Anthea Lawson

Oct 26th, 2020

Can we talk about where stories come from?

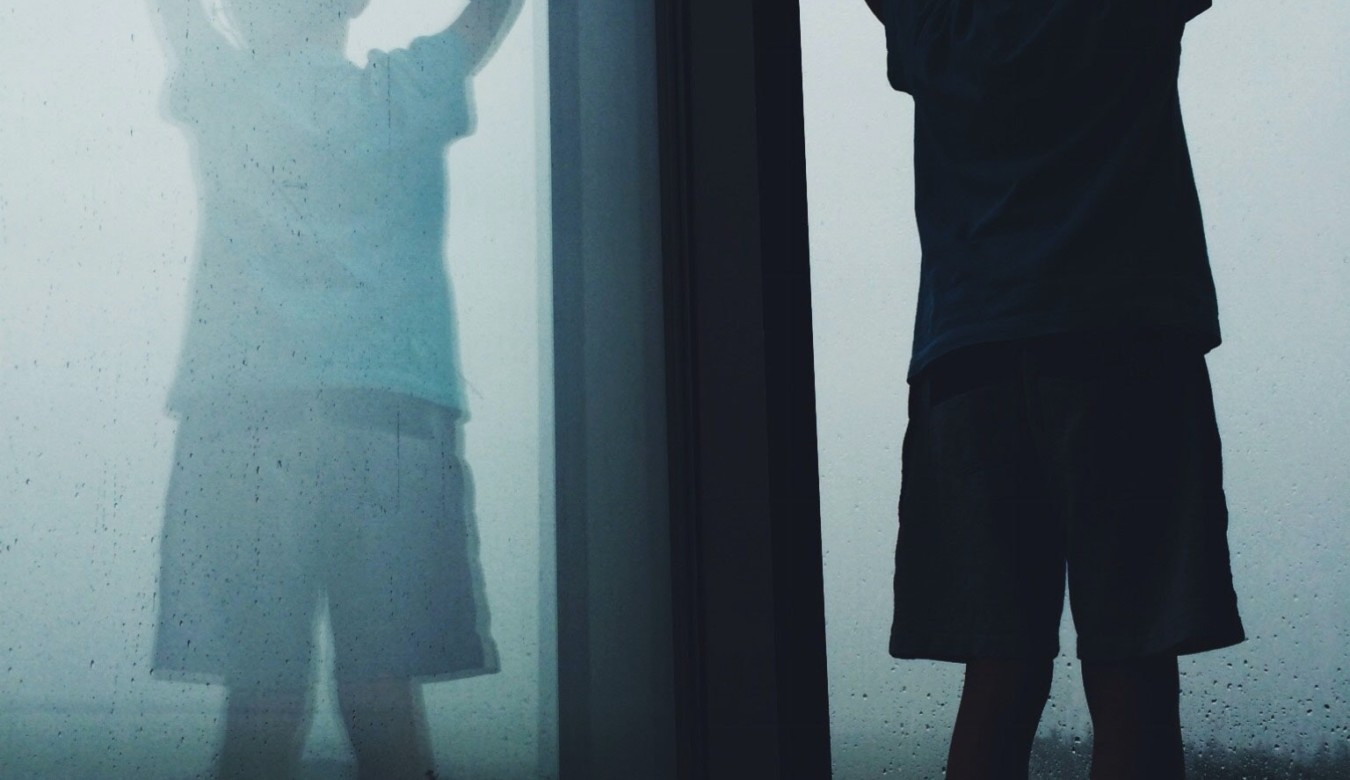

I think some of them emerge from the dark. The stories that drive us most powerfully were born in the shadows of what we don’t remember. And the strongest story of all may be the one that tells us whether we are alone, or part of something bigger.

It turns out that the way we look after babies can give them, as adults, a worldview that they won’t even know they have. That take on the world has huge political consequences. And our own take on the world, which we might like to think of as a political ‘choice’, may have origins in our infancy.

We learn our stories at our parents’ knees, but we don’t just learn the stories they tell us. We also learn the stories they show us, by how they are with us. These stories about our vulnerability, even more implicit than the messages of the old fairy tales, are the earliest ones we absorb in the unremembering dark of our first months and years. Because of this, they shape, very powerfully, the way our brains work and the way we understand and react to the world.

I’ve come to this through being a campaigner and a parent, which I used to think, as I rushed from one to the other, were entirely separate activities. Now I’m not so sure. Understanding the implications of attachment theory (which, as I’ll get to later, is not exactly the same thing as attachment parenting) goes way beyond making me question how I am with my children. It’s about what might lie at the deep roots of progressive change.

For more than a decade I did the sort of campaigning that involves investigations, report-writing, meeting bureaucrats, arguing with companies and their shills, suggesting new laws and trying to find politicians who will support them. To do so I used my journalism skills to find and tell stories that were full of facts. I put together impressive, towering edifices of carefully sourced facts about what was wrong, hoping that their weight would persuade their recipients ineluctably to change course.

The first few years I was working towards controls on the arms trade before moving, I thought, away from fighting a symptom and closer to the cause of the problem: economic injustice. I tried to communicate how poverty is constructed and not inevitable. I investigated and ranted about the role of banks and tax havens in making and keeping people poor. With our facts we made this a bigger issue that more people knew about, and achieved some small changes to the financial regulations.

Well, that seemed worth doing, and I could tell my organisation’s funders that we had achieved what we set out to do and they could give us more money to carry on. This was our way of bearing witness to the social, political and environmental damage caused by our economic system. People are doing so, in their own communities, at the doors of big business and in the halls of power, against all odds, every day. Joanna Macy calls it ‘holding actions’. The organisation I worked for called it ‘getting the bastards.’ This work doesn’t go away.

But I was having a crisis, both tactical and existential. Like so many campaigners I was still presenting my ‘opponents’ with facts and expecting them to take action, when everything that’s known about values and politics tells us that people will reject any facts that threaten the values they hold at the core of their identity (as the events of 2016 have now made punishingly clear). And more fundamentally, it no longer felt enough to be trying to temper the worst excesses of a system so inherently destructive. Even if I achieved all the changes listed in my ‘campaign strategy’, we would still have a financial system whose growth requirements would not cease until there was no nature left.

Accustomed to finding the strategic pressure point where my intervention might have most effect, I tried to identify the place of root cause where it might be best to work. But there isn’t such a point — at least, not one that is amenable to the campaign techniques I’d been using. Greed? Growth? Yes, there are good arguments to be made about how a non-growth, steady state economy could function, and some people are doing that, and others are getting on with it locally. All of which is exciting. But in the mode I was used to working in, that would still mean persuading the same people so powerfully vested in the current system to change course. Meanwhile we are in the middle of the sixth mass extinction in the earth’s history, this one caused by us: I often cry when I think about this.

I continued excavating and reached some of the founding myths of our culture. Stories about progress, stories about competition, stories about our separation from each other and from the matrix of life that supports us.

There’s no fundraising or campaign plan here. My support — and to be clear, it was my soul that needed support, looking into this abyss — came from the voices of others who were already thinking about the failure of these myths and the need for new ones. From Paul Kingsnorth and Dougald Hine, who had reached a similar point with campaigning when they launched Dark Mountain in 2010. Looking out into the dark as their publications do is terrifying, but brings strange liberation. From Charles Eisenstein, who writes compellingly and hopefully about the beginnings of a new story of what he calls ‘interbeing’ to replace our old story of separation, who asks us, instead of demonising those we’d seek to change, to ‘enter the question that defines compassion: What is it like to be you?’ From Joanna Macy, who talks about the profound shift in consciousness, in our perception of reality, that must accompany any practical action in the world (the Transition movement calls this ‘inner transition’).

Perspectiva, a new think-tank, is doing its thinking at the junction of these roads. It wants to change the paradigm rather than just change the system or the policies within it. It recognises that our inner worlds have an effect on the outer world we create. If our economic system — in its current particular manifestation of neoliberalism that turns every human need into a market opportunity where somebody else can profit — is the system that needs changing, then an important aspect of the paradigm in which it exists is our story of ourselves as unconnected competitive individuals, to a degree probably unprecedented in human history. At its extreme, that paradigm frames not just an economic system whose costs are too high, but a view of politics — hello, Donald Trump — grounded in division and fear.

And so the paradigm change we might seek is for many more people to understand, fully, that we are not alone. It sounds like a new story, compared to what we’re used to, but of course it is very old. We are connected, to each other and to the natural world in which we evolved, in profound ways, and life is better — indeed, it will only be possible — if we create stories to live by which honour that. There is plenty in ecology and systems theory to make this clear, all of which can help with intellectual understanding. But it’s more important to feel it, since it’s our emotions and underlying values that dictate so much of our behaviour.

And whether we can feel it depends on what happens in our infancy. It’s as babies that we learn whether we are alone or not. Whether it is ok to be vulnerable, or whether we need to put on a hard shell and try to look after ourselves. What empathy with our vulnerability feels like, and therefore how we can show empathy to others who may be vulnerable. Whether the world is somewhere that our needs get met through cooperation, or a place where we are alone and so must rely on ourselves and need to be fearful. And this all happens before the age of three. We learn it, implicitly, from the way that our caregivers respond to our enormous, non-negotiable infant needs.

It comes down to attachment theory, which has been increasingly understood since the 1950s and 60s when the psychologists John Bowlby and then Mary Ainsworth showed that children’s very early experiences of ‘attachment’ to their primary caregiver (usually their mother) were the key to their emotional development. Research has continued since, and there’s now a substantial body of evidence showing that if the care you receive as an infant — while the brain is still growing and making its connections — is unresponsive or erratic, your emotional thermostat is going to be set to be more reactive, and you will be more insecure.

The psychotherapist Sue Gerhardt made an excellent summary in her 2004 book Why Love Matters. What infants have evolved to expect is a response when they cry, since for most of human history, no response meant becoming lunch. As they receive a loving response which calms them and attends to their physical and emotional need, babies are protected from unmanageable distress and slowly start to develop a sense of themselves existing in the world; of themselves as a self who has agency and influence to make things happen. A response means that their feelings are valid and have meaning. As Gerhardt says, ‘his dependence on others is a positive experience. The world will seem a benign place and he will expect it to continue that way.’ It’s ok to be vulnerable, since our connection with others will support us.

If babies don’t receive regular prompt and loving responses, then they will develop with a weaker sense of self, and a greater tendency to fear. Why might this happen? Because their caregiver is depressed, or busy with other children. Or believes as many people still do that to respond to babies’ needs will spoil them and turn them into a tyrant. Or because they are following a child rearing approach that emphasises getting the baby on a fixed schedule for feeds and sleeps, even if it means repeatedly not responding to their cries. Or — according to some psychologists, and this is difficult, as some parents have little alternative — because they are in a nursery while still very young, competing with other needy babies for the attention of the staff.

The lesson is ‘that they must subordinate their will to the more powerful people around them. Taught that comfort cannot be relied upon, and left to manage their distress alone, this can constitute an early but devastating life lesson,’ says Gerhardt.

In her practice she says it is ‘rare to find people who are aware of the importance of pre-verbal relationships, or of the powerful cultural messages that can be inadvertently conveyed to babies.’ Most adults ‘are well aware that a baby can’t change his own nappy or regulate his own basic bodily processes without help, but we are perhaps less clear about the fact that a baby can’t soothe his own feelings or manage his own mind.’

The cultural messages here can be strong. ‘They’re as tough as boots,’ I was told when my daughter was tiny. ‘Put her down in the basket,’ when she was crying. ‘She’s manipulating you,’ when the crying stopped and I was rewarded with a huge smile on picking her up. Advice like this doesn’t come from lack of love, but from habit. My instinct was to do the opposite. My desire to understand that instinct, and why I was being told something different, led me to the literature on attachment, which I’d never encountered before I had a child. The research supported my instinct: that babies who were responded to promptly did not become more needy, but quite the opposite — they cried less, and so were easier to look after.

The pervasive story that babies will be spoiled if you respond to them too much, that they are ‘manipulating’ their parents to get attention and we must resist this, has passed down the generations through enough families that there is a critical mass of people who do not feel secure. Research in the US and Europe suggests 40% of the population is not securely attached, and the strongest predictor for being insecurely attached is having a parent who is not securely attached themselves. The psychologist Oliver James describes this dynamic in his book How Not to F*** Them Up.

Mothers who were responded to enough in their own infancy are likely to do so automatically with their own children. Mothers who were not will do one of two things. Either their infant’s vulnerability will make them feel uncomfortable and they will seek to keep its reminder of their own unmet needs and ongoing vulnerability at arms length by using sleeping and feeding routines to reduce their baby’s demands on them. Or they will seek to compensate for the lack they experienced by holding their baby close. It is possible to avoid Larkin’s outcome… but without awareness, it is also very easy to hand insecurity down the generations.

Our parenting doesn’t just have consequences for individuals, but for society. One set of consequences of insecure attachment concerns the greater risk of behaviour problems, poorer language development and reduced resilience to poverty, family instability and parental stress and depression. These are well summarised in a Sutton Trust report, Baby Bonds. I want to focus, though, on the perhaps more intangible impacts. Part of it is that despite our immense material wealth and comfort in industrialised countries, we continue to behave as if deprived and in competition with others to obtain ever more things. Material abundance is not the same as emotional abundance, and there is a critical mass of people lacking a sense of emotional abundance from their childhood, even before advertising spreads its poison. So this is part of the story of overconsumption: our insecurity leads us to trample too heavily on the world.

Another consequence concerns how we treat others; how we react to their vulnerability. How susceptible we are to political narratives that are, at their core, about fear.

The ability to recognise that other people have minds and feelings of their own and may experience things very differently to ourselves is called ‘mentalisation’. To do this you need to be open to your own experience. If you can’t tolerate, let alone fully experience your own emotions, you cannot be open to other people’s emotions. And if as an infant you did not experience help in being soothed and recognising your own emotions, you may not be able to tolerate your own emotions as an adult. Your own vulnerability may become an insensitivity to the vulnerability in others, a attraction to rightwing politics that cut the safety net everyone needs when they are vulnerable through being a child, a woman producing children, somebody with a disability, somebody who is old, somebody who can’t find a job because the economy is all wrong. Your insecurity may also become fear, a lack of tolerance of others, and an attraction to authoritarian leaders who promise safety.

George Lakoff, a professor of cognitive linguistics at Berkeley, uses the terms Nurturant Parent and Strict Father for two models of the family which give rise to different moral world views and unconscious frameworks that underpin people’s thinking — including how they understand politics. In thinking about how a nation should be governed, he says, we have learnt our primary experiences of governing in the family.

The Nurturant Parent encourages a democratic family, in which parents explain decisions to children, using concepts of respect and compassion rather than fear of punishment to achieve discipline. Children become self-disciplined and self-reliant through being cared for and having their needs for loving interaction met. In a Strict family the father is in charge of his wife and children, providing for and protecting the home and using punishment to enforce discipline which is for the children’s own good. Kids mustn’t be coddled for fear of spoiling them which will keep them dependent; they need to be toughened up to face a competitive world. If they learn self-discipline at home, they will be moral.

And so in the powerful metaphor of the nation state as family, used on both sides of the US cultural and political divide, Nurturant Parents are more likely to be progressives, Strict Fathers more likely to be conservatives. For the Strict, being dependent on the government is immoral as you obviously haven’t learned to be self-reliant from your family. In his books Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know that Liberals Don’t and Don’t Think of an Elephant, Lakoff shows how the very particular positions held by conservatives in the US — which taken together might seem, to a different mindset, illogical: anti-abortion but pro-death penalty; against government social spending but pro-military spending — emerge from the same root metaphor of the nation as family. So social spending encourages people not to be responsible or independent and is morally wrong, but military spending is about projecting authority and discipline, which is good. He was writing about the rise of Trump from this perspective on his blog throughout 2016.

A researcher at the University of Massachusetts called Matthew MacWilliams carried out a survey in January 2016 showing that the strongest predictor of support for Trump — greater than education, income, gender, age and religion — was authoritarianism (what Lakoff would call the Strict outlook). And the best way to measure authoritarianism? You ask four questions about childrearing that indicate how people prioritise order and hierarchy. Is it more important to have a child who is respectful or independent; obedient or self-reliant; well-behaved or considerate; well mannered or curious? Those who choose the first option of each are considered strongly authoritarian.

Writing in Politico, MacWilliams commented, ‘We’ve understood authoritarianism since the Nazis. While its causes are still debated, the political behaviour of authoritarians is not. Authoritarians value safety, and are motivated by fear. They obey authority and are drawn to it. They like strong leaders. They are fearful of outsiders and respond aggressively to them if threatened.’

The psychologist Alice Miller, who died in 2010, argued not only that who Hitler became is explicable from his brutal childhood, but that the reason so many Germans were susceptible to him was because they had been conditioned by their abusive childhoods to accept a harsh father. Turn of the century German parenting advice advocated authoritarian approaches including hitting babies to stop them crying, using threatening looks and gestures once they had learned that lesson, and refusing them food that a parent was eating in order to teach self-denial.

Miller was careful not to suggest parenting was the only cause of something so monstrous and complex as the Holocaust, but couldn’t accept that the anti-Semitism which had already existed in Germany before Hitler’s rise only needed the economic privations of the 1920s and 1930s to be jolted into mass participation in genocide. It required something which had cauterised the capacity for empathy in so many participants: in her view, their brutal childhoods. Conversely, Miller also tracked down a study of individuals who had risked their lives to help Jews, which found that the only factor separating the rescuers from perpetrators and the passive was they way they had been brought up. Their parents had used argument rather than punishment to discipline them, and they were rarely hit.

Lakoff’s discussion of parenting doesn’t focus specifically on infancy. But he makes a telling comment in his acknowledgement at the start of Moral Politics: ‘This book began with a conversation in my garden several years ago with my friend the late Paul Baum. I asked Paul if he could think of a single question, the answer to which would be the best indicator of liberal vs. conservative political attitudes. His response: ‘If your baby cries at night, do you pick him up?’ The attempt to understand his answer led to this book.’ Lakoff is talking here about how attitudes to parenting and attitudes to politics go together in the same unexamined mental framework, and is not commenting explicitly on what might happen to the political views of the people who didn’t get a response when they cried at night as babies. But others go closer.

Suzanne Zeedyk, a psychologist who blogs regularly about the impact of our attachment needs, makes the explicit point that if we don’t get the sense of safety we need as infants because of misguided (even if well-meaning) parenting approaches, we will keep on seeking it. So political choices become determined by attachment needs that persist into adulthood. And what Trump is offering is a sense of safety:

‘Our experiences as babies and toddlers lay down neural pathways in our brains that determine how risky the world seems’.

Those pathways are obstinately robust… If the environment often feels scary to you as a baby…your brain and body become wired with enough fear sensors to keep you trapped within the physiological emotional framework your brain set up as an infant. Your brain sees no reason to question that framework .Why question reality?’ Trump, she says, ‘is dangerous because he legitimises fear. Leftover baby fears are oh so powerful, lurking in the dark of our neural pathways. That’s the point of attachment theory.’

Talking about the Nazis is one way to add rocket fuel to awkward school gate discussions about whether to leave a baby to cry at night. Creating authoritarian followers is one kind of risk — one that feels scarily real in the age of Trump. Producing people who are less capable of empathy, stuck in stories about how separate we are from each other, and who fill the gap with consumption just as our civilisation reaches its greatest crises is another. What are we to do with such information?

I think it gives us choices. Our hugely improved understanding of brain development and attachment gives us a better basis to make decisions about how to care for babies. So much of how we respond to our children is conditioned by unexamined repetition of how we were parented ourselves, making us just another link in the intergenerational transmission of insecurity. Understanding how attachment works gives us a chance to recognise what holds us, step outside it and say, stop, this goes no further — although we are likely to need support and help in unpicking our instinctive reactions. It might be a sounder basis than the search for alternatives from books that can feel, standing in front of the parenting advice shelf, like a neutral and value-free expression of consumer preference: ‘my friend says I should go for Gina Ford, but my sister likes the Baby Whisperer…’

Parents who want to increase their responsiveness to their babies may be attracted to the current vogue for ‘attachment parenting’, which encourages mothers to breastfeed whenever the baby wants, carry him in a sling on her body, and share her bed with him. It sounds like it could be the practical implementation method for attachment theory, but while the theory is well documented, the claims for the parenting method have not to my knowledge been rigorously tested. But they do make instinctive sense, and chime with what observers of childrearing methods in tribal communities have long noticed (most influentially in Jean Liedloff’s 1975 book The Continuum Concept): that babies are held much more, and cry much less, than we are used to in industrialised societies.

Extended breastfeeding, carrying and co-sleeping are fantastic for babies but they may not be possible all the time. If you’re desperately depleted after a traumatic birth you may not be able to produce enough milk to exclusively breastfeed. If your pelvic floor muscles are trashed, physios will tell you not to carry a heavy baby in a sling all day long. And if your child sleeps like a wriggly starfish with razor toenails you may not want her in your bed. None of this stops fierce judgment on attachment parenting forums of those not doing it, and vice versa, in the latest episode of the tiresome mummy wars.

I think the rows are a distraction. Firstly, because while all these things are lovely and do work, you can create a secure attachment bond with your child even if you can’t do all three of them, by being aware that good attachment is created primarily through loving responsiveness. Secondly, because attachment parenting seems to throw all the responsibility onto individual parents — and usually, more to the point, the mother.

It turns into parents bashing each other for their choices in order to make themselves feel better, when actually we should be looking at the structural circumstances we find ourselves in and directing our attention — and rage — out at them. The ancient practices on the attachment parenting tick-list don’t make much sense if you’re trying to do them all on your own. Constant breast-feeding and baby-carrying is very hard if you’re caring for older children with no help. Sleeping with a baby in your bed who wants to feed every hour, all night, every night, doesn’t work if you haven’t got a tribe to hold the baby during the day so you can get some actual, you know, sleep. Trying to emulate hunter-gatherer ways without other hunter-gatherers around you to help is, in short, hard.

Even minus the ‘attachment parenting’ confusion, attachment theory can feel like another stick for parents to beat themselves with when we should be looking wider. If you’ve had post-natal depression, sent your child to nursery very young, or if you’ve become so unable to function at work from lack of sleep that you’ve resorted to ‘sleep-training’ your baby (which usually involves some form of leaving them to cry), it can be awful to contemplate that this might have negatively affected your child. But post-natal depression is often, in industrialised countries, a consequence of isolation and lack of support. Many families need both parents working in order to pay the bills and nursery may be the only practical childcare option. And while some sleep-train their babies very young because they mistakenly believe that it’s a reasonable expectation for new babies to sleep on their own through the night, many parents — I am among them — resort to it at some point because they can no longer cope at work, or looking after children all day on their own, on so ridiculously little sleep.

The real problem is that we’re trying to do this on our own. It’s nuts to be stuck in a dwelling place with a small baby and no company when you haven’t even recovered from birth — and it’s still nuts when the baby has become a small child, or if you’re a father doing the care. We didn’t evolve to do it like this. In fact, as the sociobiologist and evolutionary theorist Sarah Blaffer Hardy points out in her excellent book Mothers and Others: The Evolutionary Origins of Mutual Understanding, we wouldn’t have evolved to this point at all if we hadn’t been engaged in what primatologists call ‘cooperative breeding’, with help in childcare from ‘alloparents’ in the same community. It’s simply not possible for a hunter-gatherer couple to find all of the calories their offspring need before reaching independent adulthood.

The urge to cooperate and to share was wired into us over many tens of thousands of years.

Gerhardt thinks it’s extraordinary that despite all of the funding that has gone into attachment research, so little of it has percolated into public consciousness let alone policy. She quotes Meredith Small, a professor of anthropology at Cornell University who has studied child-rearing around the world: ‘It is ironic that while research on the critical role of attachment relationships for healthy infant development emanated from the West, Westerners alone do not put this research into practice.’

I think it’s more than an irony; there may be specific reasons why we might not want to acknowledge the full implications of attachment theory. There’s something awfully unfeminist-sounding about suggesting that women have to spend ages with their babies. Attachment theory emerged at the same time as second-wave feminism, and feminists didn’t like what sounded like biological determinism just when they were trying to reject patriarchal oppression which relied on it. An infant attached was a mother enchained. They particularly didn’t like Bowlby’s view that mothers should not go out to work, and protested when Cambridge University gave him an honorary degree in 1977. Furthermore, to get into mother-blaming for a child’s outcome is unfair as a mother is subject to her social context, her other relationships, and all the intergenerational transmission of mothering that she has received from her forbears.

As Susie Orbach reflected in 1999: ‘To talk of what children needed from mothers without understanding the social position of women was, from a feminist perspective, to miss the point.’

In rejecting attachment theory entirely, however, feminists threw the baby and her attachment needs out with the patriarchal bathwater. Hrdy provides a thoughtful discussion of this in her book Mother Nature: Natural Selection and the Female of the Species. She describes her fury as a student at the patriarchal assumptions of the evolution researchers who taught her, the way they ignored the selection pressures that operated on women through their varied mothering strategies. So it was understandable, she says that feminists constructed ‘alternative origin stories, their own versions of wishful thinking about socially constructed men and women, and infants born with more nearly a desire for mothers than a need. Mother love could safely be interpreted then as a ‘gift’ consciously bestowed’.

But Bowlby’s insights are as irrefutable as the babies’ needs he identified. Where he was wrong, Hrdy says, was in his assumption that it was mothers who had to do all of the caring. Babies can form sound attachments to other close figures too. With her deep evolutionary perspective, she says: ‘there is little doubt that over the last million years or so, infants have always striven to remain in continuous contact with their mothers for at least the first few years of life. This was the infant’s first choice, but living up to this ‘Pleistocene ideal’ of mothering may have been tough for a mother to do — even in the Pleistocene… This preferred scenario is not the only one mothers employed. Wherever reasonably safe alloparental options were available, human mothers made use of them, as many mothers in foraging societies in Central Africa and South America still do.. Alloparents were more important alternatives to continuous one-on-one contact with the mother than Bowlby had realised.’

More practically for current mothers who leave their babies to work, Oliver James reassures them that this is ok as long as they recognise the importance of choosing somebody else who can respond in the same one to one way. Nurseries, show the research he summarises, are the least good option, at the end of the list after fathers, grandparents, nannies and then childminders.

The traditionalist response to any suggestion that children might be suffering from our current work regime is to send mothers straight back home. The left, meanwhile, avoids talking about feelings to focus on employment and childcare policies from the perspective of gender equality and contribution to the economy. Neither is a wide enough perspective. We’re obviously not going to step backwards and sacrifice women again, but now we’re risking sacrificing babies’ and children’s needs — and the possibility of a more empathetic society.

The answer, which comes both from psychologists and feminists, and is being put into practice by increasing numbers of fathers (Gaby Hinsliff’s book Half a Wife is super on this), is that parents need to be able to share the care — it’s all work, dammit — and work at their money-earning jobs for far fewer hours. Which means a shorter working week, an increase in wages, way more flexibility, being able to step away from a job for two or three years … oh hold on. The full implications of attachment theory are that our current economic model demands too much from us.

And so we’ve bumped into those outdated old stories again. Those stories about the need for growth, which means profit before people, maximum extraction of what the human resources can provide in a 40 hour plus week and to hell with the externalised costs for their families and society. Plus, insecure people have greater need of consumer stuff to make themselves feel better, along with alcohol, excess food, gambling. Good attachment is bad for business.

In the week Trump was elected I noticed commentators speaking more openly than usual about our inner worlds and the stories that motivate us. George Monbiot, who returns regularly to the subject of isolation and the mental health epidemic, called for a competing narrative to the one behind neoliberalism, one that recognises humans are remarkably unselfish and cooperative. ‘What’s to be done?’ asked Deborah Orr, who has been writing powerfully in recent months about the power of our psychology to influence politics. ‘I know one thing. Politics in its current state isn’t going to help this world. Massive, high-quality psychological intervention might.’

That intervention is in our own hands, and starts with how we communicate to babies and children that it is ok for them to be dependent and vulnerable and we will meet their gigantic needs lovingly. To do this well we need support, time — which means being able to spend less time chasing money — as well as information. Having parents take time away from work to share looking after children is not enough if they’re unthinkingly pursuing the authoritarian strategies with which they were raised.

Can we afford not to provide this education, and support for parents in unravelling the old patterns so we can do things differently?

Trying to teach children to be independent of us too young is an early indoctrination into our myth of separation from everything around us, the story that has led us to threaten our very existence with ecological overreach. It’s a story worth trying to change.

Anthea Lawson is an activist and writer whose book The Entangled Activist: Learning to recognise the master’s tools is published by Perspectiva Press. She has worked on campaigns to shut down tax havens, prevent banks from facilitating corruption and environmental devastation, and control the arms trade. At Global Witness, she launched a prize-winning campaign that changed the rules on secret company ownership and resulted in new laws in dozens of countries. She trained as a reporter at The Times and studied history at Cambridge. Find out more here.

You can follow Perspectiva on Twitter & subscribe to our YouTube channel.

Subscribe to our newsletter via the form below to receive updates on publications, events, new videos, and more…

Perspectiva is registered in England and Wales as: Perspectives on Systems, Souls and Society (1170492). Our charitable aims are: ‘To advance the education of the public in general, particularly amongst thought leaders in the public realm on the subject of the relationships between complex global challenges and the inner lives of human beings, and how these relationships play out in society; and to promote research, activities and discourse for the public benefit in these subjects and to publish useful results’. Aside from modest income from books and events, all our income comes from donations from philanthropic trusts and foundations and further donations are therefore welcome. Please consider donating via the button below, or via Patreon.