Jonathan Rowson

May 26th, 2021

The following essay is an adapted version of the preface to the book Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and emergence in metamodernity, published by Perspectiva Press.

Read & download the essay as a PDF here: Metamodernism and the Perception of Context- The Cultural Between, the Political After and the Mystic Beyond

The full essay is also available to read below.

Metamodernism and the Perception of Context

The Cultural Between, the Political After and the Mystic Beyond[1]

by Jonathan Rowson

Metamodernism is a feeling, and all that constitutes the feeling and flows from it. When we consider the mystery of consciousness and the human drama playing out on this charming anomaly of a planet, feelings are far from trivial – they have cosmological significance. The metamodern feeling co-arises through the perception of our context writ large; it is aesthetic in nature, epistemic in function, historical in character, and it serves to call into question the purpose of the world as we find it, and the meaning of life as we know it.[2]

If, dear reader, you do not feel called upon to read further, to try to understand more fully what metamodernism means, I cannot blame you, and even envy you a little. Life is short, there is work to do, and we cannot dance with every ism that gives us the eye. To paraphrase from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, some are born into metamodernity, some become metamodern and some have metamodernism thrust upon them. I am mostly in the latter camp. I didn’t seek out this – whatever it is – word, concept, ideology, pattern, movement, structure of feeling, state, stage, sensibility, episteme, movement, idea, notion, yet somehow metamodernism found me. I have used the term in my writing periodically, I have been called a metamodernist, and I have editorial responsibility for publishing a Perspectiva anthology of writing informed by metamodernism: Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and emergence in metamodernity. As one of its many adoptive parents, I notice that I feel responsible for metamodernism, and hope to help it mature in some way.

It is easily assumed or inferred that metamodernism emerges from within the early 21st century internet-infused cultural epoch of metamodernity, but the relationship between the two terms is more interesting than that.[3] While the meaning of the term modern is notoriously contested, few doubt the validity of the idea of modernity as a grand epoch as such (more below) nor that we are now in the latter stages of it and in some sense moving beyond postmodernity, or trying to, but what we should call this phase is contested, and is mostly a matter of choice of perceptual framing. The other contenders like hypermodernity, supermodernity and even ecomodernity all focus directly on the implications of technological developments. The meta prefix is distinctive, however, because it is generatively reflexive and tacitly humanistic. One way to grasp the value of the idea of metamodernity is to say it’s about focusing our attention on our subjective and inter-subjective relationship to these times we live in, when we stand, in some quaveringly uncertain sense, after, within, between or beyond modernity.[4]

I believe the point of invoking metamodernity is not to insist on this name for a chronological phase of time but to resolve to characterise a cultural epoch with a Kairological quality of time. What this approach discloses is not just that it’s simply the early 21st century but that it’s in some meaningful sense the time, more precisely perhaps our time, to look within, between and beyond. It is time to reappraise our inner lives and relationships by grappling with the apparent spiritual and material exhaustion of what has passed as normal and normative for a little too long: the presumed progress of science, reason, bureaucracy and industrial capitalism, the limitations of perspective and the failure of critique. We are now obliged to create meaning and fashion agency within the context of meta-crises of perception and understanding relating to ecological, social and institutional breakdown, where one world seems to be dying, and another is trying to be born. The point of metamodernism is therefore to help us better perceive our historical context by developing theories and practices that allow us to feel into what it means to be in a time between worlds, where meta-crises relating to meaning and perception abound and we struggle to perceive clearly who we are and what we might do; where meta-theories seem friendly because mere theory feels absurdly specific; where nostalgic longing feels like it is as much about the future as the past, and where we sometimes feel like being ridiculously romantic and romantically ridiculous. To be metamodern is to be caught up in the co-arising of hope and despair, credulity and incredulity, progress and peril, agency and apathy, life and death. I had mixed feelings about metamodernism until I realised it is about mixed feelings.

The perception of context

What is at stake here is how the perception of context shapes the world. Over the last quarter of a century we have been scrambling to find language forms to help us catch up with what our shifting sense of context means for who we are, and how we should live. For many millions of people, cultural and technological developments have outpaced our conceptual grasp of them. Whether it is the sight of huge swathes of Australia on fire, the miasma of misinformation on so-called phones that have commandeered human eyes and hands, or the world apparently brought to its knees by a wayward bat in Wuhan; we are struggling to grok what is happening. In light of that ambient confusion, we seem to face what Graham Leicester and Maureen O’Hara call ‘a conceptual emergency’.[5] We struggle to perceive our contexts clearly enough to be confident in our theories and actions; and since the perception of context is a dynamic variable within and between people, and also a generative capacity in any normative vision for the world, a case arises for concepts that help us to perceive context better.[6]

The challenge is that in a digitalised, ecologically compromised and politically charged world, where hyper-objects abound, context writ large is impossible to perceive precisely or even accurately.[7] At the planetary scale, contexts are myriad, layered, contested, incommensurate and cross-pollinating, and our perceptual apparatus is often overwhelmed, if not deliberately distorted by meditating influences. In such a world there can be no conceptual panaceas, so we have to make do with our best available approximations. Meaning-making animals that we are, we hide our confusion under capacious conceptual canopies such as modernism, postmodernism and metamodernism, and by taking shelter there we allay our sense of feeling completely lost. While the use of such clunky terms is not always edifying, it is forgivable, and for some purposes, necessary. Just as we like to know the name of a person after talking to them for a while, but still don’t pretend to really know them, it is natural to seek to name the cultural and historical context we are living through, and to try to discern a telos for ourselves and others within it. This inclination is especially true when we sense that our place, our telos, our entelechy, may not be in this world as such, but somehow meta: after, within, between or beyond it.

The point of grappling with metamodernism, then, is not about passive conceptual nourishment but is rather a way of taking intellectual and moral responsibility for the critical active ingredient in play – the perception of context in our lives and our times. I feel the question worth asking is not really what does metamodernism mean – which presupposes that people can care, do care or should care. More profoundly, I want to understand: What distinct perceptions of context does the notion of metamodernism elicit, disclose and support, such that it might be worthy of our attention?

I hope to show the following: first, while metamodernism has divergent interpretations, it functions as an orienting theory to describe (and, for some, prescribe) our relationship (which is in some sense meta) to the cultural and historical context of late (post)modernity. In this role, metamodernism is coherent, rich, illuminating and challenging enough to help us orient ourselves towards context writ large – a context that has shifted abruptly in this century through technological developments and ecological collapse, and now poses an existential test in terms of human understanding and cooperation. Second, modernism and postmodernism have their own capacious dignity, and both live on with us. The distinctiveness of metamodernism is often hard to discern, but that distinctive meaning can be teased out in a way that is generative, and the personal work involved in the teasing-out is part of its value. Third, metamodernism has more than one genesis story and is in every sense diverse in its origins; it is as much about protecting human dignity and interiority from the techno-capitalist dystopias of hypermodernism as it is about the particularly funky relationship between modernism and postmodernism. Fourth, metamodernism is grounded in the importance of aesthetic understanding as a form of epistemic orientation. The structure of feeling at the heart of it – whether described as neo-romantic, post-tragic or otherwise, is not background music but the active ingredient itself. Fifth, Hanzi Freinacht’s contribution to metamodernism is substantial but controversial, and it is primarily about the shift in register from theory to meta-theory, thereby effectively historicising Integral Theory and politicising the metamodern sensibility. Sixth, while Hanzi helpfully distinguishes six different ways in which metamodernism is used(see below) the question of what exactly metamodernism is remains somewhat moot. For instance, it is an open question to what extent the impetus that drives developmental metamodernism is orthogonal or even antithetical to the aesthetic understanding of cultural metamodernism. Seventh, the cross-currents of metamodernism can perhaps best be distilled into three main patterns: the cultural between, the political after and the mystic beyond. Eighth, most attention has been focused on the former two, but an engagement with metamodern metaphysics is a new frontier. Ninth, while metamodernism remains variegated, I suggest the perception of context it offers can be distilled into four main themes corresponding to each of the four integral quadrants: interiority, intimacy, ecology and historicity, all of which are in some sense developing. Tenth, and – mercifully – finally, the broad, elusive and contested nature of metamodernism will remain; this is not a sign of weakness, but precisely what we would expect for a conceptual holding pattern of context writ large in a time between worlds. All other things considered, I contend that when viewed as a whole, metamodernism has its own coherence, dignity, relevance and timely generativity.

Modernism and postmodernism as dysfunctional but loveable parents

We cannot hope to make friends with metamodernism if we are going to caricature or patronise her parents. We need to understand the relationship between Mr Modernism and Mrs Postmodernism well enough to enjoy gossiping about it (there is a significant age gap for a start …). Part of the challenge is that there are so many modernisms and postmodernisms that it is not surprising metamodernism is a wayward child, taking some time to find itself. And we see the same tensions between cultural, literary and political expressions of modernism and postmodernism in metamodernism today, which suggests this is a feature and not a bug of any catch-all term for the perception of context writ large. Making exhaustive sense of these conceptual thickets calls for an elaborate scholarly performance to disclose the multiple meanings of modern/ity/ism and postmodern/ity/ism and reflections on their interpretations and relationships, while also giving a respectful nod to wayward cousins like hypermodernity, altermodernity and so forth. Mercifully, many others have tried to do that work for us already. What follows is based on a conscientious reading of the relevant literature, but my aim is less an academic exegesis than an attempt to share my process of forming a relationship with metamodernism, to help the reader forge their own.[8]

The term ‘modern’ is derived from the Latin modo and simply means ‘of today’, distinguishing whatever is contemporary from earlier times. Modernity refers to our contemporary civilisation built over the last 400 years or so through scientific, industrial and technological revolutions, but what makes modernity is not just method or machines. We are not, as sociologist Peter Berger puts it, ancient Egyptians in airplanes, not least because so many of us are future-oriented, at least in our younger years. Indeed Habermas’s description of modernity is precisely about that. In The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, he writes: ‘the concept of modernity expresses the conviction that the future has already begun: it is the epoch that lives for the future, that opens itself up to the novelty of the future.’ As we open up to the future, and as the world changes, we change too. And so modernism, although voluminous and outrageously ambiguous, refers to the worldviews that arose from human culture stewing in the juices of modernity for decades. Modernism expressed itself in art, architecture and literature and evolved into political institutions and ideologies. Science is quintessentially modern but capitalism and communism are also modernist endeavours, and so is the organised aspect of religion and human rights law. Perhaps most relevant for current purposes is that modernism entails an irresolute process of secularisation and also the growth of civic and commercial institutions powered by bureaucratic and instrumental rationality and an exploitative relationship to nature. Modernism is therefore about presumed material and scientific progress, but it is often accused of wearing blinkers about its collateral damage. For instance colonialism, slavery and fossil fuels drove much of modernism’s so-called ‘progress’. In a related sense, in Habermas’s later work, Modernity: An Unfinished Project, he argues that modernity is characterised by the separation of truth, beauty and goodness; of science, art and morality. That separation of our value spheres was a source of fragmentation and alienation that lived on in postmodernism, and part of the purpose of metamodern metaphysics mentioned below is to somehow bring them back together.[9]

Like modernism, postmodernism is polyform and enigmatic. Some see the very idea of summarising as antithetical to the reflex pluralism, perspective-taking and reactivity of postmodernism, such that any definition of postmodernism can be seen as performative contradiction. However, one defining quality of postmodernism is that it is modernism turned in on itself: the tools of reason questioning their own reasonableness; the idea of progress noticing, as a kind of progress, that it is indeed an idea. This spirit of recursive awareness is present in the emphasis on the relationship between knowledge and power and social (de)construction of reality rather than its simple presentation; presumptions of depth and origin and authenticity are questioned, and there is even some revelling in superficiality as its own kind of profundity. With postmodernism there is an emphasis on plurality rather than unity, and a preference for the experienced immanence of life over its putative transcendence. However, these are matters of disposition and emphasis, course corrections for modernism that, yes, sometimes entail over-corrections, but they are not typically doctrinal in nature, yet are often misunderstood as such. This refrain makes more sense when we grasp that postmodernism arises within a relatively short time frame. Some see Nietzsche as a kind of postmodern prophet writing before the 20th century; for instance, in Twilight of the Idols he noted that the ‘will to a system lacks integrity’, which anticipates perhaps the signature postmodern line of Jean-François Lyotard in The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge in 1979, namely that the postmodern condition is characterised by ‘incredulity towards metanarratives’.[10] Yet, as always, Nietzsche is sui generis; it wasn’t until the sixties counter-culture that postmodern vibes start to tingle from the sprouting San Franciscan flowers, the spirit of norm-breaking, self-discovery through oppositional identities (e.g. anti-Vietnam war) and the challenge to hierarchical and conventional power structures. That spirit lives on in today’s ‘identity politics’. However, my impression is that what Jeremy Gilbert calls ‘the long nineties’ may be the best temporal locus for the postmodern sensibility, especially if we allow it to be so long that it sneakily includes some of the seventies, eighties and noughties too. That quarter of a century or so before and around 2000 is when disquisitions about key postmodern thinkers (who were saying very different things and often didn’t identify as postmodern) like Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Richard Rorty, Donna Haraway, Frederic Jameson and Jean Baudrillard were at their height. This was also a time of the Cold War coming to a gradual end, when one side appeared to win the ideological battle, and for a time global politics felt relatively stable. In the pre-internet calm, and before climate collapse seemed credible, millions were at peace with their modernist gizmos – microwaves, washing machines, televisions – and yet some restless ironic detachment was setting in. The American rock band Talking Heads, formed in 1975, were quintessentially postmodern; they sang about their beautiful house not being their beautiful house after all, their lyrics observing moments of realisation that our lives are often a dream created for us rather than by us. Meanwhile, Hue and Cry sang about not needing ‘…your ministrations, your bad determinations’ and having had enough of the ‘pseudo-satisfaction’ on offer.[11] And yet still, and even for some years later, we could go to the movies to distract ourselves with Pulp Fiction (1994) and Fight Club (1999), films that did not pretend to be deep but spoke to us by highlighting our misplaced sense of narrative coherence. When all that was too much, we could chill at home and watch simulated realities in Friends or Seinfeld or The Simpsons; and we could laugh along because while we were still grappling with the human condition, and there were still problems outside, everything felt more or less under control.

That is not today’s world of course. Postmodernism, though still relevant and pervasive, does not feel adequate to our species-specific task of survival or renewal at scale in the context of ecological peril in particular, and the context that gives rise to it: the meta challenge of saving civilisation from itself.

Origin stories and forgotten prophets

Metamodernism began ripening in the early 21st century onwards, but it has a meaningful pre-history that should not be overlooked. The term was first mentioned by American literary scholar Zavarzadeh Mas’ud in 1975,[12] to describe patterns of aesthetics and attitudes that he had been observing since the 1950s, including the co-presence of fact and fiction, art and reality, manifest most tangibly in the hybrid genre of ‘the nonfiction novel’. Those who know his work inform me that since he was writing before the term postmodern was in wide circulation, Zavarzadeh may have been using meta in the most straightforward sense of ‘after’, synonymous with ‘post’. This would help explain why metamodernism took a while to get into its stride, and beyond the occasional reference in literary journals, there were perhaps only two important but somewhat neglected sources in the nineties inspired by liberation theology – Albert Borgmann and Justo L. Gonzalez – recently uncovered by Brent Cooper. These sources point to a broader (and perhaps deeper) origin story about the provenance of metamodernism that challenges the academically orthodox view that it is primarily a literary or artistic affair.[13]

In the field of technology studies, Albert Borgmann (1992) juxtaposed hypermodernity with metamodernity in a way that clarifies the two incipient worlds that we live with today. One is a dystopian future we often feel we are drifting towards, while the other is the future we are called on to fight for. For Borgmann, postmodernity bifurcates into a runaway hyperreality where we become increasingly lost and exploited through technological servitude. He refers to ‘the fatal liabilities of the hypermodern condition, of a life that is enfeebled by hyperreality, fevered by hyperactivity, and disfranchised by hyperintelligence.’ And yet, if we can muster the courage, guile and coordination, we can instead create a world of metamodernity where humans reclaim control of the capacities required to shape our lives, through what Borgmann calls ‘focal attention’: ‘Focal things cannot be secured or procured, they can only be discovered, revered, and sustained in a focal practice. Such focal things and practices are well and alive in our artistic, athletic, and religious celebrations.’ Borgmann’s framing of the metamodern impulse is echoed in the challenges of addiction and attentional capture highlighted by the recent documentary The Social Dilemma, and also in Matthew Crawford’s applied philosophical work on the need for ‘focal activity’ and an ‘attentional commons’.[14]

Another figure largely ignored by the field of metamodern studies is Cuban-American liberation theologian Justo L. Gonzalez, who connected metamodernism to the postcolonial struggle in Metamodern Aliens in Postmodern Jerusalem (1996). Gonzalez sees a legitimate use for ‘meta’ in the sense of going beyond the modern, such that the enduring postcolonial struggle of many millions around the world is not subsumed within postmodern critique but grounded in a generative vision of reality in turn grounded in liberation from enduring colonialism in all its forms. Cooper suggests that Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez embodies Gonzalean metamodernism: ‘A young female minority leader of a new progressive coalition … Pragmatic idealism is back with a playful vengeance.’ [15]

Borgmann and Gonzales did not build their intellectual identities around metamodernism; they used the term almost incidentally in fairly obscure sources, and did not initiate discourse around metamodernism. Nonetheless, in their own ways Borgmann and Gonzalez exemplify an impulse that could be distinctly and meaningfully metamodern, namely the desire to disclose perceptions of context (meta as within and between) that are saturated with history, meaning and perspective (because modernism and postmodernism have done their work) but nonetheless remain ours to shape; and that perception of context is therefore potentially liberating (metamodern). While these sources uncovered by Cooper are not an explicit part of the conceptual scaffolding on which contemporary ‘metamodernism’ has been built, I am impressed by the fact that they both exemplify a perception of context that traverses political and spiritual features of human experience and proactively seek to combine them for normative ends. These sources speak to me because in my own way I have been trying to do similar work for the last decade, starting with the realisation, while working at The Royal Society of Arts in London, that my policy research work on climate change and my public enquiry into spirituality were grounded in the same perception of context.[16]

In what might playfully be called the mid-history of metamodernism, there is also an intriguing and underexplored relationship between metamodernism and Yoruba culture that is intimated by Moyo Okediji in the late nineties, the spirit of which can be discerned today in Bayo Akomolafe’s poetic and prophetic thought today, and which Minna Salami is currently researching for Perspectiva. Some have described Reggae music as inherently metamodern in its awareness of an interiority characterised by the co-presence of suffering and joy, which we can sense for instance in Bob Marley’s line about some people feeling the rain while others just get wet. More broadly, a case has been made for Black metamodernism.[17] Historic figures including Martin Luther King and contemporary figures like Cornel West are thought to exude the metamodern sensibility. For instance, when asked what to do about racism in news interviews, West often quotes Samuel Beckett: ‘Try again, fail again, fail better.’[18] I am not sure where one might begin to place the metamodern in South or East Asian culture, but Meta Modern Era by Shri Nirmala Devi gave a quasi-Vedantic spiritual conception of the idea in 1997,[19] and much of the paradoxical and playful nature of Taoism sometimes feels metamodern in spirit, even if the Chinese Communist Party does not.[20]

Discussions of the genealogy of metamodernism also draw attention to a range of socio-political developments that shifted the world beyond the postmodern into something qualitatively new and ideationally up for grabs. Seth Abramson has written widely on metamodernism and emphasises the advent of the internet as seismic and pivotal, changing our capacity for self-expression and collective sense-making as a key driver of metamodern sensibility.[21] Zachary Stein emphasises our reckoning with a shift in geological time through the dawning of the Anthropocene (and Jason Moore’s Capitalocene) in which humans discover they are unwitting agents of accelerating geological time.[22] The events of 9/11 and its aftermath have also been highlighted as the moment it became obvious that Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’ had ended, where history was recommencing with a vengeance with no obvious telos in sight.

A structure of feeling

This brisk genealogy of some major aspects of metamodernism is important because it shows that the term can be seen as variegated, expansive and cross-cultural in scope. However, it is also true that metamodernism only really started to get noticed and respected by a critical mass of discerning people when two young Dutch cultural theorists, Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, published Notes on Metamodernism in 2010 – responding mostly to cultural developments in the first decade of the 21st century. The V&vdA (a useful shorthand which I hope they’ll permit me) paper is commendably rich and detailed and well-illustrated with examples that disclose the ‘structure of feeling’ that characterises our metamodern predicament, including this signature line:

Ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity.[23]

Since the authors of these words are invoking ontology rather than just speaking figuratively, it is worth asking whether ‘oscillation’ is precisely the right term. ‘Juxtaposition’ (Seth Abramson) or ‘superimposition’ (Daniel Görtz) or ‘interconnections’ (Alexandra Dumitrescu) or ‘braiding’ (Greg Dember) might work just as well or better. That is the kind of nuanced enquiry the field of cultural metamodernism explores, usually with examples from contemporary culture, and I wish this community of scholars well.[24] Those working in the field advise me that there are metamodern elements in many of the popular culture shows I have recently enjoyed. Stranger Things and Cobra Kai on Netflix, for instance, share the postmodern feature of ironic self-reference and yet clearly transcend that with a sincere depth of enquiry into the interior states and learning journeys of the protagonists; the irony is sincere and the magic is real. Moreover, it is worth considering that Time Magazine listed Phoebe Waller-Bridge as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2020 for her work on the hit television series Killing Eve and Fleabag, both of which I loved. The nature of that influence was cultural, and metamodern in spirit.[25]

I confess that I only read V&vdA’s seminal Notes on Metamodernism paper properly quite recently. I say ‘confess’ because it made me feel sheepish about having used the term ‘metamodern’ as if I knew what I was talking about, while not having digested this deep and prismatic consideration of it. This feeling of sheepishness is all the more real because there was a large community on an active website or ‘webzine’ between 2009 and 2016 that shared the enquiry that I was completely unaware of until a few months ago.[26] It feels absurd to apologise on behalf of people I am only loosely affiliated with, to a research community I have barely met, but in a sense I am sorry. There is a significant body of diligent and heartfelt scholarship on the idea of metamodernism that has mostly been ignored by those who encountered metamodernism, as I did, via Hanzi Freinacht, and while we can make some sense of how that came about (and I do below) it still feels, at the very least, impolite.

Since Notes on Metamodernism was published in 2010, Google Scholar mentions of ‘metamodernism’ moved from single digits in that year steadily into the hundreds, and the number is now over 400, with over 2,000 in total, overwhelming in reference to Vermeulen and van den Akker and other scholars considering metamodernism in similar ways. V&vdA also published an updated reflection on responses to their paper in 2015, which is recommended reading.[27] The V&vdA perspective on metamodernism generated a whole community of enquiry, and the Arts and Humanities Research Network in the UK has supported related work on metamodernism since 2018.[28] Moreover, much of the scholarly leadership comes from women. In her PhD (2014) and subsequent publications Alexandra Balm (née Dumitrescu) offers a spiritual emphasis within a broader societal vision, including a close examination of Arundhati Roy’s Booker Prize-winning novel, The God of Small Things. It is important to note in passing that Balm (then Dumitrescu) appears to have theorised metamodernism as a category in literature before Vermeulen and van den Akker, and she offers a related but distinctive emphasis, locating the metamodern patterns of integration between masculine and feminine, rational and emotional and in ‘recuperating traditions’.[29] In a similar, but again distinct vein of enquiry, Linda Ceriello links the metamodern sensibility to forms of mysticism grounded in secular spirituality, illustrated, for instance, in Russell Brand’s rhapsodic flirtations with transcendence.[30] Alison Gibbons emphasises ‘the resurgence of historicity’ in the context of reckoning with the Anthropocene after the perpetual present of postmodernism.[31] My overall impression is that metamodernism is no passing fad. The term is here to stay.

A successful kidnap?

There is an open question now about the legitimacy of the term’s scope and remit outside of academia, however, especially because many people who invoke metamodernism to make sense of their work are para-academic or post-academic, often writing as intellectual journalists or policy researchers and often having advanced degrees, but mostly having little inclination to confine themselves to scholarly captivity or write for academic journals. It just somehow doesn’t feel metamodern to play the academic game. In so far as this observation is accurate, it may say something about the epistemic and scholarly style of metamodernism, which acts as a tacit and sometimes explicit critique on conventional academic knowledge production.

For instance, I came across metamodernism through Hanzi Freinacht’s first book The Listening Society, in which the primary author is an academically trained sociologist who happened to undertake what sounds like a life-changing apprenticeship in Michael Common’s theory of cognitive development called The Model of Hierarchical Complexity (MHC), and his political vision is informed by cross-disciplinary understanding. Hanzi’s first book is insightful and referenced but it is written in an essayistic style and it is mostly a vision of a deliberately developmental society rather than anything self-evidently metamodern in the prior meanings of the term, in culture theory at least. In the appendices of that book, which is the literary equivalent of behind the bike shed in the playground, Hanzi even describes their adoption of the term metamodern as an act of ‘idealistic piracy’ and claims they are ‘shanghaiing’ (kidnapping) it for the greater good.

With all due respect to the victims, it was a successful kidnap. Indeed, Hanzi’s books are now synonymous with metamodernism for many. On reflection, however, The Listening Society’s main contribution to metamodern thinking is less about original intellectual substance or even innovative rhetorical style (though it has both) and more about the fact that it enriched existing metamodern theorising with integral meta-theory and thereby deepened its significance and broadened its applicability.

James Hillman’s Puer/Senex distinction is useful here. Puer embodies a kind of creatively destructive and self-confident energy with a wide-ranging spirit of eager fantasy, while Senex is the established and orderly understanding or wisdom; and there is naturally tension and competition between them. Hanzi is very much writing in the spirit of Puer rather than Senex, but it seems implicit, and has to some extent been conceded explicitly, that the spirit of the Senex role in the book is not so much academically established metamodernism, but the progenitor of Integral Theory, Ken Wilber. To put it straightforwardly, the subtext of Hanzi’s books is that he is saying: Integral Theory has failed, and metamodernism is now called for. In that quest, Hanzi attempts to use the sensibility of cultural metamodernism that he has kidnapped to usurp Integral Theory and subsume it within political metamodernism.[32]

For those familiar with Wilber’s work, even his most basic conceptual map of the four quadrants of reality, a meta-theory stripped to its barest essentials helps us to understand the evolution of metamodernism.[33] Those familiar with integral thinking use this meta-theoretical tool to locate the provenance and application of phenomena, and to make sense of existing theorising. From that perspective alone, V&vdA metamodernism looks ‘true but partial’ (an integral term of art) for two main reasons: it’s primarily a left quadrant’s endeavour (I and We, psychology and culture) and it is implicitly but not explicitly developmental in outlook. By implicitly developmental I mean that the metamodern sensibility does not entail the normative vision of a deliberately developmental society at all, but it does co-arise in response to a new cultural curriculum, as developmental theory would expect. For instance in Robert Kegan’s constructive developmental terms, the neo-romantic, post-tragic and planetary aspects of the cultural sensibility of metamodernism is ‘the hidden curriculum’ of metamodernity and corresponds to what he calls ‘constructive postmodernism’, something we learn to grow into through the coalescence of cultural evolution and personal maturity.[34]

To Hanzi’s relatively young and integrally informed mind, unfamiliar at that stage with Borgmann or Gonzalez or others, Notes on Metamodernism (and its subsequent elaborations) is therefore crying out for expression in the other quadrants, for a developmental appraisal of how the metamodern sensibility comes into being, and for a blueprint of what might follow normatively for individuals and cultures. And here is perhaps the key point. That impulse to combine cultural metamodernism and Integral Theory is not just intellectual but intensely and self-consciously political.

Integral Theory is not particularly political and in some ways can even be seen as anti-political; it is famed for its balance and perspective on competing points of view. The politically metamodern impulse, on the other hand, arises because today we are living with a world that feels like it’s unravelling through climate change, culture war, bio-precarity, political corruption and myriad economic failures. In that context Integral Theory has to evolve to something post-integral if only because it feels like the bottom right quadrant (the systems and structures of society) is on fire; the conflagration is already figuratively spreading to the other quadrants on the map, and literally in the sense of houses, cities and even countries burning to the ground. Any model or outlook that ignores the need for a new politics, including cultural metamodernism, therefore risks looking obtuse. Enter Hanzi Freinacht, who speaks with an integral understanding and with an apparently intuitive metamodern sensibility but to that prevailing common-sense understanding that ‘something must be done’.

There are some chicken-and-egg dynamics here. On the one hand, metamodernism comes after Integral Theory and tries to supersede it, but it is only because of the historical conditions of metamodernity – culture saturated with decades of intellectual and cultural (post)modernism – that meta-theory as such becomes possible, as well as necessary. In this sense, metamodernity gave birth to Integral Theory, not the other way round. The conditions of metamodernity and its historical antecedents provide the raw materials and impetus for Integral Theory, alongside other meta-theoretical frameworks that contend with the relationship between the spiritual and material features of life including, for instance, Iain McGilchrist’s neurocultural analysis and Roy Bhaskar’s critical realism.[35]

In that fuller meta-theoretical and historical context, Hanzi deserves to be widely read and admired, regardless of inevitable critiques of his work; for instance Sarah Stein Lubrano amusingly quipped that political metamodernism is just ‘Hegel for hippies’ and Minna Salami notes in her chapter for Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds that Hanzi’s ideas often look suspiciously like feminism in disguise. However, we can all admire any attempt to use the intellect in good faith to try to forge a pathway to a viable and desirable future. My pragmatic inclination is therefore to hope that there is scope for a fertile dialogue between different kinds of metamodernism and that, as Daniel Görtz elegantly put it on the Metamoderna mailing list: ‘There is plenty of champagne to go round.’ [36]

Conundrums of metamodern normativity

Perhaps there is a figurative champagne reception to be had, but would the people present be celebrating the same thing? There are significant divergences between these two major streams of metamodern endeavour. For instance Hanzi speaks of ‘dividuals’ rather than individuals, to reflect the extent of our historical and biological inheritance and networked interdependence and our reciprocal malleability, while cultural metamodernism would be more inclined to protect our uniquely individual interior experiences from that kind of systemising abstraction. Moreover, cultural metamodernism tends to locate the active ingredient of metamodernism in the relationship between the cultural artefacts and the interiority of people, rather than in the people as such; for some, metamodernism is a phenomenon, not a field, and certainly not a programmatic agenda that seeks to bring about a different world.

I have mixed feelings here(!) I am inclined to say that political and cultural metamodernisms are both completely distinct endeavours and part of the same pattern of meaning. As an ‘intuition pump’ way of resolving this tension, I wonder – since Jean-François Lyotard summarised the postmodern attitude as ‘incredulity towards metanarratives’ – what the metamodern attitude might be incredulous towards. There are many possible answers here, including incredulity towards technological solutionism, which is better characterised as hypermodern. I notice, however, that my personal answer appears to involve tacitly ‘picking a side’ in metamodernism’s internecine cold war. In so far as I am metamodern or understand metamodernism, my incredulity is towards neutrality, by which I mean disavowal of our role in the direction of everything that is underway. By implication, I mean incredulity towards those aspects of cultural metamodernism that insist they are not normative in nature.

I think Hanzi should have been more generous and transparent about his kidnapping-is-the-new-adopting use of the term metamodern, but when he says he did it for the greater good, I feel he is in good faith. There is a curious streak of something like purist humility in van den Akker and Vermeulen’s cultural metamodernism that resembles the contested logic of the old-fashioned is/ought distinction in ethics, which, roughly, contends that you cannot derive normative implications from statements of how things are. In their 2015 ‘Corrections and Clarifications’ piece especially, V&vdA are keen to delineate their descriptive take on metamodernism from anything more prescriptive. That is their prerogative, but I am just not sure that descriptive/prescriptive distinction holds, especially when what is being described often stems from a background sense that the world as we have known it is collapsing, which means that something is tacitly prescribed in the process too, not necessarily in Hanzian terms, but in the feeling that something must be done.

And yet I suppose there is some hubris there too, because humans are never as in control as we think we are. Covid has taught us that, and much else besides. Moreover, normativity is vexing in all sorts of ways. For instance as I became familiar with postmodernism, I began to feel some generosity of spirit towards it, which obliged me to work harder to identify what exactly metamodernism could add at a normative level – the first of many conundrums of metamodern normativity. A lazy summation of postmodernism is that it is about style rather the substance, that it lacks depth and soul, easily collapses into mad relativism and gets lost in critique, self-reference and endless perspective-taking; on this view of it, postmodernism lacks generativity and cannot help us to save ourselves from ourselves. None of that is strictly false, but it is straw-man-like, and there are other ways to see it. For instance, Derrida appears to contend that there is nothing outside the text or no context that is outside-text (il n’y a pas de hors texte),[37] but what he really means is that there is nothing outside of hermeneutic context, and it follows that it’s incumbent on us to understand the context in which meaning arises; that sounds like an invitation to back up all the way to our collective imaginary – a key metamodern focus for some that is perhaps quintessentially postmodern. And Lyotard does not say there can be no metanarratives of big stories, just that we are right to be sceptical about them (and surely that’s sound advice?). Moreover, he suggests knowledge has a narrative character and that our responsibility is to own up to the implicit ethics and metaphysics in the stories we live by (the problem with modernism is that it disavowed those commitments), which sounds a lot like the metamodern lingo of ‘co-creating a more conscious society’. And the putatively metamodern emphasis on serious irony would not be new to the apparently arch postmodernist Richard Rorty, and nor is solidarity with all beings and all perspectives; consider the title of his classic text: Irony, Contingency and Solidarity. Moreover, it’s not true of postmodernists that ‘they have no positive ideas’; for starters, philosophical pragmatism can be seen as postmodern and the putatively metamodern reappraisal of Bildung looks quite a lot like Rorty’s pragmatic case for sentimental education.[38] And in today’s context of data extraction, behavioural manipulation and smartphone addiction, who better than Michel Foucault to remind us of the link between knowledge and power, the surveillance (panopticon-like) apparatus of the disciplinary society and our scope for emancipation? My impression is that in the battle for the perception of context and the creation of tools to remake the world, postmodernism is better armed and more versatile than we tend to think.

I share this short appraisal of postmodernism to contextualise a second conundrum of metamodern normativity about Hanzi in particular. However well developed the vision of a deliberately developmental society may otherwise be, it is unclear whether Hanzi really shifts the dial of our experience and perception beyond (post)modernism. Hanzi’s iconoclastic writing style is designed to bamboozle and thereby circumvent postmodern cultural reactivity. I believe he does achieve forms of metamodern oscillation in his readers between, for instance, hope and despair, and sincerity and irony, and he does help move us beyond postmodern ‘whataboutery’ to something that feels closer to the whole truth of our experience and scope for normative directionality within it. Yet the idea of a listening society (and the ecosystem of political institutions and practices designed to facilitate it outlined in Nordic Ideology) can be seen as more like a hybrid than a synthesis: two distinct things characterised as being one thing that is two things, rather than a third thing that emerges from the relationship between the two.

In a morphological sense, the Hanzi vision is inherently multi-perspectival in nature (‘Solidarity with all beings means solidarity with all perspectives’) which can be seen as primarily postmodern in spirit. And the underlying vision of a self-consciously therapeutic and deliberately developmental society is arguably modernist in its system-building, universalising and emancipatory spirit. In the comment thread to an online essay mostly targeting Hanzi that was later republished by Perspectiva, Samuel Ludford puts the challenge like this: ‘Postmodern discursive norms and modernist politics does not amount to a developmental synthesis at either level. What it amounts to is the cultural logic of late capitalism writing itself an alibi.’[39] On reflection, this line might not be as clever as it sounds, but it brought to mind the idea of surveillance capitalism, which is defined with analytical precision by Shoshana Zuboff, but can perhaps be seen more loosely as a totalising modernist infrastructure that monetises postmodern cultural tropes of hyperreality and identitarian polarisation.[40] Surveillance capitalism is clearly part of the context of metamodernity, and it influences our structure of feeling, but there is no oscillation to speak of, nor any enchanting emergent properties up for grabs. I think this means that metamodernism has to reckon more clearly with its defining structural and cultural limitations in metamodernity. Since that context is both modern and postmodern but without necessarily having any higher-order synthesis or funky oscillation beyond our own projection, metamodernism struggles to create distinctive normative vision without losing its conceptual fidelity to metamodern context and sensibility. To be fair, and to temper my incredulity towards them, this subtle point may already have been intuited by Vermeulen and van den Akker.[41]

The third and directly related conundrum of metamodern normativity is that it is not straightforward for metamodernism to be political as such. Although there is a sub-culture of ‘The New Left’ that links metamodernism to progressive policy programmes, and Hanzi’s think tank, Metamoderna flirted with calling itself The Alt-Left to offer an alternative to the Alt-Right, there have been many right-wing appropriations of the term metamodernism. For instance, Greg Dember writes of the Alt-Right as follows:

… While their behaviour is frequently vile and degrading towards others, from their own vantage, they are engaging in ironic play disrupting a hegemonic culture that leaves no room for their inner world. ‘Metamodern’ helps describe the cultural-behavioral reaction observed here. A descriptive, epistemic theorization of metamodernism allows for exemplars not favoured by the theorist. Put plainly, if ‘metamodernism’ is used to refer only to content you agree with and like, it’s probably not metamodernism.[42]

Whatever one’s relationship to metamodernism, saying it is fundamentally left-wing or right-wing or centrist is not going to work, or help. In a world shaped by the private co-option of the public realm, myriad addictions, ecological collapse, governance failure, reassertions of identity and pleas for survival, the old-fashioned binaries of individual/collective, freedom/equality, state/market and tradition/change are otiose. There is scope for conceptual renewal here grounded in a new aesthetic, and that feels like a metamodern enterprise to be encouraged.

I am not saying that metamodernism should be post-political in the sense of equating politics with technocracy. On the contrary, I feel metamodernism has to be more astutely and deeply political in its offering (both to meet the needs of the time and to be true to itself). Metamodernism can influence events by being in some way quasi-political, for instance influencing politics through cultural or educational innovation, or pre-political, through the cultivation of relational and civic virtues. Most fundamentally, metamodernism can be meta-political in the sense that the structure of feeling that defines our time may contain clues to what politics as a whole should be about; that is arguably what The Alternative political platforms in, for instance, Denmark and the UK are about. However, any successful meta-political venture, for instance Bildung at scale as the organising principle of society, needs a strategy for outcompeting other meta-political movements, for example, QAnon or Neoliberalism, and such a strategy may have to be concerned directly with how to attract and wield power, and therefore be more conventionally political in nature. None of this is easy. [43]

The third refrain on metamodern normativity is actually a celebration, because the view of metamodernism as a path-forging and future-creating endeavour is by no means exclusive to Hanzi, and there are already quasi-political, pre-political and meta-political ventures under way. For instance, in addition to those mentioned above, Tomas Björkman invokes metamodernism as the cultural inheritance that behoves us to consciously fashion a more viable and desirable collective imaginary.[44] In a similar spirit, Lene Rachel Andersen uses the term to describe the construction of a new cultural code that works for our times, transcending and including prior cultural codes, including the indigenous, the premodern, the modern and the postmodern. Both Björkman and Andersen lay out normative pathways, often relating to the praxis of transformative civic education called Bildung.[45]

Metamodernism is also used as an umbrella term to describe the overarching pattern of enquiry and endeavour that connects the work of The Alternative political parties in Denmark and the UK, who seek ‘a new politics’, Daniel Schmachtenberger’s Epistemic NGO – Consilience, the spirit of ontological design in the Game B community, and a range of theorists and practitioners working on regeneration, such as Joe Brewer on bioregionalism, perception-generating methodologies like Nora Bateson’s warm data labs, Jason Snyder walking the talk of ‘cosmo-localism’ and Michel Bauwens’ advocacy of peer-to-peer practices. Also sharing this inclination to connect inner and outer change, we could mention Giles Hutchins and Laura Storm on Regenerative Leadership, Gregg Henriques’ Theory of Knowledge community and Daniel Christian Wahl on Designing Regenerative Cultures. We might also include Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer in their work on Leading from the Emerging Future, Elizabeth Debold and Thomas Steininger’s work on Emergent Dialogue, and Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations.[46]

These theorists and practitioners do not necessarily call themselves metamodern, but they are operating in ‘a time between worlds’ and are responding to the metamodern structure of feeling. And yet there’s a twist, because as this discussion moves towards a close, I notice an elision and conflation (not oscillation!) between two kinds of betweenness in metamodernism discourse – the time between worlds and the relationship between modernism and postmodernism. Clearly, these are ontologically and historiographically distinct phenomena, and that begs the question of just how much work the meta in metamodernism is doing.

Meta as a triple agent

It has taken me five years to make friends with metamodernism. For too long I had been looking at the meta in the ‘metamodern’ without really seeing her, without grasping that she, Meta, is a kind of triple agent, hiding inside the concept as a protean spy, and using the modern as an elaborate cover story. The meaning of metamodernism is notoriously elusive, but it becomes enchanting when we notice that it varies depending on which features of herself the beguiling host discloses at any given moment; the cultural between, the political after or the mystic beyond. [47]

As indicated, we learn from literary scholars and cultural theorists that metamodernism is discerned in cultural artefacts with qualities of signification that are in some sense oscillating in between (metaxy) the apparent progress and optimism of modernism and the critical and subaltern perspective of postmodernism. Yet the initiatives and practices that are derived from that sensibility can only arise after postmodernism. If that paradox of the after being a kind of in between what went before isn’t confusing enough, many who identify with metamodernism at its most broadly conceived seek, somehow, to move beyond all forms of the modern, including the metamodern. It’s exhausting being a triple agent. Meta wants to break free.[48]

If you’ll permit the indulgent metaphor, one way to see this improbable analytical love story is that the main protagonists’ ‘after’ and ‘betweenness’ enjoy conceptual coitus and create a higher-order betweenness that is not merely in between the modern and postmodern but open to the possibility of a different kind of after that is truly new, the out-between that is implicit in ‘a time between worlds’ where we metamoderns seek to move beyond the old relationship in between ‘Mo’ and ‘Pomo’. We move out of that betweenness to being between the metamodern moment and whatever is beyond the modern, which has been envisaged by many great sages and prophets like The Mother and Sri Aurobindo, or Jean Gebser, but it remains, for now, inherently mysterious.[49]

The fact that the meta inside metamodern itself points towards at least three ontologically distinct phenomena (between, after and beyond) gives metamodernism valuable heuristic vitality and agility. Indeed, in his chapter for Dispatches in a Time Between Worlds, on Metamodern Sociology, Hanzi Freinacht recasts metamodernism with reference to Sean Esbjörn-Hargen’s (2010) idea of a ‘multiple ontological object’. Hanzi goes on to distinguish between six uses of metamodernism, but these are arguably different functionalities, not different ontologies, and the question of what metamodernism qua metamodernism is remains moot. It helps to show the different work ‘meta’ is doing in each case.

When metamodernism is a cultural phase with a corresponding ‘sensibility’ (e.g. Vermeulen and van den Akker), meta is after and between.

When metamodernism is a developmental stage of society and its institutions (e.g. Lene Rachel Andersen), meta is mostly after.

When it’s a meta-meme (e.g. in the study of history), meta is after and between.

When it’s a relatively late and rare stage of personal development (e.g. Hanzi Freinacht), meta is after.

But when metamodernism is used to speak for a new paradigm with its own philosophy with accompanying theologies, and when it’s used to mean a movement or project, meta is used partly as after, but also as beyond.

To look at this another way, what comes after modernism and postmodernism is that we are not subject to them in the way we used to be. Like some kind of Escher drawing, we are after them only when we see they are still with us. The point is that we can relate to them better as objects of enquiry as well as sometimes being subject to their patterns of continuing influence in our experience. And yet surely that kind of betweenness, that after, is not the end of the road? Hanzi says there is no cultural code beyond the metamodern. More generally, metamodernism is sometimes presented as a kind of Hotel California, where you can check out, but never leave.

That’s not my metamodernism. I risk caricaturing the views of others here, but I do so to get to the underlying tension between ‘the after’ and ‘the beyond’ that I think is a critical feature of the next wave of metamodernism. If the limitation of cultural metamodernism is its political ambivalence, the limitation of political metamodernism is its ambivalence towards metaphysics.

Metamodern metaphysics

Zachary Stein targets this issue directly in his extraordinary Integral Review paper, ‘The Metamodern Return to a Metaphysics of Eros’ (2018) where he draws on Charles Sanders Peirce to make the case for the need for metaphysics in general.[50] Stein argues that the way we answer ‘What is the human?’ is now critical, given that the emerging power of new technologies now renders the human malleable in unprecedented ways. The paper develops Marc Gafni and Kristina Kincaid’s work to advance a particular metaphysical view called ‘cosmo-erotic humanism’, which is grounded in a deep appreciation for the evolutionary process of love and contains a central place for ‘the structure of feeling’ as a unit of analysis, suggesting it is a generative feature of collective human life. In his conclusion Stein signals the scale of the ambition:

There is no longer any prospect for premodern forms of metaphysics after Kant, Darwin and planetary-scale computation. Yet the modern and postmodern absence of metaphysics has created its own problems by leaving a vacuum where answers to the most important questions used to be found. The metamodern return to metaphysics seeks to fill this vacuum of meaning by providing a new context for human self-understanding – a new Universe Story that includes a new story of self and community.

The case for the return to metaphysics is also indicated by Bonnitta Roy, who has argued that metaphysics matters because we need ‘a new mind’ and metaphysics is required to help us foster new architectures of thought, an idea further developed in her chapter for Dispatches where she writes:

The new architecture would cut out the epistemic complexity and more perfectly cohere with the rich elegant complexity of the real. By adopting a process understanding of reality, metaphysics could become a suitable guide for a Metamodern praxis, one which integrated perception and participation with the free play of imagination and memory. [51]

A feature of the new metaphysics is that it will have to integrate the immanent and the transcendent. Many of the more promising initiatives for societal renewal have distinctly premodern or indigenous features relating to returning to the land, the soil, the seasons. And although not explicitly metaphysical as such, recent scholarship by Jeremy Johnson on Jean Gebser’s aperspectival consciousness and by Mark Vernon on Owen Barfield’s ‘participatory knowing’ is consonant with ‘the evolutionary process of love’.

The point of metamodernism for me is therefore that it takes root in the best kind of soil, the new mixed in with the old, and that it has the potential to give rise to new life. The emergent properties that are evoked by the concept for me are not merely about the maturation of the relationship between modernism and postmodernism. What is exciting for me is our relationship to that relationship, because that relationship is potentially fecund, world-creating and metaphysical in character. The meta in metamodern that is most worth caring about is not passive and descriptive but generative of the kinds of creative energy we need for what Layman Pascal calls a new renaissance. That renaissance will grow in metamodern soil, so the final turn in the argument is to clarify the nature of its main nutrients.

Metamodern touchstones: interiority, intimacy, ecology, historicity

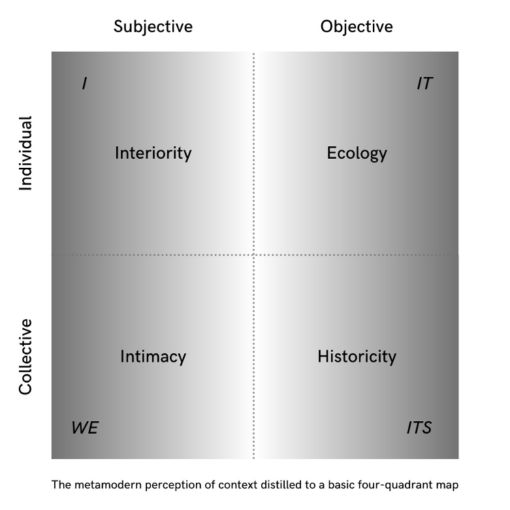

You’ve been very patient, dear reader, but please allow me to share just one more simple conceptual frame before I put my case my rest. To again borrow the simplest version of the simplest meta-tool at hand, we can map the sources of the emerging metamodern perception of context onto a four-quadrant map, derived from the most basic expression of Integral Theory, which in this context also acts as a helpful creative constraint. There are philosophical risks in any distillation, but I do this in the pragmatic spirit of ‘thus far and no further’ which I think is a valid use of this integral heuristic.[52] In doing so, I had the following criteria in mind: the touchstone terms can be seen as meaningfully post-postmodern, they have descriptive validity in our cultural context and under-developed normative potential, they are clearly cross-pollinating but ontologically distinct from each other, there is validity in their quadrant placement, and they all contain aspects of meta that offer scope to speak to the cultural between, the political after and the mystic beyond. That’s my self-imposed test to probe the scope for metamodern touchstones, and here is my answer, which by this stage in the essay, I can only sketch.

Figure 1.1 The metamodern perception of context distilled to a basic four-quadrant map

In the top left, metamodernism affirms our interiority as being non-reducible despite being as plural as it is singular and as relationally embedded as it is existentially unique. As Greg Dember puts it, informed by Raoul Eshelman:

The movements of metamodernism, classically characterised by oscillation, are driven by ‘a need to safeguard the individual’s interior experience against postmodern ironic relativism, modernist reductionism, and also from the ontological inertia of premodern tradition’.[53]

In the bottom left, typically conceived of as ‘culture’, there is a new form of intimacy arising from our sense of coexistence, what Sam Mickey calls ‘the unbearable intimacy of ecological catastrophe’ and in particular our inability to exit from the kinds of relationships that are defined by our metamodern plight, including the relationship to, for instance, mass extinction. This intimacy in the face of planetary peril is contrasted with the representation, construction and distancing irony of postmodernism, and indeed with the postmodern abuse of ‘the meta move’ as a way of subverting intimacy in general. [54]

The metamodern sensibility also seeks a deeper appreciation of how past, present and future fold together along many entangled pathways, so in the bottom right, there is a revived sense of historicity, which might also be rendered as simply ‘history’ or more subtly as ‘temporics’. This sense of historicity manifests both in the public appetite for ‘Big History’ books like Harari’s Sapiens[55] and ‘meta-history’ in Hanzi’s forthcoming work, but also in what Alison Gibbons observes as a new temporal logic driven by the need to ‘reopen the possibilities of the future’ in the context of global warming and other mass-scale crises.

The historical thinking required to understand climate change, in turn, necessitates narrative thinking; and precisely because anthropocentric narratives call for collective imagination, they are mythic structures or, in other words, grand narratives. Grand narratives of the Anthropocene fundamentally require future thinking and, resultantly, they have the potential to engender change, or at least some form of environmental intervention.[56]

In the upper right, there is a reorientation towards Gaia, not so much in terms of Lovelock’s hypothesis but in terms of a new appreciation and a new philosophical seriousness towards the objective features of Planet Earth. There has been a reckoning with our bio-precarity through the pandemic, an epic encounter between human biology and planetary geology in the Anthropocene, and an increasingly popular object-oriented ontology that entails an acceptance of processes of reality that are indifferent to human desire. We could call this ‘living systems’ or even ‘Gaia’ but I prefer ecology. I realise this term slightly subverts the spirt of the upper right as Wilber conceived of it (extant material bodies from microcosm to macrocosm) but it serves to remind us that the objective exterior material features of reality are processes and relationships. Another way to see this is in terms of World One of Karl Popper’s Three Worlds Hypothesis whereby the world of physical objects and events have their own pre-epistemic ontology; they can be understood ecologically, and, from a metamodern perspective perhaps even should be.[57] I agree with William Ophuls that ‘ecology’ has to become our master discipline, not merely a field of practice but an ontological presupposition:

Ecology contains an intrinsic wisdom and an implied ethic that, by transforming man from an enemy into a partner of nature, will make it possible to preserve the best of civilisation’s achievements for many generations to come and also to attain a higher quality of civilised lie. Both the wisdom and the ethic follow from the ecological facts of life: natural limits, balance, and interrelationship necessarily entail human humility, moderation, and connection.[58]

I accept that the validity of the simple quadrant map is creaking under the ambiguity of those four metamodern touchstones, but it is my initial attempt to distil the perception of context that metamodernists, broadly conceived, share. These are just four words, but together they contain a distinctive perception of context, and they are juxtaposed with the modern and postmodern perceptions of context that we are outgrowing.

Interiority is about reasserting the depth of consciousness against modernism’s reductionism and postmodernism’s flirtation with superficiality. Intimacy highlights forms of relational beauty and is contrasted with modernist universalism and postmodern distancing. The reopening of time through historicity is contrasted with modernist grand narratives but also with postmodernism’s perpetual present. And ecology affirms the need to reorient ourselves to the relational and process nature of material reality, while being contrasted with the environmental blindness of modernism and the miasma of hyperreality in postmodernism.

At home in a world that might not be falling apart

When seen in this light, whereby meta is a sincerely ironic ‘trinity’ of between, after and beyond, and metamodernism has four orienting touchstones of interiority, intimacy, historicity and ecology, what is on offer is a lodestar that helps to orient our perception of context. The metamodern orientation towards meaning in that context is more soulful than propositional because it involves juxtaposing and reanimating concepts that have their own ambiguities, and it therefore relies on the dignity of paradox in which several things that are not mutually consistent appear to be true at once. Indeed, physicist Niels Bohr anticipated the metamodern sensibility when he wrote: ‘How wonderful that we have met with a paradox, now we have some hope of making progress’.[59]

Metamodernism, then, is not so much a word for a new historical epoch, but rather a new disposition towards the experience of history unfolding. It is not merely an idea but an invitation to an imaginary that seasons our taste for ideas. It is not only an epistemology that studies understanding but also an Episteme that emphasises a certain kind of aesthetic understanding. And it is not a metanarrative as such, but an outlook that restores the dignity of the metanarrative impulse without being subject to it. And it’s not merely one feeling, but a whole structure of feeling; and that structure of feeling matters because it is prior to the structures of thought and society, and the domains of the political and epistemological.

In light of this sweeping scope and elastic structure, the test of the value of metamodernism is no less than this: whether it helps us feel at home in a world that might not be falling apart.

Jonathan Rowson is a writer, philosopher and chess Grandmaster who was British Chess Champion from 2004-2006. He holds degrees from Oxford, Bristol, and Harvard, was the former director of the Social Brain Center at the RSA, and an Open Society Fellow. He is co-founder and director of Perspectiva, a research institute that examines the relationships between complex global challenges and the inner lives of human beings. His latest book is The Moves that Matter: A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life. Find out more here.

You can follow Perspectiva on Twitter & subscribe to our YouTube channel.

Subscribe to our newsletter via the form below to receive updates on publications, events, new videos, and more…

Perspectiva is registered in England and Wales as: Perspectives on Systems, Souls and Society (1170492). Our charitable aims are: ‘To advance the education of the public in general, particularly amongst thought leaders in the public realm on the subject of the relationships between complex global challenges and the inner lives of human beings, and how these relationships play out in society; and to promote research, activities and discourse for the public benefit in these subjects and to publish useful results’. Aside from modest income from books and events, all our income comes from donations from philanthropic trusts and foundations and further donations are therefore welcome. Please consider donating via the button below, or via Patreon.

Endnotes

[1] This essay is a lightly edited and slightly reduced version of the Preface to Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and emergence in metamodernity, published by Perspectiva Press in June 2021. I am grateful to the following people for feedback on drafts of this essay: Zachary Stein, Anna Katharina Shaffner, Bonnitta Roy, Layman Pascal, Tomas Björkman, Ian Christie, Daniel Görtz, Jeremy Gilbert, Minna Salami and Ivo Mensch. A special thank you to Greg Dember for a range of perspectives I would otherwise not have known, and for helping me to silently ‘think out loud’ on Twitter direct message exchanges as I attempted to find connections between different forms of metamodernism.

[2] The Feeling of What Happens by Antonio Damasio (Vintage, 2000) is a classic text in this domain. In recent years, popular books that highlight the centrality of feeling to human consciousness, culture and politics include The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt (Penguin, 2013), The Age of Anger by Pankaj Mishra (Allen Lane, 2017), Political Emotions by Martha Nussbaum (Harvard University Press, 2013) and Nervous States by William Davies (Jonathan Cape, 2018).

[3] Some benign confusion and gentle weariness over terminology in this terrain is a feature, not a bug. In fact, it’s a sign that we are paying attention. I am reminded of Bonnitta Roy’s paraphrasing of Dogen, the 13th-century Japanese philosopher poet: ‘If you make the difference, you suffer the sameness. If you make the sameness, you suffer the difference’.

[4] At first blush, that may not look new, because postmodernity is already characterised as a time that is reflexive about modernity, albeit usually from a critical distance, and with ironic detachment, rather than from a spirit of existential tenderness, openness or vulnerability. To help clarify the difference, consider Umberto Eco’s reflection in the postscript of his novel The Name of the Rose: ‘I think of the postmodern attitude as that of a man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows that he cannot say to her “I love you madly”, because he knows that she knows (and that she knows he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland. Still there is a solution. He can say “As Barbara Cartland would put it, I love you madly”.’ Eco goes on to say that since the man has avoided false innocence, he will nevertheless say what he wanted to say to the woman: ‘That he loves her in an age of lost innocence.’ This perspective is reflexive about modernity and postmodernity and in that sense post-postmodern and perhaps proto-metamodern, but I think a metamodern approach would be simply to say ‘I love you’ with all the rest taken as a shared given as part of the intimacy being conveyed, or perhaps to do something more profoundly neo-romantic like reading aloud from a Barbara Cartland book for amusement value before expressing similar thoughts in one’s own words.

[5] Ten Things to Do in a Conceptual Emergency, Triarchy Press, 2009.

[6] The nature of the relationship between perception and conception is well-worn terrain in analytic philosophy that could easily swallow me whole, but it helps to keep it in the frame when we find ourselves wondering ‘why should I bother with a word like metamodern?’ For species-specific reasons relating to our survival, for social and emotional needs, and as a basis for action, we seek to perceive the world and our place in it more clearly, and we use concepts of various kinds to do so. When those concepts cease to help us perceive what’s going on, we reach for new ones. These new concepts often become available to us through some kind of historical upwelling or cultural osmosis, and they appear as new affordances that guide action in the context of a conceptual emergency.

[7] Being Ecological by Timothy Morton, Pelican, 2018.

[8] In addition to various primary textual sources, on the nature of modernism and postmodernism, I can recommend A Terrible Beauty: The People and Ideas that Shaped the Modern Mind by Peterson Watson, Phoenix Press, 2000; From Modernism to Postmodernism, edited by Lawrence Cahoone, Blackwell, 1996; The Truth about the Truth, edited by Walter Truett Andersen, A New Consciousness Reader, 1995; The Postmodern by Simon Malpas, Routledge, 2005; Who’s Afraid of the Postmodern? by James K.A. Smith, Baker, 2006; The Saturated Self by Kenneth Gergen in 1992 and The Protean Self by Robert J. Lifton in 1993 – both published by Basic Books. There is a good chapter, ‘The Modern and Post Modern Worlds’, in Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and his Emissary (Yale University Press, 2009). Ken Wilber covers this terrain in several places, but the clearest expression is probably in his book about science and religion called The Marriage of Sense and Soul (Broadway Books, 2000). I also benefited from listening to a three-hour podcast on the meaning of postmodernism by Jeremy Gilbert: Culture, Power and Politics, ‘What is (or was) Postmodernism? – 3 hour version!’, (December 2020). On metamodernism in particular, I am grateful to Brent Cooper for his heroic and compendious efforts to keep track of writing and research relating to metamodernism, which has been invaluable. You can find a range of his articles on his Medium page. I would also draw attention to his attempt to integrate aspects of metamodernism in ‘Mapping Metamodernism for Collective Intelligence’, The Side View, May 2020. Available here. I am also grateful to Greg Dember for drawing my attention to a range of sources relating to cultural metamodernism, and some of their backstories that I would not otherwise have known about.

[9] Much as I would love to have had the time to read all of Jurgen Habermas’s books, I confess that I could only read extracts and summaries relating to Discourses on Modernity (1987) and Modernity: An Unfinished Project (1996).

[10] Nietzsche, Friedrich, Twilight of the Idols, OUP (Reissue, 2008); Lyotard, Jean- François, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Manchester University Press, 1984.

[11] The lyricist who also sang this song, Pat Kane, said of these lines in a personal communication on Twitter that they were ‘Straight out of Stuart Hall … don’t forget the left postmodernism that was all about taking “the cultural turn” seriously … the whole song is about what it takes to resist interpellation (Althusser)/subjectivication (Foucault)’.

[12] Zavarzadeh, Mas’ud, ‘The Apocalyptic Fact and the Eclipse of Fiction in Recent American Prose Narratives’, Journal of American Studies, 9(1) (1975) 69–83. ISSN 0021-8758. JSTOR 27553153.

[13] Brent Cooper has provided significant service to the idea of metamodernism, and much of what follows is gleaned from his series on alternative histories of metamodernism and his bibliographic tracking of the use of the term. See for instance: Cooper, Brent, ‘Metamodernism: A Literature List: Tracking the Scattered Use of the Term’, Medium (July 2019) and ‘Missing Metamodernism: A Revisionist Account of the New Paradigm’, Medium (June 2019).

[14] For a full discussion of Borgmann and related sources, see: Cooper, Brent, ‘Borgmannian Metamodernism: Philosophy of Technology and the Bifurcation of Postmodernity’, Medium (June 2019). For Matthew Crawford on the Attentional Commons, see: Crawford, Matthew, ‘Matthew Crawford: In Defense of the Attentional Commons’, Texas Architecture (October 2016).

[15] Cooper, Brent, ‘Gonzálezean Metamodernism: Post-colonialism, Alter-globalization, and Liberation Theology’, Medium (June 2019).

[16] See for instance, Rowson, Jonathan, ‘A New Agenda on Climate Change’, The RSA (December 2013) ; Rowson, Jonathan, ‘Spiritualise: cultivating spiritual sensibility to address 21st century challenges’, The RSA (October 2021).

[17] Cooper, Brent, ‘Black Metamodernism: The Metapolitics of Economic Justice and Racial Equality’, Medium (June 2019).

[18] See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNfqr-rzj5I (06.50 mins in).

[19] Shri Nirmala Devi, Meta Modern Era, Divine Cool Breeze Books (5th edn, 2012).

[20] For a wonderful overview of spiritual life in modern China, I can heartily recommend The Souls of China by Ian Johnson (Allen Lane, 2017).

[21] Seth Abramson has written a range of articles about metamodernism for Huffington Post, on Medium, and on the website, Metamoderna.org. I have read most of this material and my impression is that he is eager to disclose the breadth and generativity of the domain of inquiry, highlight some of its main patterns, and to improve dialogue within it. However, I have been unable to discern whether Abramson has a distinctive take or angle on metamodernism that others do not.