for about 4,000 days now. I say intellectual influence not to beguile the reader with the folksy half-truth that my children are my teachers, because they are also my tormentors. Their influence on me has been intellectual in a more grounding and exoteric sense, training me to attend to quotidian matters like finding missing socks or sought-after ingredients as if they matter – though I mostly fail – and helping me to contextualise the intellect in the kinds of daily life enjoyed and endured by millions. Marriage has been another major influence, not least because on those 4,000 days of parenting I’ve coordinated activity with my wife Siva, who is a legal scholar and also has other things to think about. We both struggle to think and write while updating each other on whatever needs to be cleaned, bought, cooked, fixed, found or otherwise organised. Being busy is often lame excuse doubling as a status claim, but I am busy, so much so that I’m not always fully awake to myself as one week becomes another and I get steadily older. In his epic poem Savitri, Sri Aurobindo speaks of ‘a somnambulist whirl’, and that’s what I notice I am caught up in, especially when I have moments alone.

While waiting for the water to boil in my kitchen, I sometimes imagine myself as one of millions of passengers standing in line for coffee, travelling on a wet spaceship that twirls in a galactic trance to the tune of the sun. The cosmological setting for the plot of our lives is a geological niche too remote from human experience to be known like a particular tree or river can be known, but it is nonetheless very particular. Our planet is not merely a place that happens to be our home, but a process that gives, sustains and destroys abundant life, uncannily blessed by mathematical and mystical details that allow evolution towards language, consciousness, culture and the creation and perception of history. There may be kindred processes out there, but there is a distinct possibility we are alone; all eight billion of us. Our situation is laughable, and heartbreakingly beautiful.[11]I enjoyed the discussion between Forrest Landry and Jim Rutt on the possibility that earth might be unique in producing life like ours: The Jim Rutt Show, ‘EP31 Forrest Landry on Building our … Continue reading

God knows what we’re doing here, but there’s a real chance we might screw it all up. In fact it’s looking quite likely. The agents of political hegemony that are invested in the reproduction of the patterns of activity that cause our destructive behaviour might just be conceited and blinkered enough to destroy our only viable habitat beyond repair (The Bastards!). Alas, those who see it coming and watch it unfold might be too irresolute, disorganised and wayward to stop them (The Idiots!). The regression to societal collapse within the first half of this century is not inevitable, but it’s not an outlier either and may be the default scenario. Are we really condemned to be the idiots who blame the bastards for the world falling apart?

At times, it can feel like we really are that wayward and deluded, but there are many scholars, mystics and visionaries who see the chaos of our current world as an unfolding evolutionary process that has reached its limits of unfolding. What they see in the world today is the necessary and perhaps even providential dissolution of our existing structures of consciousness and their manifestations, including our conceptual maps, so that another way of seeing, being and living

can arise.

Something or perhaps somehow is emerging. It might be an impending disaster that looms. But our growing awareness that the first truly global civilisation is in peril is also an active ingredient in whatever is going on. Therefore, the most important action we can take – and it is a kind of action – is cultivating the requisite qualities of perception and awareness. In order for new ways of seeing ourselves and the world to arise, we need not so much to resist our current predicament, which often serves to reinforce it, but to reimagine it.

As developed further below, imagination is indispensable to help us to transgress our limitations, and while we like to think there are no limits to imagination, it is shaped and to a large extent constrained by the world as we find it. Our task, then, is to allow the intellectual premises of the process of destruction that is underway to be dismantled, which requires acute discernment about what exactly is going wrong and where precisely the scope lies for renaissance. When the intellect serves the imagination without seeking to fragment it, distinctions begin to feel like our friends.

To say societal collapse is inevitable is not shocking: it’s a truism. Societies and civilisations are mortal, and we even have reason to believe that, regardless of human activity, our planet and solar system are time-limited. The issue at stake is a matter of timing and our relationship to time, and what follows for our responsibility to attend, feel and act with a discerning sense of priority. The American writer and leadership theorist Meg Wheatley is one of few with the resolve to contend that we simply cannot effect systems change at scale in the way we keep saying we have to; there is simply too much cultural inertia and economic and political interest inside our figurative ship to turn it around in time. In the context of that hysteresis (though she doesn’t use that word), we should not expect too much from the elixir of emergence. Emergence is highly probabilistic in nature, and at present, in aggregate, most outcomes appear likely to be bad.[12]State of Emergence, ‘EP028 Meg Wheatley – Warriors Wanted: It’s Time to Defend the Human Spirit’ (2020)

Objectively, I see that, but I don’t yet feel it. I am not sure if that’s a kind of denial, or immaturity, but I feel the world is just so darn surprising that things will not unfold as we expect them to, and that there are latent immunities and antibodies that are treated like wildly optimistic unknown unknowns, but are in a sense more like viable known unknowns – nebulous intangibles that we nonetheless have sound reasons to believe in.

To make the most of whatever chance we have to protect what is most precious about life, we need to grow out of wishful thinking. We need, for instance, to get over the idea that widespread integral consciousness will forge within everyone’s hearts and minds any time soon. And yet forms of sensibility are arising that are captivated by beauty, imagination and calling, and less bound to identity and materiality, though still dependent on them too. It seems wise not to attach to specific outcomes, but I am thinking, for instance, of abundant renewable energy, wise polycentric governance, universal basic income linked to land reform, a peaceful global paideia and just enough optimal conflict in the world to keep us keen. At a species level, there are still viable and desirable ways of living to fight for, but it is not clear how we might find the heart for the scope and scale of the renaissance required to get us there.

In a geological sense, planet earth is becoming less hospitable to human life, and in an historiographical sense something epochal seems to be ending. Our intellectual function cannot fully grok what is happening, and it is far from clear what, if anything, is beginning. We can’t just make do and mend, we cannot redesign it all from scratch while we’re still here, and I don’t anticipate a mass ‘shift in consciousness’ any time soon. Still, it is clear that some beneficent forms of life are emerging, and whether they will scale in time to put out the fire or arise from the ashes is unclear. As poet W.H. Auden put it: ‘We are lived by powers we pretend to understand’.

2. The Pickle as Political Economy: Reckoning, Emergency and Crisis

The Reckoning

Like a new child in the playground who has not yet found their place, the COVID-19 pandemic has been called by many names. In the Financial Times, Arundhati Roy called it a portal between one world and the next and ‘a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves’. Writing in The Guardian, Rebecca Solnit said that in times of immense change, ‘[w]e see what’s strong, what’s weak, what’s corrupt, what matters and what doesn’t’. Writing for Emerge, Bonnitta Roy suggested we should see the pandemic as, in the terms of her title, A Tale of Two Systems: the relatively new system of global financial capitalism looking brittle, in the process of collapsing, while another system, ancient and resilient based on mutual aid and collective intelligence, was coming back into its own. Zak Stein captured this sense of burgeoning awareness evocatively in the title of another Emerge essay: A War Broke out in Heaven. There he writes: ‘Alone together, with imaginations tortured by uncertainty, we must remake ourselves as spiritual, scientific and ethical beings’.

With these influences in mind, contending with the disequilibrium caused by Covid-19 is fundamentally a reckoning to see more clearly all the entanglements we are caught up in. Poetry makes this point better than prose. Rilke said that to be free is nothing, but to become free is heavenly. That line makes sense of another by John Keats: ‘nothing ever becomes real until it is experienced’. Many events, processes and things in the world that are objectively real can only become real within us or between us when we are directly implicated in that process of becoming. On this reading, the Covid-19 pandemic means that the systemic fragility of a planetary civilisation that was already real just became real for millions of people. Our shared mortality, biological inheritance, and ecological interdependence became real. The vulnerability of our food, water and energy supplies became real. The deluded nature of plutocratic, extractive, surveillance capitalism became real. The value of care-based relationships and professions, and the solidarity of strangers became real. The need for good governance of scientific knowledge and technological innovation became real. The plausibility of a universal basic income became real. And since much of the attempt to avoid the spread of the virus is about avoiding untimely deaths, it begs the question – why are we alive at all? – thus the purpose of life as such for all of us became real. These kinds of questions arise through any critical reflection on this legal basis for capitalism, and yet they are rarely articulated as such.

The taste of the reckoning is mostly a kind of dissonance. For those whose health is not directly compromised, the pandemic is difficult precisely because day-to-day things are not that bad. It’s not a time for heroism in war or resistance under occupation. Instead, there’s a strange co-presence of normal and abnormal life.

The protracted dissonance is tiring, but I think it is possible to see dissonance as a kind of collective growing pain too, and the longer it endures, the less the desire to go back to normal will feel normal. And rightly so, because if we were in our right minds, normal would be a state of emergency.

The Emergency

Prior to Covid-19, the declaration of climate emergency by Extinction Rebellion and many political leaders was (and is) legitimate because it is grounded in an objective characterisation of our time-sensitive ecological plight.[13]Gautier, Chappelle, Rodary, Daniel, Servigne, Pablo, & Stevens, Raphael, ‘Deep Adaptation opens up a necessary conversation about the breakdown of civilisation’, Open Democracy (2020) As David Wallace Wells said at the RSA in London, ‘Everything we do in this century will be conducted in the theatre of climate change’. Urgent action of some kind is called for, but the declaration of emergency seems eerily obtuse, because it suggests we can disentangle climate collapse from the broader plight of a multifaceted and mortal civilisation, as if climate change were a deviant variable to be brought back into the fold with those purportedly benign constants called macroeconomics and politics. Alas, even during a pandemic, emissions are not falling even close to the extent that we need them to, and the idea of emergency is powerless to change that, because our problems are altogether deeper, broader and more entangled.

I like the fact that climate pronouncements have qualifications, texture and layers: the most authoritative consensus, on our best available evidence, indicates that humanity, as a whole, only has a small and diminishing amount of time, to have a fighting chance, of maintaining a viable habitat, in many places in the world, and eventually all of the world. A recent paper in Nature is one of numerous respected sources to make that kind of case, particularly in relation to the probability of tipping points that could hasten cascading collapse of ecosystems that give us the kinds of temperature, air, food and water we need for a decent quality of life, if not merely survival.[14]Lenton, Timothy M., ‘Climate tipping points – too risky to bet against’, Nature (November 2019), Vol 575, p. 592-595.

The statistical focal point that made the greatest emotional impact on me is the one that suggests our chances of even failing well are vanishingly small. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that for a two-thirds chance of limiting warming to the relatively modest constraint target of a two degrees Celsius rise in mean surface temperature since pre-industrial levels, emissions have to decline by 25 per cent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2070. But it is 2020 at the time of writing and emissions continue to rise, even in a pandemic, and show no sign of abating. Climate campaigners advise everyone to speak of the ambitious 1.5 degree target constraint, because several low-lying countries depend on that to remain above water, and it is good to establish a new norm, but it seems all but impossible given that this entails lowering our 2010 emissions levels by 45 per cent before 2030, to achieve net zero emissions around 2050.[15]McIntosh, Alastair, Riders on the Storm: The Climate Crisis and the Survival of Being, Birlinn Ltd (2020)

The idea of an emergency is useful as a call to action in the fierce urgency of NOW, because, as Rebecca Solnit notes in a Guardian essay, it signifies ‘being ejected from the familiar and urgently needing to reorient’. However, the idea of emergency is conceptually mute on what discerning action would look like, and why it’s not forthcoming. Ecologically we have knowledge, which we keep at bay through unconscious grief and terror, that we are inexorably destroying our only home. In its complexity, magnitude and consequences, climate change is an emergency unlike any we have confronted before, but it’s a collective action problem that is also laced with dissonance. Calls for action feel hollow because nobody seems quite sure how to do what we have to do. The collective challenge is therefore to attend wholeheartedly to the deeper variables in which the climate issue is entangled, and unless we do that, we have little chance of even limiting temperature rises to 3 degrees Celsius or more.[16]Less public, but uncannily similar to the climate emergency in its prospective tipping point when you begin to grasp it, is an emergency in the world of machine learning. We are in the process of … Continue reading

The Crisis

In almost every part of the world, our scope for action on the emergency is constrained not by the lack of calls for an emergency, but by a crisis – a very different phenomenon. Crisis is derived from the Greek krisis and is about the necessity for judgement in a state of suspension between worlds, characterised as a juncture or crossroads that may soon reach a turning point. To be in a critical condition, medically or otherwise, means that even if the dice might be loaded, things could yet go either way. Or more positively, as Will Davies puts it, ‘To experience a crisis is to inhabit a world that is temporarily up for grabs’.

For several decades now, there have been reductions in absolute poverty, improvements in literacy and life expectancy, and significant technological and medical progress. And yet there is also cascading ecological collapse, socially corrosive inequality and widespread governance failures, many of which relate to apparent technological successes. The simultaneous presence of progress on some metrics and collapse on others is a feature of the crisis, not a bug, because it drives concurrent narratives that obscure our sense of what’s happening and confounds consensus on how radically we should seek to change our ways.

The crisis is not that everything is going wrong but more like some things are going very well, some are going very badly, we cannot collectively decipher what this means, we need to change several things at the same time but cannot articulate the relationships to build a compelling political case to even try.[17]For further details and sources see: Rowson, Jonathan, ‘We’ve Never Had it so Good, but Everything has to Change’, The Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (2017)

Our evaluative metrics work on a piecemeal basis, saying X is doing well but Y is doing badly, but they struggle to evaluate the whole. While our intuition may be that this co-arising of positive and negative features of our planetary civilisation suggests the truth lies somewhere in between, complex systems dynamics means it is more likely that because everything is inextricably linked, that we live at a particularly unstable moment. As we look to the future, the chance of dynamic equilibrium in perpetuity is very small indeed. Civilisations are mortal, the end sometimes comes quickly, and this one may well be near the end. Even for those with an instinctive both/and mentality, it looks a lot like the world system will either evolve to a higher state of resilience, complexity and elegance, or collapse under the strain of its own contradictions.

Daniel Schmachtenberger is one of many to call this predicament ‘the hard fork hypothesis’ – the contention is that we may have to go one way or the other. I agree with the underlying sentiment about instability, but there are other possibilities, including a system that becomes more resilient and less complex, and I am not sure whether to consider the hard fork hypothesis idea axiomatic, a plausible and useful heuristic, or an article of faith. The theoretical basis for these ideas arise beyond my own competence, from bifurcation theory in mathematical modelling, Priogene’s theory of transitions in complexity in chemistry and Walerstein’s work on World System Dynamics. What I can surmise, I think, is that in the context of socio-economic systems, we do not have the kind of data that would indicate whether we are approaching a bifurcation event (as they are known) but it’s important to understand that we could be.[18]Related issues are discussed at length in an excellent interview between Daniel Schmachtenberger and Jim Rutt: The Jim Rutt Show, ‘Transcript of Episode 7 – Daniel Schmachtenberger’ … Continue reading

The design process for the kind of thinking that is discerning enough to offer an alternative to collapse is what Forrest Landry calls Transcendental Design, and that has to be a design process that is inherently reflexive because the humans undertaking it are simultaneously affected by it, because they are both constants and variables. Nobody yet knows what a viable destination will look like institutionally, nor how it will vary across the world. Some speak of this kind of approach as ‘Game B’ in which a world of non-rivalrous games is built from within ‘Game A’ – the world as we find it. Others, including Vinay Gupta, point to basic ecological and ethical constraints relating to stringent reductions in the per capita use of carbon and the ending of de facto slavery. Whatever the precise model or terminology, it seems clear that the desirable destination is less like a new place and more like a renewing and regenerative process that will include several features:

—

A relatively balanced picture of self in society, free from the alienation of excessive individualism and the coercion of collectivism, with autonomy grounded in commons resources and ecological interdependence.

—

A more refined perception of the nature of the world, in which discrete things are seen for what they have always been – evolving processes.

—

A dynamic appreciation of our minds, which are not blank slates that magically become ‘rational’ but constantly evolving living systems that are embodied, encultured, extended and deep.

—

An experience of ‘society’ that is not merely given, but willingly received or co-constructed through the interplay of evolving imaginative capacity.

—

A perspective on the purpose of life that is less about status through material success and more about the intrinsic rewards of learning, beauty and meaning.

—

An understanding of our relationship with nature that is less about extraction of resources for short-term profit and more about wise ecological stewardship (some would add, for the benefit of all beings).

—

Patterns of governance that are less about power being centralised, corrupt and unaccountable and more ‘glocal’, polycentric, transparent and responsive.

—

A relationship to technology in which we are not beholden to addictive gadgets and platforms but truly sovereign over our behaviour, and properly compensated for the use of our data. (And where, in Frankfurt’s terms, we ‘want what we want to want’.)

—

An economy designed not to create aggregate profit for the richest, but the requisite health and education required for everyone to live meaningful lives free of coercion on an ecologically sound planet.

—

A world with a rebalancing of power and resources from developed to developing worlds, and men to women, and present to future generations.

These are not necessarily the transitions that will work best, nor the only transitions that could help, but they describe the pattern of transitions we need based on our current historical sensibilities, transitions that are of sufficient scope and concern for the interconnected nature of our predicament. Many questions remain, for instance for the technological nature of the money supply or the provision, storage and transportation of energy; it is likely to mean a very different kind of world, and getting there is unlikely to be costless for everyone. Even if we seek an ‘omniconsiderate’ world of win-win scenarios and believe such a place is possible, there will certainly be winners and losers on the way there. And because there are winners and losers in parts of the necessary process of transition, and not all them can be expected to defer to the presumed wisdom of the improvement for the whole, there will be conflict, and possibly war. The world as a whole is not loyal to game theoretic assumptions about Pareto optimal outcomes, and we should not expect it to be, nor imagine that we can ever bend it with our wills to be so.

In the context of crisis and the hard fork hypothesis, political hope no longer seems to be about electing the right political parties and campaigning for a policy tweak here and there. Our ecological situation is so dire and our prospective technological changes so profound that it seems implausible that we will somehow ‘muddle through’. The critical idea to grasp this point is hysteresis – the dependence of the state of any system on its history. We are already underway, and we have been since the Industrial Revolution if not before. Things already in motion cannot be easily changed, but they can be better understood, and that understanding influences their direction. The notion that we are responding to a crisis is not therefore about a litany of problems or a general call to arms but the recognition of the need for intentional action in the context of seismic changes that will either happen to us unwittingly and unwillingly, or through us, creatively and imaginatively.

The crisis, then, is about misaligned interests, confusion over the co-arising of success and failure and the path-dependent nature of entropy and hysteresis that oblige us to change course. The emergency is the crisis in this sense: it’s not just that we have to act fast, but that we have to get it right fast, where ‘it’ is something like the underlying logic, the source code or the generator function for civilisation as a whole. That source code is not just in the world outside, but within us, between us and beyond us too. How we understand and react to our crisis is an endogenous part of our crisis and our emergency, and at a species-as-a-whole level, at a political level, at a business level, we don’t understand it very well at all.

All of our rallying cries for action and for transformation arise in cultures and psyches riddled with confusion and immunities to change. We have to better understand who and what we are, individually and collectively, in order to be able to fundamentally change how we act. That conundrum is what is now widely called the meta-crisis lying within, between and beyond the emergency and the crisis. That aspect of our predicament is socio-emotional, educational, epistemic and spiritual in nature; it is the most subtle in its effects but the roots of our problems, and the place we are most likely to find enduring political hope.

Pausing the pickle: We need to ‘go meta’ while realising we are already there

I have three main things to say about the wisdom of going meta. First, there are several meanings of meta. Second, there is epistemic skill involved in knowing when and how to go meta, and when not to. Third, we are already meta.

At its simplest, meta means after, which is why Aristotle got to metaphysics after writing about physics. It can also mean ‘with’ or ‘beyond’ but these terms can mean many things. With can mean alongside, concomitant or within. Beyond can mean transcending and including, superseding or some point in the distance. In most cases ‘meta’ serves to make some kind of implicit relationship more explicit. The ‘meta’ in ‘metamodernism’ can simply mean ‘after modernism’, but a more precise way to capture what that means is with another kind of ‘meta’: metaxy. Metaxy is about between-ness in general, and the oscillation between poles of experience in particular. Being and becoming is a metaxy, night and day is a metaxy, and modernism and postmodernism is the metaxy that characterises metamodernism; Jeremy Johnson put the point about metaxy particularly well in his feedback on this paper:

This is why I think it’s helpful to keep returning to the etymological roots, re: metaxy. Charging the word with its quicksilver, liminal nature, it approximates both the magical structure of consciousness (one point is all points), it provides a mythical image (Hermes, anyone?), it elucidates a healthy mental concept (oscillation, dialectics, paradoxical thinking), and in a back-forward archaic-integral leap, it challenges us with the processual and transparent systasis (‘from all sides’). Tasting the pickle.

One additional point on the meaning of meta is that it is invariably used as a prefix and it appears to have a chameleon nature depending on what it forms part of. The meta in metanoia is mostly beyond, as in the spiritual transformation of going beyond the current structure of the mind (nous). The meta in metamorphosis and metabolism is a kind of ‘change’, and the meta in metaphor has the composite meaning of the term because metaphor literally means ‘the bearer of meta’. The point of showing the multiple meanings of meta is not to get high on abstraction – though there is that – but to illustrate that meta need not be, and perhaps should not be, thought of principally in semantic terms as a word with its own meaning. Adding the prefix ‘meta’ introduces a shift in gear or register that can take us to several different kinds of place. It’s a manoeuvre in our language games that changes the mood and tenor of a discussion or inquiry.

As Zak Stein argues, however, there are also limits to the wisdom of going meta, which can easily become a pseudo-intelligent love of infinite regress disconnected from the pragmatic purposes of thought. Worse still, the constant availability of the meta-move creates the kind of ‘whataboutery’ that makes it difficult to create a shared world. For instance, when someone says: ‘this conversation is going nowhere’, they are going meta in a way that unilaterally ends whatever collaborative spirit of inquiry may have characterised it up to that point. To paraphrase Aristotle on anger, anyone can go meta – that is easy; what is difficult is to go meta in the right way, at the right time for the right reasons. Going meta in the wrong way can feel strenuously abstract or even absurd, but when done well, going meta should feel more like a return to sanity or a step towards freedom.

The good news is that it should not be particularly difficult to go meta in the right way because we do it all the time. Meta phenomena are more diverse and pervasive than we typically imagine – the meta world arises from our relationship with the world as sense-making and meaning-making creatures. Meta is already here with us, within us, between us, beyond us, waiting to be disclosed and appreciated. We are already meta. Learning how to learn is meta – and schools increasingly recognise the need for that. A speech about how to give a speech is meta – and people pay to hear them. Parents of young children experience meta whenever they feel tired of being tired. For a different take, if you ‘go meta’ on oranges and apples you get fruit (or seeds, or trees). If you go meta on fruit you may get to food, and if you go meta on food you may get to agriculture, and then perhaps land and climate, and then either soil and mean surface temperature, or perhaps planet and cosmos. Meta is also what happens in meditation (meta-tation!) when the mind observes itself in some way: there I go again, we think, without pausing to feel astonishment at being both observer and observed. Meta themes abound in popular culture, for instance in Seinfeld, where comedians successfully pitch for a television show in which nothing of significance ever really happened; that idea was the explicit expression of the implicit idea that made the whole series funny.[19]Liideoz, ‘Seinfeld – The Nothing Pitch’, YouTube (2010)

The meta-move is often noteworthy because it tends to happen when normal moves exhaust themselves. For this reason, ‘going meta’ is a key feature of metamodernity, characterised by our encounter with the material and spiritual exhaustion of modernity and the limitations of postmodernity. Going meta is therefore important and necessary, and it’s already a part of popular culture, so we should not fear talking about it as if it was unacceptable jargon. But we do need to be a bit clearer about why and when we use it, not least when acting in response to ‘the meta crisis’. Since I have argued that crisis has a particular meaning relating to bifurcation and time sensitivity, and we often use the terms meta and crisis to describe our predicament as a whole, the relationship between meta and crisis deserves closer attention.

Here is how I see it. The idea of the meta-crisis is pertinent and essential, and the term offers the kind of creative tension and epistemic stretch that we are called upon to experience. However, in our social change efforts we need to remember that language is psychoactive, and it matters which terms we use to attract, persuade and galvanise people. I don’t think the aim should be to stop talking about meta as if it was a secret code we had to translate to make it more palatable. Instead, I think the aim should be to disclose that what is meta is so normal and even mundane that we don’t need to draw special attention to it.

While most developmental progress is about the subject-object move, in the case of meta-phenomena, I wonder if this is an exception that proves the rule. What we appear to need is for whatever is meta in our experience and discourse to become subject again, such that it becomes a kind of second nature that we simply ‘do’ rather than reflect on or talk about. The aim is to close the observational gap by integrating what you previously exorcised by making it object, moving from unconscious, to conscious and then not back to unconscious as such, but to dispositional and tacit. In this sense, the aim is to know the meta-crisis well enough that it ceases to be ‘meta’, and ceases to be a ‘crisis’, and frees us of the need to speak in those terms. The aim is to get back to living meaningfully and purposively with reality as we find it.

Some of the most profound and promising theorising in this space comes from those who suggest we might precipitate the new forms of perception we need by understanding the provenance of our current sense of limitation more acutely. Jeremy Johnson puts it like this:

If we wish to render transparent the true extent of the meta-crisis, to get a clear sense of how to navigate through it, then we need to thoroughly identify the foundations of the world coming undone. In order to navigate this space ‘between worlds’, we need a phenomenology of consciousness that can help us to trace, as it were, the underlying ontological ‘structures’ of the old world, the constellations of sensemaking we have relied on up until now. We should do this so that we can better recognise what the new world might be like – to re-constellate ourselves around that emergent foundation.[20]Johnson, Jeremy, ‘Meta, Modern’, The Side View (2020)

I have endeavoured to try to do that in what follows. Once you take the idea of meta-crises seriously and start looking at them closely, it seems we are caught up in something oceanic in its depth and range, and plural. The idea of trying to define the meta-crisis as if it could be encapsulated as a single notion and conceptually conquered is a kind of trap. I have come to think it helps to distinguish between different features of an experience that ultimately amount to the same underlying process. In fact, that’s how I see the meta-crises writ large: they are the underlying processes causing us to gradually lose our bearings in the world.

There are many ways to parse the different qualities of meta-crisis, which are of course interrelated, but I have alighted on four main patterns, unpacked as ten illustrations.

The socio-emotional meta/crisis (meta as with/within; the crisis of ‘we’) concerns the subjective and intersubjective features of collective action problems relating to management of various kinds of commons, not least digital and ecological. In essence it’s the problem relating to the limits of compassion and projective identification, and of the world not having a discerning sense of what ‘we’ means in practical, problem-solving or world-creating terms.

The epistemic meta-crisis (meta as with/self-reference; the crisis of understanding) concerns ways of knowing that are ultimately self-defeating, underlying mechanisms that subvert their own logics. In essence it’s the problem of ideological and epistemic blind spots.

The educational metacrisis (meta as after/within and between; the crisis of education) concerns the emergent properties arising from all our major crises taken together, which entail learning needs at scale, particularly how to make sense of the first planetary civilisation; how to confer legitimacy transnationally; how to do what needs to be done ecologically; and how to clarify collectively what we’re living for without coercion.

The spiritual meta crisis (meta as beyond; the crisis of imagination) concerns the cultural inability or unwillingness to ‘go meta’ in the right way, for instance to think about the political spectrum rather than merely thinking with it, or for economic commentators to question the very idea of the economy or the nature of money. More profoundly, it is about being cut off from questions about the nature, meaning and purpose of life as a whole as legitimate terrain in our attempts to imagine a new kind of world.

3. The Philosophical Pickle: tasting ten flavours of the meta-crisis[21]Meta-crisis has a particular meaning below, but I also use it here, and above, as the default way of writing the term that captures all the different kinds of meta/crisis, metacrisis, meta-crisis, … Continue reading

Do we even know what we want? If pushed for an answer I would say I seek a world of ecological sanity that delights in its own abundance, societies with dynamic equilibriums where everyone can develop skill and taste and relationships, and forge meaningful purpose, and education that leads us to seek truth, feel moved by beauty and experience joy, but these intimations and sketches I am never quite sure what to hope for. I also feel that that desirable world is already with us to a large extent, and it would be foolish to wish it all away. There are certainly socio-economic and ecological problems to be solved, but I don’t have a working vision of Utopia as a lodestar, and doubt those who do. I notice that life is defined by processes of change that feel endemic and pervasive, that struggle is part of that process, but often a friend in disguise, and although I have no direct experience of war, widespread calls for peace on earth don’t ring altogether true; I wonder if our darkness is a feature rather than a bug, and perhaps we can only ever repress the patterns of ambitious coercion that are baked into human desire.

Whatever its woes, and there are many, the world we are called upon to love is always the one we are already living in.

What should we work towards, then, and how? It is precisely when we take this question seriously – the question of what to do about the emergency and the crisis – that the full range of meta-crises reveal themselves. What follows, then, is a performance of my own tasting of the pickle, of what it feels like to dive into the jar as it were, and play with all the elements that seem to be swirling around in the meta-crisis discourse. It is hoped that by conveying my experience of the pickle, others may think and act with an enriched set of reference points.

1. The Meta/Crisis of Cosmopolitics: We don’t have a viable We

The slash in meta/crisis signifies that the meta/crisis is almost indistinguishable from the crisis as such. The term also helps sharpen the distinction between emergency and crisis by highlighting perhaps the most fundamental feature lying within our crisis. The main limitation with the idea that we face an emergency is that there is no ‘we’ as such to address it. The We that wants to say there is an emergency is not the same We as the We that needs to hear it, and the We that needs to hear it has several different ideas about the nature of the We that should do something about it. As I argued in the second edition of Spiritualise, ‘we’ is usually an injunction in disguise.[22]Rowson, Jonathan, Spiritualise: Cultivating spirituality sensibility to address 21st century challenges (2nd edition), Perspectiva/The Royal Society of Arts (2017)

Perhaps spiritually we are One, or could be, but politically we are many, indeed for many how we decide to demarcate our ‘we’ is the fault line of politics.[23]Schmitt, Carl, The Concept of the Political, Rutgers University Press (1932)

Many believe political polarisation is the defining challenge of our time; it is certainly one of them. Fascism has been described as ‘the politics of them and us’, and while it is not a term to be used lightly, many countries are at least somewhat closer to the spirit of fascism than they have been for years. One way of looking at The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act in India for instance is that it effectively makes Hindus ‘more Indian’ than Muslims. The Indian ‘We’ may still be secular and legally plural, but politically that ideal is increasingly contested under the ethno-nationalist claims from incumbent powers that proclaim India to be a Hindu nation.

More generally, there are competing tribes, perspectives, interests and factions in the world, and perhaps there always will be. You don’t need to travel far to realise that, but I found it helps to do so. For me, spending some time in Sarajevo as part of my Open Society Fellowship was particularly useful, because it revealed how easily and tragically war can arise when a collective sense of We-ness shatters into lethal shards of them and us. At almost every level of analysis, from sclerotic global governance to quarrelling spouses, we appear to lack sanctified mechanisms to resolve what kind of We we want ourselves to be. Ecological sanity depends upon the recognition of some kind of unity in diversity, and that should not be impossible to obtain. For instance, Elinor Ostrom’s work reveals that collective action solutions are every bit as real as collective action problems.[24]Ostrom, Elinor, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions), Cambridge University Press (1991)

However, in the absence of a wholehearted commitment to something like the human rights framework or the sustainable development goals at an international macro level, or the rapid deployment of polycentric governance to coordinate meso levels, or the spread of methodologies of interpersonal micro-solidarity (e.g. micro finance) at a micro level, or a combination of all of the above, the widespread misalignment of our identities and priorities will remain problematic. Competing and incommensurate political aims undermine the stability of the kinds of cooperation and sacrifice that may be necessary for the greater good at a planetary scale in a time of emergency. That realpolitik is part of the crisis.

As Bonnitta Roy reminded me in a personal communication, while people make a lot of conceptual statements around ‘us’ as unity, the problem is that it doesn’t turn into units of action – the appropriate scale for ‘we’ as a unit of action is the critical question, and an urgent one at a time of global collective action problems where the presumptive global we is not a unit of action. I felt the acuity of this point even more profoundly in a personal exchange with Dougald Hine who noted that whenever people travel and converge for conferences of various kinds, the question invariably arises: ‘What should we do?’ And yet there is usually no ‘we’ in the room that is capable of coordinated action because they are all away from their contexts and networks where each of them may more readily establish units of action, and that recurring confusion wastes precious time.

To take an example at a larger scale, we need to keep most oil and gas reserves in the ground and virtually all coal in the ground to give us a fighting chance of staying within the relatively ambitious 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. There’s a compelling case for pursuing that global objective if you are one of the thousands of inhabitants of Tuvalu or any other low-lying small island state with non-amphibious humans who simply wish to live above water. However, if your political remit is to do something about energy poverty affecting millions of families in a coal-rich part of rural India or China, you may see things differently. Likewise if you are one of many rapidly developing African countries seeking to catch up with Western living standards and you notice that a lack of an international airport places you an economic disadvantage, it won’t look obvious that ‘we’ shouldn’t build any more airports.

The identity crisis about our ‘we’ is compounded by the confusion about our success as a we – a species. Many people feel an understandable desire to continue being ‘successful’ without really knowing what that means. One recent expression of this aspect of meta/crisis is an impressively reasoned paper in the journal Science about the lack of acuity and coherence in the idea that Green Growth or The Green New Deal, which is the policy that advocates ‘winning’ on all fronts – economically and ecologically – as the preeminent response to our plight. It would make sense if it worked, and it might even be a necessary step forward, but after reading the meticulous take-down of the assumptions behind the idea, it is hard to see how it could ever be credible as a global strategy. Let’s imagine then that a significant majority of powerful people read that paper, agreed with all of it, and decided resolutely that growth in developed countries is the wrong goal, and then acted on that post-growth understanding in a fundamental shift in policy goals and political messaging. How likely is that? Not at all likely, and that’s the crisis too – some apparent truths are deeply unacceptable politically, in the literal sense that we, writ large, are not able to accept them and sometimes also not willing to accept them, in the sense of not knowing how to do it.[25]Jackson, Tim, & Victor, Peter A., ‘Unraveling the claims for (and against) green growth’, Science (November 2019), Vol. 366, Issue 6468, p. 950-951.

No wonder people will continue to ask: What should I do? What can I do? If we don’t really know who they are (and often they don’t really know either) all we can offer are lowest-common-denominator things we don’t wholeheartedly believe in anymore.

Recycling is good, but feels lame when your country is on fire, and writing to your elected representative feels quaint when their leaders brazenly lie. And climate activists rightly remind us that we are running out of time, so there is no time to waste.

Perhaps we save time by reminding ourselves that the question, what should I do, is always asked by particular, knowable, historic, geographic, embodied, learning individuals. The answer can and should therefore be unique to their pattern of character formation, their professional skill, social influence and growth potential; and it usually comes down to this: do what you are best at to address whatever is most generatively helpful, and collaborate with other individuating people. A deeper exploration of individuation as a mostly Jungian concept traversing psyche and character and journey is beyond our scope, but in terms of its implication for action it is closely related to the achievement of autonomy, and the best short definition of autonomy is an open system that is capable of closing itself. That, in essence, may be what we need at scale – open systems capable of closing themselves. The ‘We’ required to collaborate for the greater global good depends on individual capacities and sensibilities that are not just insufficiently abundant, but insufficiently autonomous because they are also, as Carl Rogers mentioned earlier, insufficiently personal. So when one of the eight billion asks us then: What should I do? At least part of the answer has to be: You tell me.

At a time when requisite action – on consumerism, on smartphone addiction, on political polarisation – is often a kind of restraint, one of the psychological variables we need to understand is the provenance of agency, because that determines the extent to which an action is volitional or habitual, chosen or coerced.

One of the reasons the collective action problems of our time seem overwhelming therefore is that we sense that they are actually problems of collective individuation in disguise.

There is a necessary realisation waiting for all of us that yes, we are utterly contingent and interdependent, but we are also uniquely relevant and ethically singular. While the kind of We that might actually be fit for purpose cannot be wished into existence then, it can perhaps be forged. That forging process, an educational process, is a collective effort to allow all the Is that we are to begin to know, find and create themselves through a collaborative institutional and cultural effort that speaks to that endeavour. Technology alone will not save us from the sensibilities that lead to the misuse of technology. What we need to mitigate ecological collapse, cultural fragmentation and political and economic breakdown is the widespread internalisation of a global commons, such that people feel their individual actions are a palpable part of a global web of life. Getting to that kind of collective sensibility will not happen if your raw ingredients are eight billion or so pieces of generic collaborative fodder. There is no such ‘We’ to be mobilised, and we know it. Cooperation at scale may nonetheless be possible but we should consider what follows if it depends on the resolute, discerning and skilled collaboration of individuals worthy of the name.

This challenge of collective individuation applies across contexts, and in the context of his relationship to Buddhism, Stephen Batchelor puts the underlying aim as follows:

The Dharma needs to be individuated in the Jungian sense, meaning differentiating yourself from the collective, from archetypes, from the norms or traditions, and so forth, in such a way that you become increasingly your own person. That doesn’t mean you become an egoist, but it means that you’ve teased out your potential in such a way that you can optimally flourish to be the person that you aspire to be, that may have elements of Buddhism or Christianity or socialism or whatever fed into it. The mix is uniquely your own. It’s your own voice that you find. That, to me, would be a vision of where we’re going.[26]Stephen Batchelor on the ageless practice of self-reflection: Bachelor, Stephen, ‘Solitude Will Change Your Life: How to Be Alone With Others’, Psychology Today (September 2020)

The majority of the world’s population may remain highly suggestible, and susceptible to manipulation by plutocratic alchemists who stoke base impulses and appetites and turn them into figurative gold for private gain. A critical mass, however, can become relatively discerning and act according to their own judgement, ideally with some care for the greater good and capacity to help others find their own unique contribution. I reflect further on the idea of collective individuation in forthcoming publications. For now, it is sufficient to understand that the individual and the collective are profoundly co-constituted, and our predicament calls for a planetary-scale response that is both profoundly collective and deeply personal. This ‘We’ challenge of collective individuation is at the heart of the new strategy for Perspectiva’s Emerge project.

2. Metacrisis in World System Dynamics: we’re not good at joining the dots

The composite word ‘metacrisis’ is inspired by our German friends, and is useful for resolving to speak to the cross-pollinating crises of our time as one whole thing. Here the aim is to better ‘join the dots’ between apparently disparate phenomena while recognising, as Gödel helped us discern, that no single grand vision or narrative, however textured and inclusive, can fully make sense of itself. The simplest view of the metacrisis then, is that it’s about whatever underlying crisis is driving a multitude of crises, not just ecological collapse (which is certainly bad enough) but also a range of governance and security issues, alongside global economic instability and inequality within countries, a steep rise in mental health problems and a decline in social trust. It’s as if we have a civilisation-level wicked problem.

This idea of an underlying problem behind, within and between all problems goes back at least to the 1970 Club of Rome report that describes 49 ‘continuous critical problems’ which they also call ‘meta-problems’.[27]The Club of Rome, ‘The Predicament of Mankind: Quest for Structured Responses to Growing World-wide Complexities and Uncertainties – A Proposal’, Accessed via Demosophia.com (originally … Continue reading More recently, in a talk at Google, the philosopher and entrepreneur Terry Patten reflected on the need to speak to meta-crisis as ‘the sum of our ecological, economic, social, cultural, and political emergencies’.[28]Talks at Google, ‘Confronting The Meta-Crisis: Criteria for Turning The Titanic – Terry Patten’, YouTube (2019) More recently, when the first Covid-19 lockdown began, Elizabeth Debold argued in our first Emerge online gathering that one collateral benefit of the reckoning was that many thousands of those who were just beginning to think systemically (a non-trivial cognitive achievement) would have accelerated their development. As the nature of the world’s interdependence and the reality of the relationship between apparently different ‘things’ became palpable, so did a growing awareness of the metacrisis. This way of seeing the metacrisis – as a descriptor for the pattern that connects various crises – is perhaps the most conventional use of the term, and it is the premise for Perspectiva’s encapsulation of the scope of our inquiry as ‘systems, souls and society’.

3. Metacrisis in Historiography: Modernity and postmodernity struggle to procreate

The composite metacrisis can also be seen as the failure of culture to evolve quickly enough to save itself from itself.

Cultures vary enormously of course, and different kinds of changes are called for in different parts of the world, but the active ingredient in question here is shared across cultures, and called by various names: cultural code, hidden curriculum, consensus reality, paradigm, collective imaginary, value memes, shared story, sacred canopy, social surround. All of these terms mean something a little different, and sometimes they apply to particular places and at other times to the world as a whole, but they all refer to the prevailing pattern of norms and forms of life and the assumptions they entail; at its most abstract and generic we can think of it as a semiotic fabric that acts as an ideational ozone layer for humanity. When the late anthropologist Clifford Geertz said that we are creatures suspended in webs of meaning that we ourselves have spun, he was referring to something like this.

This metacrisis is mostly a metacrisis of modernism – the world of the presumed universality and beneficence of science and reason and progress – and the battle that we have not yet fought and won to transcend and include that presumption. Many, including Jürgen Habermas, appear to view postmodernity as a phase within the modern historiographical epoch in which the critical tools of modernity were turned back on itself. While the postmodern critical inflexion has value and is necessary, in terms of cultural renewal and adaptation, it also appears to be a kind of dead end.

Post and meta can both mean ‘after’, but while the after in postmodernism is more like modernity’s after party – a continuation of the same party, or ‘afternoon’ – a later stage of the same day, ‘meta’ has a notion of after that is more than mere temporal extension. Meta here signals that a qualitatively different kind of relationship has arisen. When meta is placed in this context, and understood in this way, the cultural meta-crisis is about our apparent failure to cultivate metamodern sensibilities with sufficient permeation at scale to adapt to our historiographical epoch of metamodernity. This qualitatively new epoch has been with us to some extent since the birth of digitisation, and its impact on the lifeworld has arisen alongside the apparent spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity. We all know from abundant misquotations of Einstein that cultural and moral progress needs to keep pace with technological and economic developments, but that’s not happening.

Viewing the metacrisis in this way helps illuminate why metamodernism as a normative endeavour matters, as I feel Greg Dember puts mostly acutely in his essay for the Side View (spring 2020: ‘What is Metamodernism and Why Does it Matter?’) when he argues that we need it to protect our interiority from capture on either side of the oscillation of the dominant cultural codes. Each of us risks losing the meaning of our lives to either the scientific reductionism and instrumentality of modernism or the identity politics and irony of postmodernism.

The primary function of metamodernism may therefore be to safeguard interiority.

Curiously, and perhaps excitingly, the resources for that task are as likely to be found in indigenous and pre-modern cultures as in untethered futurism, and that may simply be because we need to rediscover our place in nature, and patterns of activity and meaning that fall out of that.[29]Perspectiva, ‘What is Metamodernism?’, YouTube (2020)