Tomas Bjorkman

Oct 26th, 2020

Like all social constructs, the market could be different: we have created the market and we can change it. It may not be possible to imagine a world without a market, but it is possible to think of one where the market helps to discourage greed, selfishness, cynicism and exploitation, rather than positively encourages them.

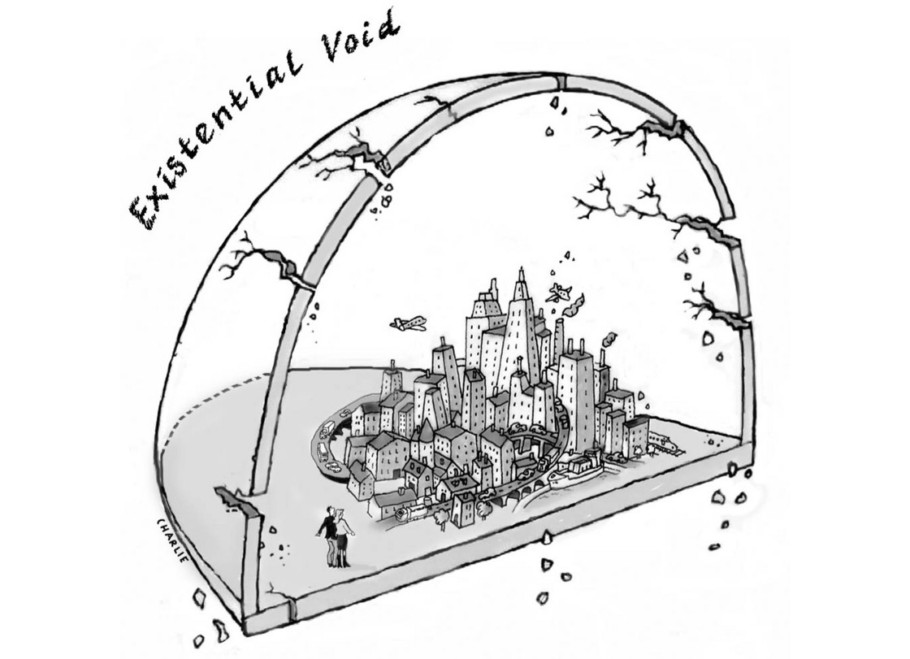

In my book The Market Myth (Björkman, 2016) I argue that market has evolved as the un-reflected answer to our need for collective co-ordination in today’s world, our need for an ultimate authority. As an ultimate authority the Market myth is very thin. As efficient as the market is for allocating private goods, it is that poor at providing a satisfying shield against our collective existential void. And we can all feel the cracks in this shield. It must address the important common question of efficiency, but also must address questions about other common human values like justice, equity and meaning. Collective questions like:

‘How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?’ require a bigger frame to be answered: A new meta-narrative.

If we want to reduce the savage inequalities and insecurities that are now undermining our economy and democracy, we shouldn’t be deterred by the myth of the ‘free market’. The first step toward the new meta-narrative may be to free ourselves of the out-dated myths of the market. We can make the economy work for us, rather than the other way around. But in order to change the rules, we must exert the power that is supposed to be ours. We need to assert the central Copernican truth: human beings should be the centre of the world, not the market.

Humans (and perhaps other sentient animals), not the market, need to be at the centre of our world; this will be the Copernican revolution of economics. Just as Copernicus once changed our view of the earth’s position in the universe, we now have to change the position of the market in our human universe.

The paradox is that the new Copernican future is, in some ways, the reverse of the one that Copernicus began. The new future means that we need not stay orbiting around an alien, implacable market system that only appears natural. We have to realise that we can be at the centre of our own universe. But we have to shape its rules to make it so.

From the Renaissance to the scientific revolution, to the Enlightenment, to full-blow modernity and its post-modern critics, we can see a similar pattern emerging. Our place in the universe is pushed farther and farther into the periphery of reality itself; we are no longer God’s chosen children, not at the centre of the world, and even our emotions, thoughts and choices are beyond us. At the same time, in what seems to be a strange and wonderful paradox, each time we are dethroned by the history of science, we rise above our previous understanding and become more intimately involved in co-creating the world — both the natural and social world, both external/objective and internal/subjective reality.

I believe that humanity has moved from not being aware of economics and the market, to understanding it as system of its own in the classical model, and that we are only now discovering how the economic reality we have been taught to take for granted was really a mirror image all along, a reflection of our own inner lives, our hopes, fears, ideas and desires. When we begin to understand objective reality better, strangely, we find that it cannot be understood without understanding ourselves as its co-creators.

The Myth of the Market

The word myth has two meanings:

The market fulfils both of these meanings.

First, it is a myth that the market produces fairness or that it maximises the common good. We will come across a number of other myths of this kind, things most experts know are wrong but that we somehow keep on believing as our ‘folk-knowledge’ about the markets. Second, the market is also the ‘big story’ — the meta-narrative — of our time: it’s the story that explains the foundations of our new global world. It even involves supernatural forces like the so-called ‘invisible hand’.

The first meaning of myth is the obvious one. We dismiss stories as myths all the time. In the next chapter we will be looking at what I consider to be the seven most dangerous myths — false beliefs — that we commonly hold about the market today, and why they are so dangerous.

The second meaning is even more interesting. This is the meaning, for example, of the myth of the creation of the world or the Tower of Babel. When we say these are myths, we are not necessarily dismissing them as false. We are saying they are not necessarily true in the narrow sense that the Battle of Hastings is an historical fact. We are saying that they are important stories that help us make sense of the world, of life and of our human predicament. Human beings need meaning and the myths we construct about life help us to put a frame around a reality that would otherwise seem chaotic.

In this way, the market is the overarching modern myth that props up our society and explains evils and injustice. It gives direction to our lives, and — as we currently understand it — it narrows down the purpose of life to making money and being a consumer. In a sense, the market is our new religion and the economists our new priests. Just like religions in the past, we have to understand that there are powerful interests that support the myth and the current functioning of society. Those who stand out and question the underlying mythology are ignored, dismissed or scolded as heretics. In another age, they might have been burned as such.

The Two Invisible Hands of the Market

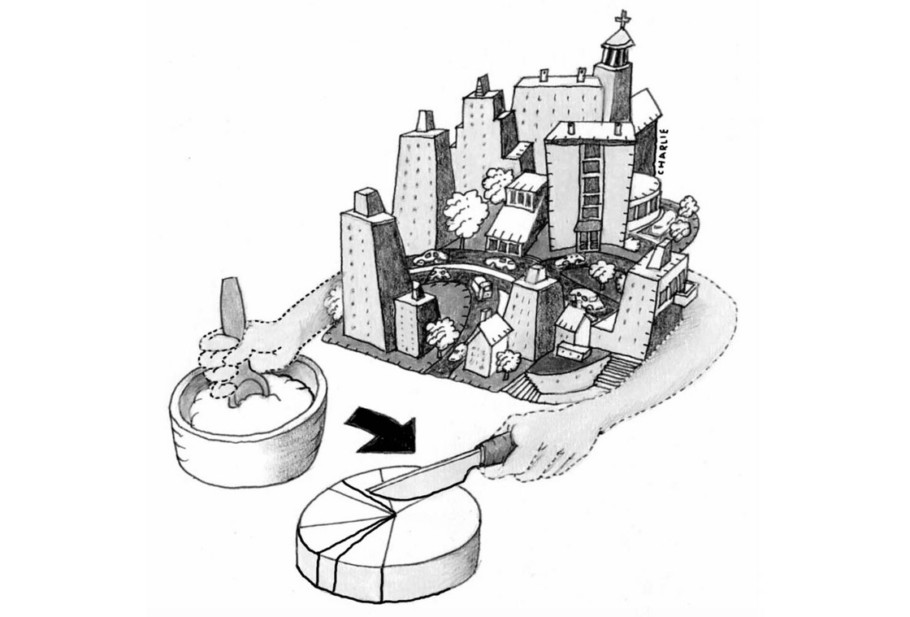

Adam Smith wasn’t entirely accurate when he described the invisible hand. It isn’t that there is one invisible hand, which manages everything — there are two of them. One invisible hand bakes the cake and one cuts the cake. Like people, the invisible hand has two hands, a right hand and a left hand. The first had takes care of the non-zero-sum game of creating wealth, trying to get as big and nice cake as possible.

With respect to this invisible hand we are all more or less on the same side, all wanting a nice cake out on the market. But when it comes to the operation of the second hand, we all tend to want a bigger piece of the cake for ourselves. It is important to always keep in mind that the market constantly performs both of these self-organising processes, and that the outcome of each is dependent on the constitutive rules of the market.

That means that, when we design the constitutive rules of the market, we need to take into account how the rules influence the functions of both these invisible hands, these processes of production and distribution. For example, when we set the rules governing the length of patents and copyrights, we have to take into account that the length of the property right will influence both the efficiency of the market and the distribution of wealth. If we have no copyrights, the market will provide much less incentive for creative production. If we on the other hand have to extended copyrights, this will limit the possibilities for reusing ideas for new productions.

Given the short-term view of the market, I would estimate that around 10 years would be optimal. From the economic perspective of an individual copyright owner the longer is of course better. No wonder big copyright holders are lobbying lawmakers to increase copyrights to 150 years. Copyrights depend on constitutive rules. One hand needs to shape the rules to encourage investment, which is the main purpose behind intellectual property. The other hand needs to shape the rules in such a way that diversity and competition is also possible, and will therefore limit the length of the IP.

We all need to ask some simple questions, when it comes to handing over any important task to the invisible hands of the market:

And couldn’t the constitutive rules be changed now? Because we now need rather different rules shaping our free market. Perhaps, in particular, we need to:

Democratise decision-making. Perhaps forms of participatory democracy can be incorporated so that employees have efficient ways of making their voices heard in the overall development of the company. This could be supported and facilitated by legal forms.

The Origins of the Myths

In 1947, the Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek attended a conference that launched an academic society influential enough to shift the way at least Western leaders view economics, the Mont Pèlerin Society. It was there that the market myth was first been spun in its current form. It was the founding moment of today’s market mythology, a myth that has caused some harm to us and to the market itself. Today, we view the market through a distorting lens, with devastating results.

In the final years of the Second World War, Hayek was living in exile London, teaching at the London School of Economics and worrying about the future of the world. He was a shy man, steeped in the victorious Vienna school of economics, and he spoke with a strong Germanic accent. He wasn’t well equipped to lead a new movement in economics that would sweep the Western world. Yet he did.

His manifesto, The Road to Serfdom, was published in 1944 just as the allied forces were liberating Europe, and was aimed at the post-war world. Hayek respected Keynes, and did not challenge him directly until after Keynes’ death in 1946. The following year, Hayek invited 36 friends and allies to meet him at the Hotel du Parc in Mont Pèlerin, near Vevey in Switzerland. There, in April 1947, he and his friends Milton Friedman, Karl Popper, and Michael Polanyi discussed the defence of what they called ‘liberalism’ in post-war Europe. The conversation laid the foundations for a revival of market economics, the fruition of which would come at the end of the 1970s.

The Mont Pèlerin Society continues the same work to this day, and meets at the same hotel every year. Its minutes remain secret. Its influence has spread over academic economics; and its propositions, which seemed so radical at the time, have now become a somewhat exhausted orthodoxy.

The events in Mont Pèlerin in 1947 demonstrate that the concepts and rules of the market are under discussion, and can be changed through systematic effort. It is a strange paradox — and it lies at the heart of the story — that those who proclaim that markets are natural phenomena, which cannot be manipulated or shaped, are themselves shaping markets day-by-day. I’m an enthusiastic participant in open markets, and I don’t believe we should put up barriers that make it more difficult to do business. But we risk losing the real quality of openness of markets if we don’t understand what they are, how they change and why they need to change.

Hayek and friends were mavericks who would not accept the prevailing view of economics of the time. But now that their ideas have been compounded and developed into a formidable new orthodoxy, it’s hard for anyone to be heard when they ask difficult questions. In fact, looking back, it was asking difficult questions that led me on the path to writing this book.

Questions can be dangerous, after all. They can make the veils fall from people’s eyes. Even if it is just a few eyes and just a few veils, this can have great impact.

The questions Hayek began asking, along with his Viennese friends, like Karl Popper and Ludwig von Mises, were about centralised state planning and the possibility of self-determination under the kind of economic controls that became so widespread before and during the Second World War. His diatribe against scientific socialism, The Road to Serfdom, took him three years to write and was finished in 1943. Three years later he travelled to the United States, supported by the Volker Fund — a philanthropic body linked to a furniture distributor and lamp manufacturer — to launch the Chicago School of Economics and to commission an American version of his influential book.

The Mont Pèlerin Society was born the next year and, in small steps, launched a movement in economics that has become the new orthodoxy. It has been transmitted partly through academics with Chicago in the lead and partly through think tanks like the Institute for Economic Affairs in the U.K. and the Heritage Foundation in the U.S., founded by two Republican staffers in 1973. It was those staffers’ ambitious document Mandate for Leadership that was handed to top Reagan official Ed Meese just two days after Ronald Reagan’s election to the presidency in 1980. By 1982, there were leaders committed to the ‘neoliberal’ economic agenda in the U.K., U.S. and West Germany, and the victory of Mont Pèlerin was all but complete. The rest, as they say, is history.

Earlier Origins of the Myths

Where did these myths of the market come from, the false beliefs that fuel the rhetoric of politicians and popular sentiment about economics? One answer is that it started with the Scottish Enlightenment during the 18th century, which gave birth to the bundle of ideas we know as ‘the market’.

Human nature and the scientific study of mankind were at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment. These were, in their new applications, original ideas. It matters to us now because, if economics were just an objective attempt to describe the world, then what Adam Smith wrote about it wouldn’t matter. But the market isn’t that: it has also become a cluster of propositions, linked to a complex series of models, built on the authority of successive economists rather as theology builds on its original texts and propositions. Smith’s original intentions matter because he constructed the founding texts of economics on which the ‘myth’ of the market is based.

The philosopher David Hume, a key player at the dawn of the Scottish Enlightenment, met with Adam Smith in 1750, and Hume was enormously influential in Smith’s construction of his economic theories. While Hume did not believe in causation — at least he was skeptical about whether you could ‘see’ what causes what under a microscope — Smith also fell back on the economic mystery of a crucial unseen ingredient, which he called the ‘invisible hand’.

‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest’, Smith wrote. ‘We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages’. It was very hard headed and very Scottish, and the very opposite of Calvinism. It was not exactly ‘free market economics’ as it is understood today. The myth was not yet clear.

Smith also taught rhetoric. His choice of the ‘invisible hand’ was to describe what was happening in what he called a ‘more striking and interesting manner’. The economics professor Warren Samuels, from the University of Michigan, investigated the original meaning of the phrase, arguing that contemporary economists had misunderstood it. They have interpreted Smith as if he was calling for less government or regulatory intervention, when he unambiguously demands regulation to defend property and for the defence of the poor against the rich. On the contrary, Smith had in his sights contemporary business people and supporters of the prevailing doctrine of ‘mercantilism’, the idea that economic trade was a zero sum game, protected at the expense of other nations.

‘Smith provided a spirited attack on mercantilism for its extraordinary restraints, but he did not extend the attack to government and law in general’, writes Samuels. ‘Indeed, many of those who do extend the attack, wittingly or otherwise, are silent about Smith’s candour’.

The difficulty for us now, two centuries later, is that Smith’s insights have settled in the minds of those who rule us in ways that are not just alien to what he meant, but which are some distance from the understanding of academic economists. This is one important origin of the Myth.

The Neoclassical Model — Our Current Myth

These models of the economy — including the model, the neo-classical one — are not as unintelligent as they might look. They are not designed, like physics is, to model the actual world. They are designed more like abstract algebra, as a way to investigate what insights a number of theoretical assumptions and abstractions might lead to.

The originators of the neo-classical model did not blunder into it. They were not under any illusions about its links to reality, or lack thereof. The problem is that outsiders to economics are not really aware of the status the model has. They have not understood what it is trying to do. As a result, they misinterpret these theoretical models, and incorporate them into the meta-narrative that supports the official worldview of the West — the myth.

It is difficult to look more closely at the myths because doing so seems to undermine important foundations of our worldview. There are incentives, economic, political and academic, to stick to the old view. Heretics do not, generally speaking, win the enthusiastic gratitude of their contemporaries, at least in their own lifetimes.

Despite these incentives, the neo-classical model of economics is under attack these days. In response to these detailed attacks, many economists have insisted that critics provide an alternative theory. In doing so, they don’t seem to realise how much the model uses metaphors to build theories.

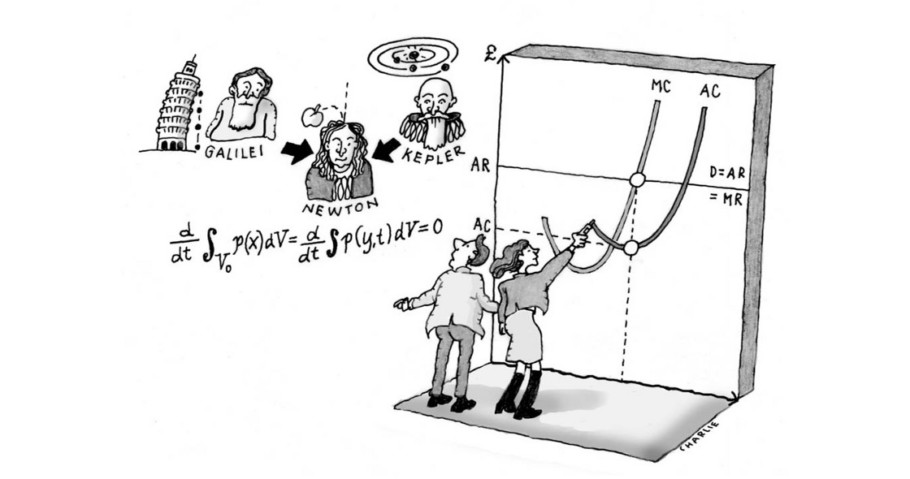

For example, the economists don’t understand how much their economic thinking has been bounded by the Newtonian metaphor, and by their search for natural laws of the economy that work alongside the Newtonian laws of mechanics. The elegant synthesis of Galilean terrestrial mechanics and Kepler’s celestial mechanics into simple mathematical formulas expressed in Newton’s newly invented mathematical language of calculus came to be the lodestar for every science during the 1800s. The neo-classical economists sought, very understandably, to express economic phenomena in the same, very potent language of calculus.

The economists knew what they wanted: a mathematical model of Adam Smith’s faith in the invisible hand. To do this, they had to make a number of assumptions that simplified economics, aware that they were not quite real. In order to arrive a model that could be expressed in the language of Newtonian mathematics, the language that has been so successful at describing nature through physics, they had to make massive simplifications.

They had to assume for example, as we will examine below, that all actors in the market are perfectly rational, that there is perfect competition and that all market actors are fully informed about everything going on in the market.

The problem is not that the economists had to make a number of unrealistic assumptions; the problem is that most of us today are not aware of the fact that they are just unrealistic assumptions necessary for the model to work. We start to believe that the assumptions are actually the way the market works.

Am I kicking in an open door here? Aren’t all students of economics 101 told these days, to remember that ‘it’s just a model’? It is true that very few people would today explicitly subscribe to an unproblematic application of the model to the real world (whatever the ‘real world’ may be). Yet it somehow sneaks in, as we have seen, into public consciousness and becomes the myth, as we have discussed.

I would even venture to claim that many intelligent and well-informed individual scholars, citizens and policy makers, are together moved by a malignant invisible hand — towards preposterous conclusions and dire analytical fallacies with resulting pathologies and instabilities in the market and society at large. The false belief in the model resides within the walls and pillars of our daily institutions — rather than with the individual student of the economy.

The model assumes that consumers are predictable, perfectly rational and conscious in their decisions. It assumes that they act from self-interest, are completely clear about what they want to buy and that they do not change their desires.

It assumes that goods bought and sold in the market are simple, owned by individuals and can be traded. It runs into difficulty when it comes to collective goods, sometimes called public goods, like military defence, culture or clean environment.

It assumes there is perfect competition, with a broad range of products from different suppliers competing on price and quality. It assumes there are always alternatives readily available in the market. It assumes perfect information, and that consumers and producers have access to all information about the item and of any alternative choices, as well as the infinite knowledge and time to evaluate it all. It assumes they can predict the future.

It is important to remember that all the above assumptions are made in order to make the model expressible in simple analytical mathematical language — the language Newton invented for physics. The assumptions are not statements about the actual market. The idea that they are actually statements about the real market is one of the main reasons for the myths around the market.

The Need for a New Meta-Narrative

My fear for our society is not so much the various external threats we face, but rather the kind of emptiness and meaninglessness that can destroy society from the inside.

Back in 1945, the philosopher Karl Popper described the difficulty the market has — not in achieving efficiency — but when it comes to generating significance, meaning or value systems. His masterwork, The Open Society and Its Enemies, warned against this lack of meaning as well as against the classic totalitarian forms of control. In earlier societies, it was the lack of food and material goods that was the biggest problem; the richest societies now faced a lack of meaning and purpose, he said. Market logic has relegated the role of citizens to passive consumers.

This is even true at the political level, where citizens are expected to push the political ‘shopping trolley’ between producers of political goods. When it comes to religion, they are reduced to choosing an individual product aimed at their personal needs. Even our love lives are reduced to a commodity where potential partners are considered as products to be kept or dumped, and who rarely live up to the marketing promises of magazines and media.

The market system needs no sense of meaning to work, but both society and individuals do need a system to create meaning. We need a cohesive force, common ideals and goals in order to survive and flourish. We need to operate within a context to know that we are part of something meaningful. Without a cohesive force, society unravels into a collection of individuals who are mere economic entities in the market. A society cannot consist of consumers and producers only, yet this is the vision of our world promoted under the current market-liberal worldview.

As discussed earlier, one definition of myth is that it is the ultimate justifier and ultimate authority in a society. This kind of myth provides the meta-narrative — the big story — that keeps our society together in what may be an arbitrary, but also a necessary way. It is ‘sacred’ because there is nothing beyond it that can help us value it. The myth is untouchable and beyond our judgements. It ‘just is’. In its sacred way it shields us from our collective existential void: it hides the fact that it is all up to us to create human values, meaning and purpose. It shields us from the fact that we have to provide our own ultimate authority on which to build our otherwise completely arbitrary society.

Every society, every culture, has got its own outer boundary: its meta-narrative. For our emerging global society it is the Market. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there was just one contestant for a global meta-narrative remaining. The market claimed to be the ultimate ‘sacred canopy’. This would suggest that we have abandoned our search for collective meaning, replacing it by a pursuit of individual utility.

In practice, the market serves the same purpose as God or Science once did: to provide us with an external ultimate authority. We have reverted back to living under false absolutes, rather than living authentically, as the existentialist philosophers urged us to. We believe that somehow, and uniquely, the market ‘just is’. We are, in short, still alienated from our systemic freedom.

So far in history we have handled this by pretending that this freedom does not exist. We have deferred our decisions to an external ‘ultimate authority’ of different kinds in different societies and different points in history: God, Science or the Market — at each step increasing the complexity of our meta-narrative to meet the increasing complexity of our world. And now we need to do this again. We need a bigger collective frame of reference.

The market has evolved as the un-reflected answer to our need for collective co-ordination today’s world, our need for an ultimate authority. As an ultimate authority the Market myth is very thin. As efficient as the market is for allocating private goods, it is that poor at providing a satisfying shield against our collective existential void. And we can all feel the cracks in this shield. It must address the important common question of efficiency, but also must address questions about other common human values like justice, equity and meaning. Collective questions like ‘How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?’ require a bigger frame to be answered: A new meta-narrative.

Hayek and his friends at Mont Pèlerin in 1947 were mythmakers. They were busy re-writing the story for our times and, as we have seen, this was propagated to the world as more than just economic doctrine. But at least that shows that it is possible for humanity to grasp the myths that govern the world and to re-write them. Hayek and his colleagues did it — and we need to do the same.

But there is a problem. It isn’t easy. And that’s not the half of it. The most important step is to realise that, together, we have a systemic freedom to shape our ‘free market’ — but, to do so, we need a larger frame by which to evaluate it so that we can change it. To know what is best for the market, we need a yardstick by which the market can be assessed, a meta-narrative that goes beyond it and allows us to see and judge the market from this bigger frame.

To put it another way, we need a means by which we can agree on the common good that is the ultimate purpose of the economy. What do we want ‘the two hidden hands of the market’ to deliver? The market itself is such an amorphous idea that it provides us with no means of judging anything. How do we define the common good? How do we define equity and justice? How do we balance our needs today with the needs of future generations?

And, again, the important insight is that these human values — as opposed to subjective qualities like beauty — cannot pertain to the individual and her preferences alone. Ethical values must have a collective aspect. Justice and meaning are values that do not exist outside our common social reality. They are created in the relationships between individuals, not within single individuals. They are integral parts of our socially constructed world that we share with other people.

Final Words

First insight: We as humanity hold a systemic freedom to shape the market, a freedom we can only exercise collectively.

Second insight: We are in dire need of a bigger common frame than that of the Market, in order to be able to use our systemic freedom to create our social reality; not only for efficiency and individual interests, but also for the common good. We need a new meta-narrative.

The third important insight: We will never find this frame of reference, this meta-narrative ‘out there’, as an object in the natural world, like we thought we had done with God, Science or the Market. We realise that all meta-narratives are in some way arbitrary and they are all man-made — but we still need them in order to survive and flourish, both as individuals and as humanity.

Now we have to face the fact that we can look for no other place to find this meta-narrative than ‘in here’, in the dialogue between humans. Our biggest frame of reference is always man-made and arbitrary. This is a source of enormous collective existential angst and the reason why we mobilise all our internal defences to avoid addressing it. It feels so much better just to continue pretending that we are in the hands of an external ultimate authority.

Previous generations might have reached for religion to provide the framework of a narrative by which they could judge the market, but that isn’t a path that is really open to us now. There are too many competing religions, and the insights of post-modernism suggest, anyway, that all meta-narratives, including religions, are man-made. This is both a problem and an opportunity. The problem is that we can’t rely on God, Science or the Market — or any other external authority — to provide an objective meta-narrative. But there is an opportunity: we are free to create one.

There is also a threat. Without a meta-narrative, secular market society has no proper roots and is in danger.

This brings us back to the main problem: where can this new global meta-narrative to come from, especially when we have no means of agreeing on anything globally, and when the prevailing post-modern world view is suspicious of collective ideas of all kinds? Yet if we don’t all somehow agree on the frame, some of us are bound feel that the prevailing market relationships will have been forced upon us. This could be a new, more subtle, form of colonialism. So how do we build a new meta-narrative when we come from so many different, irreconcilable perspectives?

We will never reach a final form of this narrative. There will be a continuing process challenging it and keeping the dialogue alive. It is, in that respect, the most important project in human history: it began many millennia ago, but it has also only just begun. As complexity in our society increases, every so often this process gets stuck in a cul-de-sac — as it has done recently — and needs to be kick-started again.

Tomas Björkman is co-founder of Perspectiva and an applied philosopher and social entrepreneur with a great interest in science and philosophy. He has founded several companies and organisations, including Investment Banking Partners AB, and has also been chairman of EFG Investmentbank AB. He founded the Ekskäret Foundation, with the purpose of stimulating the sustainable development of individuals, organisations and society. He’s also the author of several books, including The World We Create, The Market Myth and co-author of The Nordic Secret, and the initiator of the Emerge network and media channel. Find out more here.

You can follow Perspectiva on Twitter & subscribe to our YouTube channel.

Subscribe to our newsletter via the form below to receive updates on publications, events, new videos, and more…

Perspectiva is registered in England and Wales as: Perspectives on Systems, Souls and Society (1170492). Our charitable aims are: ‘To advance the education of the public in general, particularly amongst thought leaders in the public realm on the subject of the relationships between complex global challenges and the inner lives of human beings, and how these relationships play out in society; and to promote research, activities and discourse for the public benefit in these subjects and to publish useful results’. Aside from modest income from books and events, all our income comes from donations from philanthropic trusts and foundations and further donations are therefore welcome. Please consider donating via the button below, or via Patreon.