Liam Kavanagh

Sep 15th, 2021

‘The stakes involved in loosening the hold of the equality complex are high. The ecological crisis stands to be tragically unequal in its consequences and the potential scale of injustice will become more triggering as climate change progresses’.

– Liam Kavanagh

This essay is adapted from the book Collective Wisdom in the West: Beyond the shadows of the Enlightenment, published by Perspectiva Press.

Read & download the essay as a PDF here: The Equality Complex

The full essay is also available to read below.

The Equality Complex

By Liam Kavanagh

‘Equality does not bring suffering but an equality complex can’

– Thich Nhat Hanh

When I was a schoolchild, my classmates and I were told that ‘you can all accomplish anything you want, if you set your mind to it!’. It seemed strange when I looked at the giants who played American football and basketball. When I went to college, I remember running into a few people who felt that being a feminist meant disputing that there are differences in average strength between males and females. And more and more I’ve heard it objected that ‘you can’t generalise!’ when seemingly any statement is made about differences between groups. At the same time, I was disturbed by how much less value was placed on the lives of Iraqis and Afghans than on Americans during wars waged by the US in those countries.

All of these examples touch subtly on our ideals of equality and their tendency, at times, to be distressingly at odds with the reality we live in. A long erosion in the self-confidence that allowed the West to label an era of its own history ‘The Enlightenment’ has largely left equality without reexamination, even while our profound confidence in rationality has been questioned. This essay asks if this is a good thing, not because equality is a ‘bad idea’, but because our ideals are overrated as a means of both understanding the deepest sense of equality and honoring it in our lives.

I argue that, behind much of our social dysfunction and culture wars, there is a subtle but deep confusion between two senses of equality: the equally sacred nature of all human lives that our wisdom traditions strive to appreciate (which I call deep equality), and on the other the systemic equalisation of opportunities, rights, and outcomes (surface equality). In the first part of this essay, I explore these two senses of equality, and show how they’ve become joined through a powerful narrative that views the West as respecting and protecting the natural sacredness of humans with the aid of rules. In the second, I will discuss how this narrative has sometimes started to ring false, and why this crisis in narrative shows that we must constantly grapple with the tension between ego and pride on one hand, and our sense of deep equality, on the other (as our wisdom traditions always counseled). In the third section, I explore how our current culture war conversations evolve out of a deep contradiction: pursuing morality within societies that see the merits of people – their capacity to achieve – as the measure of their value and thus abandon the truth of deep equality.

Specifically, our meritocracies aim to give all citizens an equal chance to be measured as greater in status through their efforts, which is very different than respecting equal sacredness, but cannot summon the capacity to deliver on this promise. Culture war tactics labelled as PC and identity politics arise as impulses to fix this system’s shortcomings, but mostly accept its assumptions, and so miss a chance to restore appreciation of human life. I explore what wisdom traditions say about how greater appreciation of deep equality can be achieved within secular culture, asserting that if this is impossible then secularity, as well, may need some serious reexamination.

***

My argument must start with a deeper exploration of the two valuable, distinct, and related senses of equality that we’ve mixed together. The first, again, is the equal sacredness of lives, which I will call ‘deep equality’. Defining sacredness may be impossible(1), but I agree with the sociologist Gordon Lynch that humans need this word to gesture towards ‘absolute realities that exert a profound moral claim over their lives’.(2) In other words, deep equality is the ‘self-evident truth’ that life is equally present in all humans, which we can only deny self-destructively, as does the person who experiences a part of themselves dying while becoming a killer.

The second sense is equality among people in valued opportunities, outcomes and traits, which I call ‘surface equality’. Surface equality is not unimportant or shallow, it discusses things that are easier to fully see (closer to the surface) than sacredness of life, like outcomes, opportunities, and traits or talents. Appreciation of deep equality is available to all humans but is only constant and total among buddhas and saints, and surface equalities can help us behave more like saints without always having saintly hearts. Provision of equal opportunities and outcomes represent different ways of providing for human welfare, and creation of these rules can be motivated by a deep sense of what matters to humans, but they can also become misguided if their use is not guided by a direct observation of reality, what is actually true in any situation and what truly matters. Like any ideas, surface equalities become dangerous when they become ‘the truth’.

One traditional expression of deep equality is: ‘we are all equal in the eyes of God’ – a Christian idea that influenced Enlightenment philosophy. Martin Luther King articulates in his sermon on ‘The American Dream’:

…. This morning I would like to deal with some of the challenges that we face today in our nation as a result of the American dream. First, I want to reiterate the fact that we are challenged more than ever before to respect the dignity and the worth of all human personality. We are challenged to really believe that all men are created equal. And don’t misunderstand that. It does not mean that all men are created equal in terms of native endowment, in terms of intellectual capacity – it doesn’t mean that. There are certain bright stars in the human firmament in every field … What it does mean is that all men are equal in intrinsic worth.

You see, the founding fathers were really influenced by the Bible. The whole concept of the imago dei, as it is expressed in Latin, the ‘image of God’, is the idea that all men have something within them that God injected. Not that they have substantial unity with God, but that every man has a capacity to have fellowship with God. And this gives him a uniqueness, it gives him worth, it gives him dignity. And we must never forget this as a nation: there are no gradations in the image of God. Every man from a treble white to a bass black is significant on God’s keyboard.(3)

The first paragraph is very natural to read within a secular mindset, but in the second, King turns to theology. This is not only because King was a religious man, but because the feeling behind this paragraph is impossible to ground in a way that does not strain past the limits of rationality.

The Christian contemplative Thomas Merton describes the same insight in a slightly less religious language:

In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realisation that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the (monastic) world of renunciation and supposed holiness …. This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud …. I have the immense joy of being man, a member of a race in which God Himself became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now I realize what we all are. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.(4)

Merton describes something that most of us merely glance in flickers of intense camaraderie, before being drawn back to self-isolation. As a non-Christian I see ‘equality in the eyes of God’ as a metaphor that invites me to inhabit a ‘God’s eye view’ from which I see others and myself like a loving parent would see their many children: all equally unique, and equally loved.

King and Merton’s particularly eloquent descriptions may convince us that a few people have fully seen the sacredness of life we’ve sometimes glimpsed, and arouse a yearning to see this precious truth more fully and more often, but cannot hand us an experiential understanding of what it is like to see others this way. I doubt it is very different from what we meditators describe with the term ‘the insight into interbeing’(5), which is summarised by saying something like ‘what we see as the self, separate from others and the world, is totally dependent on and meaningless without these’. Such descriptions are often followed by the caveat ‘you just have to be there to understand’. So, if the reader wants to better understand deep equality it may be more appropriate to contemplate the preciousness of others’ lives for a moment than to puzzle further over whatever additional verbal definition I might provide.

Culturally, we skip past this difficulty by speaking of this inherent dignity as ‘self-evident’, as did the framers of the US Declaration of Independence and the more recent Declaration of Human Rights.(6) Deep equality is clearly not that self-evident or history would be very different, and we would not need governments, protests, rebellions and rights to make us act as though we appreciated this equality. Deep equality is only ‘potentially self-evident’ to everybody, and perhaps truly self-evident only to those who manage to see what King and Merton saw, often after years of practice.

Few people want to live in a world where their lives’ sacredness is denied, and though living among saints is desirable, it seems more realistic to take ‘down from the mountain’ some simple rules that we can follow, and expect others to follow.

That is what is so useful about what I’m calling ‘surface equalities’: they help to address ethical questions in clear, codifiable and ‘actionable’ ways. For example, how should political influence be spread? Equally, one person equals one vote. What educational opportunities should children have? Equal. What should every person’s chances of being drafted to war be? Equal. Some societies influenced by enlightenment ideas have gone further, declaring that income and ownership of capital should also be equal. The enforcement of such clear rules can increase human well-being even among groups with little spiritual insight, but agreeing to adopt and enforce such rules is difficult, it can be the cause for bloodshed. I will briefly explore two major attempts at rules of equality: equality of outcomes and equality of opportunity.

Equality of outcomes is intuitively attractive: if humans really loved each other like dear friends, they would share possessions like one big happy family, there would be little in the way of abject poverty, and so on. Some need more than others, of course, but this is hard to determine, but we can move towards this state with a rough-and- ready rule: equality of rights and material outcomes.

We can see this idea in action when the proverbial (pizza) pie is carved up. Among a group of friends, pizza is shared according to needs because friends appreciate each other’s needs. But as soon as the relationships of people are less close, pizza is scarce, there are too many pizzas and people to keep track of, or some people get there earlier than others, then our ability to share considerately is challenged.

The number of pizza slices per person is figured by division, and slices are counted and handed out carefully. It is generally acknowledged that everybody being equally well-fed is the best outcome, but getting there is a challenge in a society of imperfect people. If the cooking or buying of pizzas for a large group is consistently left to a few people who receive no incentives such as credit or compensation, less pizza tends to be made (mirroring a social tendency for less overall production if all produce is shared equally).

Equality of opportunity often seems the more pragmatic approach. We don’t have to divide the total amount made equally, but we can give people a (truly) equal chance to get pizza according to their desires. The problem is that measuring opportunity can also be hard, making it difficult to confirm that all have equal chances and check impulses to grab more opportunities. For the highly influential philosopher John Rawls, ideas of equality of opportunity did not just demand that careers should be open to all but also that ‘those with the same desire and ability to succeed should have equal chances at success’.(7)

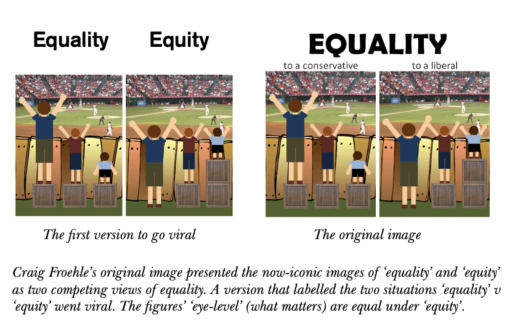

The difficulty of actually achieving equal opportunity on a social level is well illustrated by a popular meme that shows the distinction between equality and ‘equity’ or fairness. In this (left below) ‘equality’ is represented by a situation in which three people have the opportunity to stand on a box in order to watch a baseball game, but are of such different heights that one doesn’t need a box and another would need two in order to see the game. ‘Equity’ is achieved by redistributing the boxes so that the eye-level of all three (what matters) is equal. It is worth noting that ‘equity’ could be seen as the same as Rawls’ equality of opportunity, depending on whether we see the talents required to watch the game as including only a pair of eyes, or long legs. That there is little difference between equity and a well guided sense of equality is reflected in the original version of the image (below), made by Craig Froehle, who described the images as showing contrasting definitions of ‘equality’.

Labels (and political judgements) aside, the image provides a simple illustration of the limits of surface equality in guiding us clearly to saintly behavior. Even if all have equal rights to speech, to apply for a job, or chances to go to school, some have the megaphone of media, social connections, or the ability to devote more time to study and hire tutors. Thus, the equal rights, and opportunities to apply for jobs and attend public schools provided by society do not really give us equal chances to achieve. The images really show that we can define equality of opportunities easily on an abstract level, and in some specific situations such as the one pictured (this is why it is pictured), but not in many specific situations. For example: what is equal access to media? Under arguments for ‘equal time’ in media coverage, climate deniers and creationists present themselves in the position of a person who unfairly is refused use of a soapbox.

I worry that the popularisation of the new term equity, as a substitute for equality of opportunity, risks suggesting, subtly, that new ideas will create fairness or justice. The new terms would be unnecessary if application of old ideas were matched by an appreciation of sacredness. A person in touch with deep equality looks at the two situations pictured and is in touch with the joy and suffering of the characters, and knows that the one on the right is better. The adoption of the term ‘equity’ is an attempt to intellectually differentiate the two situations in a way that can force us to choose the right, not because we are guided by our felt sense, but because a conceptual understanding points us clearly to the right based on the visible creation of greater and more equal benefits for all. As I will discuss at length in the final section, this intellectual route is the one our secular culture has taken, almost exclusively. It is not a totally vain pursuit, but I see no way of arriving at the dream made so famous by Dr. King via this path alone. Our path must merge onto a road towards insight into deep equality.

So, surface equalities are quite distinct from deep equality, but these ideas get mixed together for a number of reasons:

Firstly, related but distinct notions get confused when they share the same name (‘being right’ versus ‘being within your rights’).

Second, they are related: when deep equality is appreciated less surface inequality occurs.

Third, just as the flexibility of a yoga practitioner is more visible than the inner discipline that allows stretching, and many other things, and so becomes a yogi’s measure, more visible measures of surface equality become the measure of a person’s appreciation of human equality.

Fourth, deep equality is easier to fake and so it can feel less real than surface equality: it is easier to pretend to love others like oneself than to pretend to pay them as we pay ourselves.

Fifth, deep equality falls within territory that is traditionally called spiritual or religious, and it has become taboo to discuss politics while standing in religious territory. In contrast surface equality is comprehensible to the intellect and fits comfortably into secular society.

These factors have allowed these two equalities to be collapsed together into a popular notion of equality that is totally integral to our society’s sweeping and ambitious story (or myth) of social progress and sense of justice. These two equalities became bound together because we carry, in our emotional core, the experiences of ancestors who were serfs or were enslaved at the time of ‘The Enlightenment’ and who slowly struggled to become ‘equal citizen’ members of meritocratic capitalist states, and who experienced along with this legal arrangement a greater recognition of one another’s sacredness.

By coupling equal citizenship and recognition of deep equality in our imaginations and imagining legal and intellectual strategies for extending surface equalities in rights expanding across social and geographical barriers, it has been possible for the citizens of Western democracies to see themselves as a part of a quest to extend appreciation of sacredness slowly across the world. This is the story of universalism, defined by the Oxford English dictionary as:

|

Loyalty to and concern for others without regard to national or other allegiances. |

|

Which is often argued to be a reworking of Christian Universalism(8): |

|

The belief that all humankind will eventually be saved. |

|

This story of progress is certainly a Western myth in the sense of the word used by Joseph Campbell: a story with no author that helps us make sense of our lives.(9) We are starting to ask ourselves if this story is a myth in the more usual sense: an appealing but untrue story. That is, we’ve been struggling against the difficulty of acting out, within our materialist, meritocratic culture, the story of equality that we’ve collectively authored. The feelings of superiority and the will to supremacy underneath old disavowed ideas and laws were never extinguished and have often been stoked in the hearts of the newly equal. Discrimination is widespread indeed, while nowhere in the word of the law. I suggest that we should be realising, by now, that our prefered methods ─ideals, norms and rules based on surface equality ─can only take us so far towards a society that respects the sacredness of life. |

***

In this section I will further explore how surface and deep equality have been fused in the Western mind through civilisation-wide stories, how this myth has been challenged, and how a shift towards approaches favored within spiritual circles, including insight into deep equality, becomes vital for its renewal. But before going further, I would like to invite the reader to consider an experiment which I find helps people to get emotionally in touch with their relationship to equality.

Please consider statements of the form: ‘________ is not a source of suffering, but an obsession with _______ is’. For example:

Money is not a source of suffering, but an obsession with money is.

Achievement is not a source of suffering, but an obsession with achievement is.

Being good-looking is not a source of suffering, but an obsession with being good-looking is.

There are many things that do not cause suffering, but an obsession with anything is a source of suffering.

You might even try inserting ‘rational explanation’, or ‘individual freedom’ in the blank.

The many people I’ve tried this experiment with agree with the above statements, but many get uncomfortable if I say:

Equality is not a source of suffering, but an obsession with equality is.

That line is a paraphrased version of a statement by the Zen Master, Thich Nhat Hanh, that I started this essay with:

Equality does not bring suffering but an equality complex can.

An ‘equality complex’ might make us suffer by putting us in a chronic state of comparison, disrupting our ability to experience ourselves as a ‘we’. Both those guilty about having more and upset about having less experience themselves as more separate from each other the more their interactions are mediated by comparisons and rules that are not grounded in common feeling. This suffering can be called disconnection, or separateness in the language of buddhists, while academics might call it social alienation.

To underline the point, the more we are fixated on taking intellectual approaches to our relationships to others, the less we are in a mindset capable of directly experiencing deep equality, which cannot be understood intellectually.

To put it in more familiar terms, comparing our level of social status with others tends to put us ‘in our head’, separate from others, and yet the ability for ‘heart-to-heart’ connection is important for actually taking difficult moral actions. This is akin to losing the beauty of the whole through fixation on analysing it as an assemblage of parts, a process so lucidly described in the works of Iain McGilchrist.(10)(11) Readers will know the difference between calmly making use of measurements (surface (in)equalities) versus being obsessed with them from experiences with social media followers, managing weight, school test scores. Surface equality, I contend, is a major means by which we’ve intellectualised moral life, turning it into a matter of measurement. As happens with weight and test scores, the more we have failed to live up to our ideals, the more obsessed with measurements we become.

As a way of honoring and navigating the emotional charge around ideas of equality, I feel I should discuss how my identity as a white male affects my discussion of them, which is a source of questions for some readers. For example when people hear Thich Nhat Hanh’s quote many become puzzled, slightly uncomfortable or intrigued, but when I repeat these words, many in my left-of-center circles say something like, ‘but we can’t just accept massive inequality!’

I could reply by noting that if a person says, ‘I think being obsessed with looking good causes me suffering’, we do not assume that she means, ‘I’m going to just accept looking terrible’. Analogously, by questioning an obsession with equality, I am not simply accepting inequality. But this might not address concerns about my personal motivations. I am a white male Zen non-master, with great privileges that many would reasonably suspect me of protecting by using this quote to question equality. Since I have an ego there is reason to suspect me of subtle evasion of responsibility, rather than intelligent concern.

So how can I ‘question equality’ when my identity group, white men, would have so much to lose in a great equalising of privilege? My responses are two: First, if a person’s motivation to preserve their privilege can be assumed to trump genuine concern then the conversation seems pointless – it is doubtful that there will ever be social justice. Secondly, the ideals of equality that I am reexamining, especially those based in surface equality, are what white men have been relying on while becoming, and remaining ‘more equal than others’, so a better world likely demands their questioning. Both of these points will become clear I hope, as we consider the Western myth of moral progress from a few angles.

Until a short while ago white men would teach and be taught a version of history that cast them as heroes (with varying degrees of subtlety, depending on the storyteller). In this telling of history, Europeans broke the hold of hereditary rule on humanity and together constructed societies made of equals. According to that telling of history ‘we’ created a system of equality before the law that people agreed to collectively, which served everybody’s interest in personal freedom, and together we protected this system from kings, dictators and anybody who wanted to return to the old system of superiority was a threat to the people under this new system. People protected by clear laws and norms relying on ideas of surface equality were free to interact with each other as equals, express themselves as equals, and in fact acquired a heightened sense of each others’ sacredness, entering into a more perfect union. Though this system, which respects deep equality and is engineered with surface equality, started among white men, it would eventually reach all of humanity.

Another way of summarising the history of equality, which white people are less inclined to hear, is that small groups of white males agreed among themselves to overthrow kings and create a regime of equality among themselves because it was the only norm that all could agree on, and in which each had a self interest in promoting. After creating systems of equality among themselves, white males have used superior technology to create empires, and impose their wills and desires on others. A few persons showed greater will to see what a commitment to deep equality implied, for example dedicated abolitionists and anti-colonialists, but these were few in number and society fell far short of promises to extend equality to oppressed people. Still, descendants of the colonised and enslaved are faced with horribly unequal treatment by police and courts. Very little has been done to equalise the massive differences in incomes between rich and poor within Western countries or between rich and poor countries despite all the talk about equality. It took a very long time for explicit justifications of inequality to be discarded, and even then, cultural barriers stand in the way of equal opportunity. This retelling casts white men or white people in general in the role of cynical users of surface equality for their own ends.

There is still another way of looking at the history of equality, which is not more rosy, and perhaps more accurate. Many groups successively moved into the privileged class that I am now part of, and each fought mostly for their own equality. Once they had greater legal equality, these groups ─starting with nobles, then rich white men, then progressively poorer white men, and finally women, people of colour and non-cisgendered people, in varying order seemed happy to remain ‘more equal than others’ (as Orwell put it in Animal Farm). To take one example, today’s privileged group of whites often seems to be imagined as a coherent whole going back a long time. It is actually a constantly shifting invention, with groups that used to be oppressed (poor landless peasants, penniless Slavic, Italian, and Irish immigrants) slowly moving into a dominant group that remains as small as possible while remaining dominant. To take another example, many people outside the borders of the West are still denied many rights, but no ethnic group has ever objected on behalf of those groups as loudly as they do for themselves(12) (though we can find individuals).

The famous group of black lesbian feminists known as the Combahee River Collective, who coined the term ‘identity politics’, remarked on this tendency, which explained why they absolutely had to advocate for their own rights and dignity.(13) The women’s rights, civil rights and gay rights movements made gains, but left members of this collective, at the intersection of these three oppressions, still marginalised.

So, the ability of successive waves of people fighting for surface equality has shown its limits in producing both general protection from laws and general mutual respect. If the privileged cannot act collectively from a sense of deep equality then the great dream will forever stay out of everybody’s reach. The balance of political power will never be on the side of erasing inequalities of opportunity because the group which is privileged with superior opportunities can expand itself enough to maintain its dominance, while excluding billions.(14)(15)

Many powerful reactions can arise when this sinks in, and a person brought up on the old story asks themselves if, really, their ancestors have mainly popularised the practice of fighting for their own group’s equality with the ruling class while relying on the stirring language of universal equality for rhetorical effect.

Some common reactions are to separate oneself from this trend by: claiming (usually falsely) to have broken with history; redeeming oneself through guilt; attacking others who are still less committed to equality. Alternatively we can reflect on the difficulty of breaking this pattern: the root of our unseriousness about inequality is ego, which is here to stay. This leads to sadder reactions, some decide that our ideals are a joke, and find comfort in distant resignation to humanity’s hypocrisy by embracing numbing nihilism, and some cynically conclude that ideas are only weapons to be used to our benefit. None of these responses do much to change passion-driven habits. Really, they all feed ego.

Perhaps, our difficulty in living up to our ideals should teach us to accept a few hard truths. Having an ego means you don’t want to be equal, but better. Having power means that you don’t have to be equal if you don’t want to be. So, as long as there is power and ego, especially at the group level, there will not be equality in outcomes or in opportunities. Those who would like to see the recognition of human sacredness reflected in international affairs, and domestic income distribution can only descend into resignation if we ask ourselves what is still worth doing, despite these facts, and find that the answer is nothing.

Fortunately, wisdom traditions, from Christianity to Buddhism to therapy, can teach us that acceptance does not mean resignation. Acceptance, especially compassionate acceptance, can be the best way to see inside ourselves the roots behind destructive individual and collective actions and, also, good parts we might miss when dwelling on failures. We can then see the necessity for change. Compassionate acceptance is, for example, the first step in 12 step programmes for facing habits like pathological lying, drinking heavily, or spending too much time on social media, allowing us to attend to them without being repelled by feelings of guilt. It is important to note that compassion for another person does not imply an unwillingness to directly intervene in their behavior – many people have worked to improve the lives of prison inmates while accepting the wisdom of their continued imprisonment. Compassionate acceptance is known to us at the individual level, but I suggest it can be helpful in understanding our society as well.

So the point of reviewing our history, perhaps a bit brutally, was not to wallow in guilt or inflict it, but to look deeply enough at our society to see if our dream is even possible, and if so how. I wrote this essay because I think it is, if we have the courage to know the people who must make this dream possible: ourselves. Compassion, an awareness of suffering that is sympathetic, and even quietly enjoyable, can allow us to see the tension between two parts of our divided nature: our will to (collective) power, and also our capacity for seeing deep equality, both of which are occluded by an obsession with self-judgment.

Our desire for power over others is inherently in conflict with both deep and surface equality, making it taboo to express or pursue. This may explain why Europe’s colonial history and the US’ current un- acknowledged empire are so badly understood. Empires, whether they were made by ancient Persians or Romans, the Mongols, the Aztecs or modern Europeans serv(ed) desires for collective experience of power and glory. European empires proved that a society in which citizens agree to pursue equality among themselves can still satisfy citizens’ drive for power by dominating people outside that society. This powerful drive only relented among Europe’s great states after the pursuit of national glory erupted into two empire-shattering worldwide wars that claimed tens of millions of lives, and resulted in atrocities so ghastly that they forced Europe to question its claims to civilisation. The consequences of maniacal pursuit of national superiority played a large part in convincing Westerners to discard explicit ideas of superiority and embrace ideals of equality with fervor.

This cultural legacy is impossible to reckon for minds who’ve inherited the notion that imperfect commitments to equality are to be fixed by harsh judgements and guilt. The reality is that our ancestors gave us our minds, we are them, and we must eventually judge ourselves if we judge our ancestors. If our judgements are a form of psychological violence, our attention will dart away from the past. The habitual thoughts of superiority that our ancestors cultivated are still with us. It is doubtful that any mind, much less the most privileged minds of Western civilisation in unison, can be forced through acts of will to make themselves behave like saints through guilt. As Nietzsche remarked over a century ago,(16) large groups and especially social ‘superiors’ have forced guilty feelings onto wayward members especially the socially ‘inferiors’, a whole group seldom forces itself to do anything through guilt, apart from avoid knowing facts. Our culture is far more likely to fathom its history deeply enough to learn from it through the awareness that self-compassion allows.

Compassion can also allow us to admit our capacity to see deep equality, rather than focusing on failures to act in line with our great aspirations. Those whose equality is recognised have often derived great joy in seeing others become recognised as more equal, as our ancestors did. Take, for example, a recent abrupt shift that readers have personally experienced: the change in feeling that comes from being able to express open admiration, friendship and love, platonic or otherwise, for lesbian, gay and transgender people is uplifting for many, even it is small in comparison to the uplift that lesbian, gay and transgender people themselves have felt. In former times similar emotions were felt by members of the abolitionist movement, white supporters of civil rights, men who supported women’s suffrage and so on. Even if the privileged do not equally share the joy of those who’ve become more equal, their hearts have often been swayed towards aiding these causes. The mind bent on changing behavior hesitates to admit any good because this lightens the weight of psychological punishment which is supposed to push the judged person towards better behavior. This is true whether we judge others or ourselves. As I argued above, if we are to arrive at the dream, society as whole will have to truly want it. We will have to get deeply in touch with the part of ourselves that is capable of wanting such a thing, rather than denying it.

None of this is easy. Leaving the work of more serious appreciation of deep equality to individuals might sound like wishful thinking, and a call to scale such ‘moral heights’ together might sound like a call to a public religion (like mindfulness classes did a short while ago). A contemplative, compassionate route to social justice has seemed barred by a distrust based on a long history of oppressors who loudly espoused the high moral aspirations of religions.(17) Also, the great challenge of such a route lies far outside our secular culture’s comfort zone, and so it is easy to brush off.

We have good cause to be concerned about the pitfalls of the spiritual route, but if cultivating our capacity to understand deep equality is not an option, we will probably stay with what we know.

We will see surface equality based ideas, rules and arguments as levers which, if we pull them hard enough, can bring justice to us, or as weapons that we can use to fight inequality. As I will argue next, this is what we’ve been trying, mostly, and the results have us questioning whether our deepest aspirations will ever come true.

***

In this final section, I turn the discussion to the strategies for equality and social justice that Western societies have actually pursued, which have become confused through avoiding the subject of deep equality. We have not accepted that, as just argued, power, ego and residues of our past must be accepted compassionately and directly grappled with, as they impair our hold on deep equality and thus, our equal treatment of others. Rather, our meritocratic society has tried to resolve the challenges that our egos and the West’s prejudiced history pose for its behavior by combining formal equality of rights and opportunities with enthusiastic status-seeking. This compromise introduces subtle distortions to various aspects of our culture.

In theory, meritocracy gives citizens an equal opportunity to achieve what they can, encouraging dynamism and innovation, and meritocratic ideals do not contradict deep equality. In practice, our meritocratic system values citizens very differently, according to their (perceived) capacity for achievements,(18) but citizens do not have equal chances to show their true merits because prejudice persists, and the powerful are in position to give themselves better chances. Also the dynamics of capitalism produce massive disparities in merits that often seem to have little to do with a person’s contribution to society.

Much of culture war behavior evolves out of attempts to correct contradictions in this system, and save progress, motivated by a mixture of genuine concern and desire to show moral merit. The contradictory vanity of being morally superior by ‘standing for equality’ thus emerges, often involving the use of sophisticated intellectual criticisms produced by progressives in the university system. The more the outcomes of society offend our felt sense of deep equality or our ideals of surface equality, the more invested liberal critics become in using weaponised concepts of surface equality to correct these outcomes. Because tactics based on surface equality are often too simple to do justice to reality, they can be ridiculed and dismissed by defensive conservatives, and the less in touch with each other’s deep equality we all become. Though the contemplative turn I suggested at the end of the previous section may sound fanciful to some, I argue that it is more pragmatic than expecting our old way of thinking to produce anything but more of the same.

My starting point in explaining contemporary Western difficulties in the pursuit of social justice is a taboo fact: meritocratic societies openly value the talented and hard-working more than others. We favour people who we more enjoy looking at, who have nice houses and can give us jobs, who can come up with clever ideas and bold actions. We pay greater attention to them, including their pain and suffering.(19) When a high-profile athlete dies young, it is a national tragedy, but if his lesser-known teammate dies, it might make the local news. This inequality of value puts meritocracy fundamentally out of touch with deep equality, and many of the most glaring elements of the culture wars represent attempts to ‘work around’ this disconnect.

Rather than being equally sacred, citizens of meritocracies are provided supposedly equal chances to prove their merits. To understand how merit is shown, we must understand the concept of merit. Merit is basically the ability to turn opportunities into valued outcomes. Merit can be broken down into: talents, which are the abilities given to us by nature or God; and character, which is shown by how we apply talents to the opportunities presented and produce (valued) outcomes.(20) So talent and character together are seen as the merit of a person. Together with equality of opportunity, these ideas form the intellectual infrastructure that our meritocratic society uses to decide important questions: who has earned the ability to go to college, get paid highly, and have their opinions respected?; whose merits have not been allowed to shine through because of low opportunities?

The identification of persons of merit, or as King termed it, ‘bright stars in the human firmament’, does not have to violate deep equality because it could simply be a means for deciding how society should divide labour and devote its resources for the greatest collective benefit. Think of the choices made by families who cannot provide all of their children with as much schooling as they might like. Such families often pick one person, based on their merits, to invest in. The ‘gifted’ sibling understands that their schooling was provided in the spirit of community and is expected to reciprocate. But ‘bright stars’ egos want the pride that can accompany such merit and to rub elbows with other stars.

So merit becomes status, and assessments of merit become disputes over status and privilege.

It is doubtful that a meritocracy that gives in to status-consciousness can live up to its own values. If those who receive privileges, earned or not, follow their egoic impulses, they quickly lose their sense of obligation and gratitude to others, especially if they become socially distant from those others. Meritocracy encourages us to bathe in the warm glow of pride that comes with the story that we did it ourselves, and so meritocracies become run by high-achievers who want to think of themselves as self-made (and pay low taxes and give their friends and relatives jobs). The narrowest interests of people already at the top are not served by ensuring equality of opportunity, but by insisting that meritocracy is functioning justly,(21) so that all positions are deserved, including the positions of the poor. No conspiracy of the powerful is necessary to create an inflated sense of meritocracy; the powerful will do it by virtue of their amplified influence and by having the same kind of vanity that everybody else has.

The word privilege itself is emblematic of a growing feeling that meritocratic society has indeed lost the ability to spread opportunities equally, so that outcomes are a poor guide to merits. Until recent- ly, the word privilege referred to outcomes that were considered earned or merited ─ an ability earned by gifted and enterprising people. The activist Peggy McIntosh(22) famously wrote in 1988 that she found that, as a white person, she carried a knapsack full of desirable but unearned privileges. McIntosh’s phrase became viral because it challenged an older narrative in which society tries to provide all people with rights, but these are taken away by rebellious racists that good people deeply oppose. Calling inequalities in opportunities ‘privileges’ implies that our supposedly meritocratic society hands out opportunities according to the prejudices of the powerful, and those who accept the status quo participate in this inequality. This idea is so influential that the word privilege has actually come to mean ‘unearned privilege’, an ability which is given to a person for reasons having nothing to do with merit.

The dissonance between meritocracy’s alluring promises of equality, and the reality of arbitrary and unequal allocation of value to people, means that efforts to correct inequalities of opportunity are necessary. Otherwise society will end up ‘rotting or exploding’ from the pressure of ‘dreams deferred’ as Langston Hughes put it.(23) Such work is a contribution to society, and a paradoxical status symbol: by standing up for equality more forcefully than others, individuals can prove themselves greater than others in moral character and therefore status. This impulse is by no means specific to left wing demonstrators. Widespread open disdain by US northerners for US southerners, who are historically associated with slavery and racism, has long been popular as a way to show moral superiority. These feelings have consequences – relationship psychologists find that disdain is the single greatest predictor of relationship failure,(24) and the state of today’s politics could be predicted from the disdain that was shown in yesterday’s moral conversations.

It shows that something precious can be lost in the rush to support equality when one sees that the lives of those who oppose equality can be proudly stripped of their inherent value. To take an extreme case, I remember watching the movie Django Unchained, about a former slave who kills his former captors in a gruesome manner; listening to the crowd cheer the death of slaveholders, and feeling the invitation to indulge in the cheap elevation of dehumanising the dehumanisers. I felt extraordinarily empty, as did my girlfriend at the time, who is black, and our conversations afterwards set me reflecting more deeply on the subjects in this essay.

To be clear, I am not saying that advocates for social justice, or their critics, are ‘really angry narcissists’ in disguise. Social justice advocates, like anybody else, can both care deeply about treating people like full members of the human family and sometimes bask in personal glory or superiority at the same time. The sight of egotism loudly masquerading as appreciation of sacredness can cause people to question whether there is anything but vanity, but this judgement, however understandable, is born of the same punishing instinct that denies our connection to deep equality generally (discussed above). The most absurd elements in ‘wokeism’ come from trying to express human impulses towards equality inside the intellectualised morality of a culture driven by status.

This shows most clearly in culture war attempts to correct inequalities of privileges and status due to historical discrimination. As mentioned, justice in meritocracy involves giving people status or value, according to their merits. This may not respect our deep equality, but it is a given in our society. It is natural to correct misperceptions that merit is reflected in ‘objective’ outcomes (income, job titles, twitter followers) that often result from inequalities of opportunity. So, underprivileged people, with few opportunities, have greater merits than their accomplishments show, and justice can be restored by correcting people’s status accordingly. Being the victim of oppression comes to be a kind of concealed merit, while privilege is a demerit, or even sort of a sin – at least in circles where systemic injustice is taken for granted.

Privileged people do not easily volunteer for downward changes in status though, so somebody has to inform them of their social demotion, often quite bluntly. Immense pride in taking on this responsibility to restore justice can develop, and even become a sort of class interest, which will tend to be protected just like any egoic pleasure. I don’t deny that this ‘solution’ can be intensely ugly, but I ask that the reader notice that it makes a lot of sense within our moral system. If we want to be free of this dynamic, a deep change in mindset is necessary.

Another layer of unpleasantness comes because few people want to surrender status and so few admit their superior opportunities. It is helpful, then, to come up with some simple and clear ideas about who deserves more, or less, status. Because humans are organised in groups, group membership helps us make pretty good guesses at others’ privileges. If these generalisations were totally accurate, they would allow us to totally correct unjust inequalities in status, and to feel totally good about being the agents of change, so there can be a tendency to see such generalisations as truer than they are. But where the resulting picture of privilege, and thus, efforts at demotion, are flawed, massive resentment arises. For example, there has been backlash against ideas of white privilege by white people who didn’t grow up with much money and weren’t invited to a nice university, and who see the idea as erasing their own very real hardships.

The tension between meritocracy’s method of measuring of human value and its insistence on equal opportunity are most clear in discussions of talent. Though we often say that ‘everybody is equal’, talent means that people do not have equal chances to become valued within meritocracy, and would not, even if we wiped away all sources of unearned privilege. One popular way of dealing with this unpleasantness is by not discussing differences in valuable abilities (talent) except when they are made glaringly obvious, making people equal in talents and therefore meritocratic status.(25) For example, we can’t deny the existence of size and its importance for some sports.

But there is greater denial around more intangible talents such as differences in intelligence, athleticism, and charisma. These are often denied, and dwelling on them is resisted with an attitude that is unpleasant enough to get people to change the subject. Still, we all grow up in classes where some kids are much better than others at physical contests like sports, and some are much faster or better at answering the hard questions, and some gravitate towards leadership, and all important production requires that we use these talents.

If the awkward issue of talent is raised out loud, usually somebody will try to save the equality of value by saying something like, ‘being less talented just means that you need to work harder’. But one cannot erase deficits of talent with hard work, because people with talent can also work hard. Another way of resolving the problems posed by talent is to insist that, overall, people’s talents must somehow be equal (so the smart must be socially awkward, and the athletic must be stupid, etc.). No such thing has ever been shown, but it is often assumed, because this would imply that we had ‘equal chances to be valued’(26) within meritocracy, which would be nice.

The idea of talent presents a further problem because it can be used as a weapon to justify inequalities in outcomes and status that are actually due to sheer prejudice. For example, racism and sexism are essentially justifications of historical inequalities in treatment that are built around supposed inequalities in talent. The most absurd forms of racism and sexism usually acknowledge that people’s lives are equally sacred, but that, at the same time, claim that oppressed groups are unequal in abilities and so should not be allowed to run their own lives (like permanent children). This stubborn, subtle and cruel creativity in justifying prejudice has inspired tactics to prevent these prejudices from being expressed.

The final culture war tactic that I’ll discuss, ‘Political correctness’ refers, basically, to a group of intellectual strategies that short-circuit people’s attempts to verbally express or justify their own inherited sense of superiority, and thereby preserve both deep and surface equality. The most common PC tactics are norms of speech that prevent speech acts that could imply an inequality of value across groups. I believe it is important to discuss these tactics given the acrimony around their most extreme forms. I admit that there are tactics that some might call ‘PC’, such as objecting to sexist ‘codewords’ (e.g. calling women ‘bossy’) which are useful. I note, though, that PC tactics try to defend equality by a rule-based marking out of acceptable speech acts (outward expressions) rather than emphasising deeper engagement. It would be a stretch to dismiss all PC tactics as misguided, my point is that they are within secular society’s comfort zone, and are a surface level response that stifle inherited senses of supremacy.

An extreme on-the-street PC solution, endorsed officially nowhere, but seen often, is to put barriers in the way of people talking about differences between groups on any dimension, other than their historical privileges. In practice, we cannot talk about eight billion humans without generalising, yet a hallmark of PC strategies for social justice is to claim ‘you can’t generalise’. This statement is quite selectively made when somebody attempts to make a generalisation about a protected group. Taken to its extreme, this denial assumes protected groups are equal in all traits to other humans, and thus establishes a logical claim that protected groups are unquestionably equal with others in merits (character and talent) under any conception of what merits are, even the most eurocentric, patriarchal, or xenophobic.

A notable example of such dynamics concerns women. There is increasing resistance to all sorts of generalisations about women that many women freely make (that they are shorter and less physically strong than men, spend more money on make-up, like shopping, are generally better cooks than men, are more interested in people, more drawn to children and so on). These generalisations are of varying accuracy but it is very important to some advocates of equality to dispute all of them and to prove that all but the most undeniable differences are due to the social environment so that, really, genders are truly equal in traits. Scientists who’ve studied the evidence about differences between genders also disagree dramatically about their conclusions,(27)(28)(29)(30) yet many who’ve done little research are sure that belief in such differences is inherently sexist.

This leads to countless instances of abrupt silencing of others’ opinions that have become staples of the caricature of the liberal left that many love to despise, not least supporters of Donald Trump and

Fox News. In the end, I feel this dynamic often obstructs the as yet incomplete uprooting of sexist and racist attitudes; it is rather like placing a rock over the roots of a weed. The weed is simply left in the dark, and one day will grow its way out into the open.

Where prohibitions of generalisation become most burdensome is their prohibition of mentioning even cultural, stylistic differences. Banning the mention of stylistic differences removes the space for resourceful racist impulses to justify or express themselves, but also for reasonable, good faith discussions of cultural difference. So, for example, weird claims that, some group’s diet is evidence of its inferiority may be eliminated, but in the same motion suggesting that black Americans or gay men generally speak with a different accent than straight white Americans is rendered a taboo behaviour because this might allow some kind of subtle mockery. So many differences have become largely taboo to discuss except for comedians like Dave Chapelle,(31) George Carlin(32) or Triumph the Insult Comic Dog.(33)

The impulse under the ‘PC’ tactic of short-circuiting discrimination by disputing generalisation has a certain kind of nobility to it, but also some dishonesty and hubris. The noble goal is easy to understand. This conversation is perhaps most alarmingly dishonest when it attempts to ban generalisations about stigmatised groups by claiming that generalisations aren’t possible, when obviously little is possible in life without generalisations.

This selective ban on generalisation risks becoming a sign of class hubris because it often amounts to a decision by one class of people (educated and liberal) about what types of generalisations can be entertained by whom. Of course nobody can avoid committing the invented sin of generalisation with every sentence. For terms such as male, white, Italian or French to mean anything, we must be able to generalise, somehow (French people must have distinguishing traits for ‘frenchness’ to be worth mentioning). Prohibiting discussions by invoking reasons that are obviously not true (such as that no generalisations can be true) is basically a display of arbitrary authority. It is the ability to feel entitled to do this that makes PC language an ‘elite’ activity in the eyes of many.(34)

The obvious alternative is constant vigilance in how we hold generalisations, asking whether they are valid, and noticing what we make them mean. Our ability for abstraction must be used wisely but there is no argumentative formula for halting desire to be superior to others. Judicious generalisation is what the use of our gift or reason always implies, and the assertion that others cannot be trusted to reason cuts dangerously close to disdain.

The excesses of PC tactics unfortunately have had few serious opponents among those on the left of the political spectrum until recently. PC might be ugly, we have said to ourselves, but it is all for the best: after all, a politically correct ban on generalisation will stop people from dreaming up elaborate new justifications for discrimination. Or so we hoped.

Of course, the election of Donald Trump and a host of nationalist leaders was the nature of reality showing through. It revealed what many expected but could not prove. Political correctness has not done away with racism, but only made it taboo to express. Jordan Peterson’s meteoric rise from an obscure academic to international celebrity showed a growing taste for credible-seeming defenses of claims that are perceived as ‘un-PC’ such as Peterson’s contention that, as a group, women show less interest in science and technology jobs. The liberal elite, which is, for its critics, virtually identified by its use of disdainful rhetoric, was Trump’s favourite target and continues to be that of his followers. The overstep in power represented by the most extreme PC dynamics has long since become a liability to the quest of creating a society that treats all people as equally sacred.

***

Despite the fact that the need for more effective politics is never far from my mind, optimism about humans’ ability to appreciate each other’s equal sacredness was my greatest motivation for writing this essay. The benefits are easy to agree on for anybody who admits there is sacredness to appreciate: a society attuned to sacredness would reject status and accord the same respect to people by police officers and to janitors and food service workers as to presidents, and provide (truly) equal chances to build a home. The dream of a world that judges people not ‘by the color of their skin (or their gender, sexuality or any other such trait) but by the content of their character’, has replaced economic growth and scientific advance as the one thing that all progressives agree on as progress. I am optimistic that when we have the courage to see that we will not get there with more of the same, we will try something else.

I don’t offer deep equality, though, as a spiritual ribbon with which to neatly tie up the mess we’re in. Deep equality will not solve the problems of meritocracy or the West. To the extent we see deep equality, we have a capacity to see one another’s joy and suffering clearly enough to sense what our collective problems are. The journey to insight into deep equality has never been easy, though, and mass flashes of spiritual insight have been discussed but never seen, so I doubt if humans will ever be so keenly attuned to one another’s sacredness that laws become unnecessary. We may need many new laws and even a new economic system. I am more interested in making the case that appreciation of deep equality is possible, can be cultivated, and is not external to our political economy. What troubles us about the culture war stems in large part from indulgence in secularist notions that we can depend on ideas of equality without emphasising felt connection to their ultimate basis.

The stakes involved in loosening the hold of the equality complex are high. The ecological crisis stands to be tragically unequal in its consequences and the potential scale of injustice will become more triggering as climate change progresses. Yet, negotiating a path forward will require sustained interaction between proud egotistical countries that will retain unequal amounts of power. I don’t see how any collective negotiation of this maze of tradeoffs can happen without compassion and elevated willingness to see each other’s value. This is especially true of the privileged who will have to impose vast costs on themselves. Climate action will likely be more challenging than recent successes in curbing police violence and recognising transgender rights. It will probably require that we both write new laws and rules, and work to become the people who can adopt such rules and laws.

Much of what I’ve discussed might, by many, be considered impractical, ‘abstract’ mysticism. Abstraction is a name for what we cannot ground in experience, and for a culture with little spiritual practice, compassionate and love-based approaches will be abstract. However, nobody who has actually had a long-standing spiritual practice has told me that deep equality, compassion and their power for transformation are in any way abstract and that these ideas are abstract and exotic in a few places in the world, which, I have argued, now need them most.

The idea of reason-driven secularity spread generations ago, as Protestants and Catholics were killing each other in part because they disagreed about the kind of lives that their spiritual traditions, all of which advocated love, called them to live. Lest we be too skeptical of our wisdom traditions, we should remember that secularity worked by trying to adopt statements on which spiritual communities could agree into a rational system of morality that was not at the behest of any wisdom tradition. It created a common space free from religion, leaving spirituality or ‘soul-craft’ to the sphere of the private, ‘inner’ life, and practical matters to rationality and science. As history, science and thought have ‘progressed’, the West’s wisdom traditions have frayed for lack of public discussion on the eternal tensions between power, ego and morality, and how to approach them now, in a brave new world.

The mindfulness movement has emerged partly in response to this gap, forcing people to reconsider what the boundaries of secularity are. This has, at times, struck people as off-putting precisely because it does not broach morality deeply enough.(35) Part of the answer, as argued in my recent book with Perspectiva, is to take such ‘secular’ spiritual practices further. We have to ask harder questions about what collective efforts to prepare ourselves ‘inwardly’ for the future look like. If secular norms prohibit deep equality from being part of this conversation, then the secularity complex may need to be the next cultural supposition that we question.

Liam Kavanagh is director of research at Life Itself, a community for those working at cultural borders of secularity and spirituality. He draws on contemplative, intellectual, and collective wisdom practices to mediate the tensions that immobilise cultural imagination, allowing new visions for collective flourishing to emerge. His academic graduate research interests as a cognitive scientist were in human mimicry and embodied cognition, and he is currently pursuing research and applied work in collective wisdom, with an emphasis on applied research projects that address the role of Western Ideology in mounting social dysfunction. Find out more here.

You can follow Perspectiva on Twitter & subscribe to our YouTube channel.

Subscribe to our newsletter via the form below to receive updates on publications, events, new videos, and more…

Perspectiva is registered in England and Wales as: Perspectives on Systems, Souls and Society (1170492). Our charitable aims are: ‘To advance the education of the public in general, particularly amongst thought leaders in the public realm on the subject of the relationships between complex global challenges and the inner lives of human beings, and how these relationships play out in society; and to promote research, activities and discourse for the public benefit in these subjects and to publish useful results’. Aside from modest income from books and events, all our income comes from donations from philanthropic trusts and foundations and further donations are therefore welcome. Please consider donating via the button below, or via Patreon.

Endnotes

1 For a survey and synthesis of several useful ways of intellectually understanding sacredness, as best as we can see: Rowson, Jonathan, Spiritualise: Cultivating spirituality sensibility to address 21st century challenges (2nd edition) Perspectiva/The Royal Society of Arts, 2017. https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/pdfs/reports/spiritualise-2nd- edition-report.pdf

2 Lynch, G, After Religion: ‘Generation X’ and the Search for Meaning, Longman & Todd Ltd, 2002, p.11.

3 https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/american- dream-sermon-delivered-ebenezer-baptist-church

4 Merton, T, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, 2009, Image.

5 See Thich Nhat Hanh: ‘The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching.’

6 The declaration of human rights promises: ‘recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family’ (Ishay 1997: 407, italics mine).

7 Rawls, John, & E. Kelly (ed.) Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

8 See for example: Siedentop, L, Inventing the Individual, Harvard University Press, 2014, or Gray, John, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals, 2016, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

9 Campbell, Joseph, & Moyers, Bill, The Power of Myth. NY: Doubleday, 1988.

10 McGilchrist, I. (2018). Ways of attending: How our divided brain constructs the world. Routledge.

11 McGilchrist, I, The Master and His Emissary, 2009, Yale University Press.

12 See for example C.J, Werleman’s reporting on silence about the current Uighur genocide. https://bylinetimes.com/2021/03/29/why- does-the-anti-imperial-left-so-often-end-up-denying-genocide/, https:// bylinetimes.com/2021/07/16/the-hypocrisy-is-overwhelming-former- nba-player-royce-white-slams-industry-for-deafening-silence-on-uyghur- genocide/

13 The Combahee River Collective, The Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977. See: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american- history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977/

14 To take an example, Jair Bolsonaro, who many on the political left see as the epitome of the privileged, toxic white male, is the leader of a majority non-white country, showing that the appeal of such leadership style can be extended past the demographics that it favors within the West.

15 This seems to happen in part because currently privileged people sometimes use the fact that their ancestors were oppressed to avoid a feeling of responsibility for addressing oppression now.

16 Nietzsche, F. W., & Hollingdale, R. J, On the Genealogy of Morals,1989, Vintage.

17 The use of priests as agents of colonial rule by European empires and popes with armies of underage sexual servants provide a few colorful examples.

18 Some readers may ask why status is not taboo while power is. The simple explanation is that power itself cannot be explained as a contribution, whereas the pursuit of status and power usually involves helping to produce something that people want (from computers, to legislation) which can at least be claimed to be a contribution to society.

19 For an extended discussion of this dynamic and how it creates anxiety about accomplishments, see De Botton, A, Status Anxiety, 2008, Vintage.

20 For further discussion of these categories and evidence about whether meritocracy is practically achieved see: McNamee, S.J. & Miller, R.K, The Meritocracy Myth, 2009, Rowman & Littlefield.

21 See again McNamee & Miller for discussion of the mythologising of meritocracy.

22 McIntosh, P, ‘White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies’, Working paper No. 189, Wellesley Center for Research on Women, 1988.

23 Montage of a Dream Deferred, In: Rampersad, Arnold. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1995. p. 387. Online at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46548/harlem

24 See, for example, Gottman, J.M, Gottman Method Couple Therapy. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy, 2008, 4(8), 138–164.

25 Note that it is meaningful talent we worry about; an ability to roll the tongue or double-jointedness are not necessary to avoid talking about because these offend nobody’s sense of self-worth.

26 I do not believe that it makes sense to claim that humans truly have something called value, though they are evaluated by others, based on the pleasures their work and thought produces.

27 For two researchers who think male and female brains are very different see: Baron-Cohen, Sascha, The essential difference: Male and female brains and the truth about autism, Basic Books and Brizendine, 2009, & Brizendine, Louann, The Female Brain, Broadway Books, 2006.

28 For a review of Brizendine by a woman’s studies scholar

and a neuroscientist see: Young, Rebecca. and Balaban, Evan. Psychoneuroindoctrinology. Nature 443, 634, 2006: https://www.nature.com/ articles/443634a

29 For a researcher who thinks female and male brains are hardly different at all see: Rippon, Gina, The Gendered Brain: The new neuroscience that shatters the myth of the female brain, Random House, 2019.

30 For a review of Gina Rippon’s book by a neuroscientist, see: Cahill, Larry ‘Denying the Neuroscience of Sex Differences’, Quillette, March 29, 2019 Online at: https://quillette.com/2019/03/29/denying-the-neuroscience-of- sex-differences/

31 E.g. Sticks and Stones https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sticks_%26_ Stones_(film)

32 E.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9n8Xp8DWf8

33 E.g. Triumph the Insult Comic Dog Talks to Young Voters: https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=j556MWGVVqI

34 I note that this point is rapidly becoming dated, as I hear more and more that we will soon live in ‘a world without labels’. A world without labels and expectations is the only one in which where nobody would not labor under false.

35 For a great discussion of how we might do some of this necessary work, I recommend Larry Ward’s book: America’s Racial Karma.