Ivo J. Mensch

Mar 31st, 2023

‘To free ourselves, it seems like we’ll have to dismantle our inner machine – the internalised version of the imaginary of late-capitalist modernity that commodifies our attention, steers our behaviour and constrains our imagination.’

Ivo will discuss the essay with Bonnitta Roy during an online live event on April 20 at 6PM London time. They will explore the intersections between their work, with topics including intersubjectivity, social reality, and time. There will also be time for questions from the audience. Register here.

Read & download the essay as a PDF here: Solipsistic_Society_April_96ppi

The full essay is also available to read below.

Before I introduce myself, I’ll first write about solipsism and stuckness as problems that prevents us from acting decisively on our knowledge of the myriad, interlocking and compounded challenges we face. I seek to clarify, through the notions of solipsism and the social imaginary broadly, why I think we are stuck and what my life and inner work has taught me about how we might come unstuck through a kind of ontological insurgency: engaging in practices of reflexive inquiry, ontogenetic designing and applying imaginal cognition to explore the social imaginary in order to ignite its unfolding towards desired directions.

Solipsism should not be conflated with selfishness in the pejorative sense. Solipsism deals with the problem of the self being trapped in the self by the self in a kind of perpetual self-reference. This closed loop can lead to the collective belief that only individual perception, thoughts, and experience can be known to exist and therefore to be considered real. Solipsism can be grouped into two categories, one dealing with reality directly and the other with the knowledge of reality. The first is ontological and says only the self is real where the other is epistemological and says that only the self is knowable.

However subtle these distinctions are philosophically; my focus is practical: on how societal solipsism is reproduced through collective self-perpetuating beliefs and how we can approach moving beyond our predicament. A solipsistic society is therefor not a mere collection of self-centered individuals, although that is one view. Instead, it refers to collective beliefs about what is real and possible, as though everyone is wearing an epistemic straightjacket; unable to imagine how things can be known differently and changed.

In what follows I don’t want to hang too much on any single definition or variant of solipsism, but I do want to argue that when conceived in a broad sense, the condition of late modernity is solipsistic in a collective sense. The unit of analysis is the social imaginary, which can be taken as our shared psychocultural home and as forming the limits and shape of our collective awareness. It also directs our attention in fixed directions. This is a valuable concept because it speaks to the roots of fundamental problems that underlie many of our collective action problems, our immunity to change,[1] which is compounded by an atrophied faculty of the imagination.

The history of Western philosophy also has a long tradition of reality-denying, only taking what can be experienced as real, thereby forming cognitive horizons that make it harder for our imagination to go beyond. The widely quoted claim that it is ‘easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism’ captures the problem of societal solipsism and the constraints the system puts around our imagination well.[2]

We like to think we are free, but we are also kept entranced in this dream we call reality, from which we are now being rudely awakened by the really Real, which reasserts itself as the manifestations of the Metacrisis.[iii]

I propose some domains of inquiry that I believe can bring us closer to a right relationship with Reality, which is not only something concrete like nature or physical matter, but equally truths of constant flux, change and creative dynamism and outcomes of our evolutionary history we have no choice but to embody. Stuckness can only persist by denying these truths, but continuing to do so limits discovering ways forward and prevents us from moving into futures we desire or away from ones we want to avoid.

The opposite of stuckness is what I call ‘collective unfolding’. If we accept that in the West, we are in the process of losing our current, late-modern social imaginary as our stable home, as it is now appearing to liquify under the reassertion of the Real and pressures of the manifold crises, then we’ll have to learn to be in right relationship with reality’s inherent change and its patterns of unfolding and decay. We can overcome our stuckness and immunity to change by learning to creatively participate in its flows, processes, and unfoldment into new patterns of organising, which must include new forms of selfhood and knowing.

Entering and embodying unfoldment as a collective praxis can move us from our solipsistic ways to becoming a sympoietic society instead – one capable of an ongoing making of new worlds, opening up unknown spaces of possibility and realms of experience. Sympoiesis is a logic of creative making-with, systems and ecologies driving each other’s unfolding in open and adaptive ways, not afraid to outgrow familiar ways of being.[iv]

Given our predicament, this is no time to be shy. Life has taught me that there are imaginative ways of coming unstuck and to develop the trust and courage needed to enter into collective unfolding. This is what I would like to explore in this essay, and in my design for course work for Perspectiva over the next few years.

(I want to especially thank Bonnitta Roy and Hameed Ali, as this essay is infused with their minds, spirit of bold inquiry and transmission. And Jonathan Rowson and Nathan Snyder for their support, invaluable feedback and helping me focus my meandering mind.)

by Ivo J. Mensch

‘Trust the pattern.’ – Cynthia Bourgeault

‘What is most personal is most universal,’ said the psychologist Carl Rogers. It didn’t always feel that way to me, though. When I was young, I used to will myself into seeing things as if I saw them for the first time. Even though I had seen a tree many times before, I managed to stop some inner process that made things look familiar and taken for granted. I found that I could choose to be amazed, as if I was truly encountering a tree for the first time, like an alien from a desert planet who had just landed on our green earth. The interesting thing about that practice was that there was no how. I just did it. Just as I lift my arm, but can’t tell you how I do it.

I kept this practice to myself, so I don’t know how universal it is. Mostly, I expect skepticism when I say you can just stop the world from appearing the way it does. Trees were still trees, obviously, but they were also very different, more themselves and more real. Thomas Kuhn in ‘The Structure of Scientific Revolutions’ gets close to the shift of perception I try to convey: ‘though the world does not change with a change of paradigm, the scientist afterward works in a different world.’

This essay is about ways of finding that different world Kuhn speaks of, and, as an illustration, how my personal life turned out to speak to universal themes.

Finding a different world seems like a good idea. The world we have, the one I call the solipsistic society (SoSo for short) is increasingly entranced by a technological imagination and its shiny new products, but ensnared in a frantic inertia of its own making. Living in the SoSo bubble is nice and cozy for many in the developed world, but the Really Real is pulling the warm blanket called modernity off our snoozing bodies. Our society, despite featuring some real progress over the centuries, also induced a slow dulling of our grasp of causality.

Seeing the need to get out of bed before the blanket gets pulled off, and imagining better ways of being is broadly what binds the people I collaborate with – the collective of thinkers, artists, recovering academics, activists and seekers called Perspectiva. Many are self-taught mavericks who can perhaps be called post-progressive; those who no longer believe that traditional academia, politics or activism will create the change we need. Together, we try to make better sense of the relationship between our systems, souls and society. My background, steeped in spiritual practice means I mostly come from soul, but I’ve always been into systems and I even tried society.

The three are related, or more precisely – entangled. It’s a bit of a buzz word in some circles these days, but a necessary one, because we can start to think about change and our agency in more imaginative ways. Once we said: if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. Entanglement says: if you’re not part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution.

We know change is needed on a large, systems scale, but we – by which I broadly mean societies considered developed and (post)modern throughout this essay – seem unable to use the tools of adaptation and change wisely. The media, the education system, our information ecology at large, politics and much of science and technology seem to be under the spell of forces that entrain us into accepting the way things are, or rather, that we can’t imagine being different or being able to change as society and individuals. We’re taking the trees for granted and we’re only able to imagine turning them into plywood to make a profit.

The cultural critic Mark Fisher framed this particular way of thinking about the world as ‘Capitalist Realism’ in his book of the same title: ‘the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.’ […] ‘It is more like a pervasive atmosphere, conditioning not only the production of culture but also the regulation of work and education, and acting as a kind of invisible barrier constraining thought and action.’[v]

This invisible barrier and our inertia are what I am taking aim at in the hope of getting us to change direction. Because the signs of dysfunction are all too clear – species extinction, a mental health crisis, human-made global heating, societies characterised by fragmentation and political polarisation to name a few. We don’t want this, but change just seems so hard. Why?

What follows are some pointers, intuitions and insights serving as grounding for development of practices, focusing on three interrelated domains of inquiry.

The first concerns the Social Imaginary and its history, anatomy, dynamics and ontology and how it produces our particular modern subjectivity, constraining our imagination and cognition with its social structures, narratives and other sticky cultural content. The second, Temporics, concerns our experience of time, its ontology and how one mode, linear time, has come to dominate and keeps us trapped in a narrow affordance space of possibility. The third are the notions of Logos and Deep Continuity; terms originating from the world of spirituality that I want to repurpose as domains of inquiry to explore how perceived reality comes into being and what its potential and possibility are. The practice, Logoics, is also the knowledge of participating in the dynamic unfolding of reality by discovering its patterns and designing new action protocols that can produce different outcomes.[vi]

Through the praxis of embodied, reflexive inquiry and innovation in these domains we can break free of our conditioning and solipsism and enter a process of collective unfolding into imaginaries that are in right relationship with reality and supportive of the flourishing of human and nonhuman worlds alike.

First, a tale of a botched socialisation

My surname, Mensch, means ‘human’ in Dutch and German. (The Yiddish meaning is even harder to live up to.) To me, this name often seemed like a cosmic joke, since the dominant feeling of my early years, extending well into decades of adult life, was the opposite: as though I’d arrived without the human software installed, always feeling as though I’d missed the first day of school. Stranded on the wrong planet, in a body no less. I was in the world, but certainly not of it. Not yet, at least.

While being in the world, the process of becoming of it didn’t go that well. ‘Is this it?’, I remember asking myself often, while being subjected to the regimes of the school system and asked to engage in activities I could not see the point of. We just had to do the things adults told us to do. The reasons remained unclear. But if I didn’t play along, it was clear that love was generally withheld by parents and teachers alike. It was all rather puzzling, as no one gave satisfactory explanations, although clearly a lot was going on. Just the fact that anything at all was going on was pretty mind-blowing, I thought.

Adults acted with certainty in this mystery as if there was no mystery at all. They seemed to know what life was all about. I came to suspect that adults were withholding secrets about life from us kids. When it was time to go to high school around twelve years of age I was full of anticipation: finally, they were going to reveal to me what this existence thing really is about! I was ready for the truth. My naive excitement was short-lived when I encountered the curriculum and the prospect of receiving more answers that did not match my questions.

It also became clear to me that most of what passed for truth and important in life was arbitrary: made up stuff to regulate humans, get a job, procreate and perform the same thing over and over until you die. I wasn’t going to learn anything essential about existence in school I realised. I did enjoy physics and chemistry and biology, at least they seemed to deal with ‘real’ stuff. But most of that I took in from my own science books and magazines at home, often neglecting the ones from school.

I was lucky enough to discover other books that interested me in my father’s sizeable collection. A fair number were on esoteric spiritual matters and other weird disciplines, such as self-hypnosis, astral travel, mystical and religious symbolism. Experimentally-minded and super curious, I took up the challenge and tried having out-of-body experiences, gave myself headaches attempting to enforce my will on objects to effect telekinesis, to accomplish mind-reading or to acquire other extrasensory perceptions the books promised.

Noticing my esoteric interests in my mid-teens, my dad handed me three books by Carlos Castaneda, whose outrageous stories as a shaman apprentice I took as a manual for staging a prison break out of normality. It marked the start of properly venturing off the standard social script and going full DIY shaman. I began to radically question everything that was an accepted description of reality. I devised a host of practices, next to adopting a generally withdrawn and ascetic attitude to life, eventually finding inner refuge in spacious places and where my physical being was of little importance.

My practices taught me much about the power of imagination, will and perseverance and how it can alter our ways of seeing and of experiencing reality directly. This kind of imagination was not a retreat into a dream world filled with fantasy images, it was more of an agentic and directed attention that seemed to change the shape of my consciousness and perspective on reality. I used basic prompts, such as ‘why am I not that other person?’ questioning why my personal consciousness seemed tethered to my body located in a particular part of space.

Or I would focus intensely on matters you would not generally question, such as observing that two objects do not occupy the same space – why? Or looking at a moon ‘over there’, but ‘seeing’ it was really in my consciousness. Actually, the whole world, including my body, seemed to be in my consciousness – which was where exactly? Or I would simply look with fresh eyes at basic phenomena such as movement, following objects like cars and seeing them change shape in my visual field as if movement was not dependent on an object moving in space. I saw pixels change on a screen called consciousness. Subject–object distinctions readily collapsed or reversed following these experiments.

My inquiry also seriously messed up my sense of selfhood. The end result of my tinkering with consciousness, a strong turn inwards, radical curiosity, developmental distortions, compliance issues in the school system, bodily and emotional dissociation, bookishness and a wandering life as a loner was a botched socialisation. It led to a porous ego structure with plenty of escape hatches to transpersonal and other non-consensus realms of experience. Most of my time between seventeen and twenty-five was spent in different kinds of witnessing states, with my body and the ‘real world’ somewhere on the horizon of an experience of space, vast and alive and certainly more interesting than the human world.

I was able to sustain this state from the ages of twenty to twenty-five because I hardly had to participate in the complexities and demands of society. After dropping out of school and working a series of odd jobs, I eventually found myself part of a roughneck crew of greenhouse builders in the USA. For five years, we travelled from state to state, erecting steel and glass structures in a few weeks time before moving on to the next patch of virgin land in rural North America or its city suburbs. It was the simple life I craved, because my insatiable inquiring mind was entirely my own. As long as I worked hard, nobody cared about me, even though I spent 24/7 with these men, staying in cheap roadside motels. All my body had to do for about ten hours a day was cut glass, carry steel, be fairly good company and eat. In the evenings I studied spiritual books and philosophy while the others watched TV.

I eventually came down from my transcendent state. I quit life on the American road and pressures of socialisation won out because of my re-entry into more demanding social situations, like having my first ‘romantic’ relationships. The vast space I called home faded, became a memory, a mere echo of the direct experience of its infinite depth and aliveness.

There were valuable lessons learned from venturing off the prescribed human script for socialisation into consensus reality. It taught me that what we usually consider as real, such as time and space, or what we consider separate solid objects, including our bodies, aren’t exactly what we agree they are. I lived a slow-motion and conscious experience of how assimilation into the standard world view happens and how much of our perceptual potential is eventually closed off, repressed or relegated to fantasy.

No matter how interesting and pleasurable the spaciousness, grandiosity and illusions of my enlightenment were, I don’t think my DIY spiritual forays are a good example for others to follow. I did not know it at the time, but I suffered and stunted my development. Despite my sincere curiousity, having found truths and insights into the nature of reality, much of my inner adventure was driven by avoidance. Spiritual bypassing, as I later discovered it was called.

Although I had a few deep friendships (with other misfit metalheads), I had little capacity for making contact and actively avoided people for weeks. Bodily boundaries, a solid self? I remember being more like a fluid blob of consciousness that morphed and merged, rather than made connections; neurotically moving from ghostlike alienation and hyperautonomy at one end and merging and loss of my fragile selfhood at the other. I had no personal desires other than to be left alone. I felt lost, on the side-lines of a human game others knew how to play. In which success seemed to depend on an unquestioning attitude to life. ‘Join the dream’, seemed to be the unrelenting message. But I couldn’t, even if I wanted to.

One mistake after another

I was still very much in the afterglow of the experiences in my mid-twenties. After life on the American road, I exchanged glass and steel for wood, working as a carpenter on mega yachts for the super-rich. By then I had already devoured a sizeable library on Daoism, Buddhism and other wisdom traditions. Ken Wilber’s books on integral theory which I started reading during the greenhouse days, were another major influence. I was convinced I had visited the higher realms of consciousness he described. I also learnt that many of my DIY practices, to which I had given odd names, had some universality to them and were actually variations on techniques found in some of those traditions: looking at what I’m seeing; chasing prelinguistic thought forms back to their origin; the long, intense concentration on objects; mirror-gazing to effect subject–object reversals. They worked.

Determined to find my way back to these realms, I decided to learn meditation, something I hadn’t done much of. I liked the Daoists. Their sages were mavericks and wandering loners, with whom I easily identified. But since I could not find a Daoist teacher in Amsterdam, I settled, somewhat reluctantly, on Buddhism. (The first noble truth that says life is suffering did not sit well with me, as I was really good at bypassing suffering). The Tibetans gave off a Catholic vibe and seemed too fussy and colourful to an atheist Protestant. But Zen seemed sufficiently to the point, and was advertised as a direct path, which appealed to my impatient nature.

For a few years I frequented the Amsterdam Zen Center, slowly steeping in the Buddha Way, overcoming matters ranging from knee pain, to atheist aversions like bowing to a wooden Buddha and reciting sutras as if in a church. But no residential practice was available there. Since I was still intent on leaving behind the mundane world, I started to seriously entertain the idea of becoming a monk. There wasn’t much to renounce anyway. Having a career didn’t interest me one bit. Stuff I was interested in was usually academic and wide-ranging, but because I lacked diplomas I had no access to higher education. I was also periodically homeless, sleeping on friend’s couches between temporary rentals. Relationships felt like traps and a family life with kids seemed like the greatest horror of all.

Eight years after building my last greenhouse I returned to the USA to start practice at a residential Zen center in Salt Lake City, in the desert state of Utah. My Zen practice went perfectly – if perfection is like Dogen Zenji’s summation of his life of practice as ‘one continuous mistake’. Mine was still to a large degree informed by the desire to repeat my earlier experiences and to transcend myself out of this mess called ‘real life’. It didn’t work, but I had lots of fun trying. My Zen outfit, the Kanzeon sangha, was largely a wild bunch of seekers who intermingled with Ken Wilber’s budding Integral community in the neighbouring state of Colorado. The post-retreat parties were legendary and not what one would associate with Zen-like behaviour.

The head teacher, Genpo Roshi, was a spiritual innovator and not afraid to take everyone to dark places. He had to constantly navigate going off the Zen Buddhist script, risking expulsion by the traditionally minded Soto school headquartered in Japan. A tantric, crazy wisdom streak that fuelled the whole thing also brought it crashing down.[vii]

I have no regrets about how I spent those years, culminating in ordination as a monk in the Soto Zen lineage in 2009. A firm foundation of meditation was laid during many weeks spent in retreat. Many of my close friends stem from that period as nothing forms bonds as being on a spiritual adventure together. Even though, from a more conventional point of view, I stunted my worldly development for a good decade or so.

I noticed that many of my fellow Zennies were like me; state-chasers, rather than grounded ‘chop wood, carry water’ types. Many were at home in transcendent places but dysfunctional on an interpersonal level and in worldly life. By then I understood intellectually what spiritual bypassing[viii] meant and began to sense that much of my search was not about living in reality at all. I realized I was a classic case of using spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep or avoid facing unresolved emotional issues and psychological wounds.

My ordination also felt more like an ending of a process than a fresh start on the Buddha Way. By then I realised I needed a path where the grunt work on the wounds of my past and personality took primacy, without it being mere psychotherapy or analysis. I left the sudden path of Zen for the gradual one of the Diamond Approach (DA) where the difficult work of integrating and metabolising egoic material started. It is emotionally challenging, in the first years at least, as repressed material and ego structures are brought to consciousness before giving way to a sustained depth of presence and experiences of nonduality of various kinds. It is also strongly focused on the body and its mental patterning, which offers a deep insight into the unity of body and mind. The journey includes a total body-energetic work-over, which in my case was a wild, but much-needed grounding to counterbalance my mentalising transcendent tendencies; the old escape hatch, up and out to spirit.

Furthermore, and this is a significant difference with Zen where kensho, (sudden awakening), just happens (or not), you get to understand your realisation, as you progressively explore every corner of your personal history, cultural conditioning and ego-structure, how these relate to transpersonal aspects of being and the ways they inform your conduct and view of the world. The DA is also non-monastic, you’re asked to function in the messiness of worldly life, not to renounce any of it.

The Machine is Us

After being alive for almost half a century, that personal–universal connection is now clearer. My journey – from transcendent escapist solipsism, back to earth and into embodiment; from spiritual bypassing to facing up to suffering and getting real about addressing it – is one that I believe we are asked to make as a society. Spiritual bypassing is not just an individual matter, it is also something we do collectively.[ix]

As I proposed above, our society is avoiding reality by keeping our awareness fixed within a social imaginary that is no longer taking cues from the Real, but mostly from within itself. It has become a collection of memetic bubbles; a mix of comforting stories, misinformation, cognitive dissonance, bias, magical and tribal thinking, confusion, habits of mind, social conventions, constructed illusions and ideology. It recycles tons of bullshit[x] thrown at us, primarily by politicians, pr-companies and advertising. It’s not hard to imagine that this symbolic load on our minds has only increased with the advent of the internet, the appearance of the smartphone and our cultural shift online. Our lives are increasingly mediated by screens and algorithmic governance.

Have a look at the amount of data being produced and consumed worldwide. Today it is 50-fold of what it was in 2010 and is set to almost double again between 2022 and 2025. A large portion of that data is behavioral and used to train bots that send us targeted, personalised advertising to turn us into perfect consumers or the right kind of voter, if the goal is to swing an election.[xi]The social imaginary, powered by invasive technology, using insights into our behavior and a convergence with capitalism, has become a powerful teacher of desire.

Some commentators have called this total system, in which culture, technology and capitalism have merged, The Machine.[xii]This name captures it quite well if we realise that the invasive nature of the system has turned our own bodies and minds not only into machine parts, but also into its fuel and product. Our minds and imagination, and therefore our approaches to change and visions for the future are its products too. To free ourselves, it seems like we’ll have to dismantle our inner machine – the internalised version of the imaginary of late-capitalist modernity that commodifies our attention, steers our behaviour and constrains our imagination.

Why do I keep dropping the term social imaginary? Why not just say culture? Because culture is still kind of in your face, whereby the imaginary is more in the background and out of view, but it has real causal impact. It’s the difference between weather and climate, or emotion and mood. The imaginary is more temporally extended and colours our lives with a diffuse sense of meaning, helping us to make sense of and to ‘feel’ situated in our lifetime. It employs grand narratives such as ‘progress’, and allows for a host of social practices that uphold these narratives and our faith in them. Before moving on it’s helpful to ground the notion of the social imaginary, using some quotes from influential thinkers who developed the term in various ways.

The German sociologist Jurgen Habermas wrote of:

‘the massive background of an intersubjectively shared lifeworld. Lifeworld contexts that provided the backing of a massive background consensus’.[xiii]

The sociologist and philosopher Charles Taylor wrote extensively on the social imaginary, mostly from a social practice perspective:

‘Our social imaginary at any given time is complex. It incorporates a sense of the normal expectations we have of each other, the kind of common understanding that enables us to carry out the collective practices that make up our social life. This incorporates some sense of how we all fit together in carrying out the common practice. Such understanding is both factual and normative; that is, we have a sense of how things usually go, but this is interwoven with an idea of how they ought to go, of what missteps would invalidate the practice.’[xiv]

The Greek-French philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis arguably has done the deepest work on developing the notion of the social imaginary:

‘The imaginary of the society creates for each historical period its singular way of living, seeing and making its own existence’. And: ‘The central imaginary significations of a society are the laces which tie a society together and the forms which define what, for a given society, is “real”.’[xv]

An imaginary affords us to act and collaborate more easily, by offering a consensus view of what reality is and what a shared future should be. It mediates our sense of time and the rate of cultural change, while giving the experience of continuity, predictability and familiarity. It is the reason why we walk through life thinking we know what the world is and how we should act in it. It is energy efficient and it makes belonging easier too – by adopting a ready-made story about reality and not having to debate daily with your tribe members about what is true, real and important. If you did propose new views, it often meant losing your head.

These descriptions of the social imaginary already feel as though they are from a different age, when imaginaries really were backgrounded, quietly holding human societies together.

The Italian cultural critic and media theorist Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi does a good job of capturing the feeling of conditioning and sense of agency the modern Western imaginary brought about. (Note also his reference to the linear temporics we’ll explore later)

‘The future of the moderns had two reassuring qualities. First, it could be known, as the trends of human history could be traced in linear directions, and science could discover the laws of human evolution, which resembled the motion of the planets. Second, the future could be transformed by human will, by industry, economic technique, and political action. The emphasis on the future reaches its peak when economic science pretends to be able to foresee human action, its conflicts and choices. The twentieth century trusted in the future because it trusted in scientists who foretold it, and in policy makers able to make rational decisions.’

He continues:

‘My generation grew up at the peak of this mythological temporalization, and it is very difficult, maybe impossible, to get rid of it, and look at reality without this kind of cultural lens. I’ll never be able to live in accordance with the new reality, no matter how evident, unmistakable, or even dazzling its social planetary trends. These trends seem to be pointing toward the dissipation of the legacy of civilization, based on the philosophy of universal rights.’[xvi]

Bifo’s lament gives a good sense of what it means to be the product (or hostage?) of an era and of the deep-rooted effects an imaginary has on the formation of our individual and collective subjectivity.

‘In short’, says the Italian philosopher Chiara Bottici, ‘if imagination is an individual faculty that we possess, the social imaginary is, by contrast, what possesses us.’[xvii] We are immersed in it.

It is becoming clearer that we are not at all like Kuhn’s scientist. The opposite is the case: we didn’t change the paradigm while the world remained the same – we are in another world and are failing to change the paradigm. With the material world reasserting its existence, the denial of the Real by our solipsistic imaginary is now an existential threat. The idea that we can have infinite growth on a finite planet is perhaps the best illustration of our solipsism – an imaginary divorced from the reality and truths of matter. But we’re failing to install the Anthropocene upgrade because our Wi-Fi connection is busy downloading TikTok marshmallows.

Some have accepted the new reality of entanglement and are giving words to the emergent paradigm and its implications. Thinkers on the Anthropocene, such as Timothy Morton, Bruno Latour and Isabel Stengers, have argued that what was once experienced as background, such as climate, is now presented to us as foreground. The canvas upon which our experience happens, that of time and space, has collapsing into immediacy. Everything is here, happening now – in your face. It turned out that we’d never conquered nature as moderns, nor were we ever separate from it. We just retreated into our minds and the imaginary, entranced by the belief that our mental models were somehow more powerful than reality itself. Now we’re forced to live the ‘Revenge of the Real’, as media theorist Benjamin Bratton coined our harsh waking up to the reality of biological bodies and viruses sharing the same space with us during the Covid-19 pandemic. It turned out that a virus is not a mental construct.[xviii]

We find our cozy imaginary bubble increasingly being punctured by the reality of floods, wild fires or heat waves, whose increasing occurrence are firmly anchoring a dystopian narrative in our minds.[xix] As the Real keeps mercilessly breaching through the veils of our modern solipsism, it forces us to perform frantic mental (as well as economic, financial and political) patchwork to keep despair at bay and our identities intact in the hopes of remaining comfortably held by modernity’s master narratives, such as progress and development.

No, we won’t give up our familiar ways of control just like that. We’ll double down on more of the same failing action-logics like top-down control, more growth or financial innovation, be wowed by the latest technosolutionist promise to clean up the mess from the party we just threw. It won’t work. The party’s over. The hangover called Reality is here.

Zak Stein, in his seminal piece ‘A War Broke Out In Heaven’, drives the point home:

‘Socially constructed realities are exactly what begins to slip away when biology obliges you to enter the liminal. Living between worlds means dealing (again) with reality itself, which is not some featureless totality of oneness, but a complex non-dual whole in which every choice counts and has causal impact.’[xx]

Entering the liminal means living unfoldment, always honoring the reality of entanglement and change. It marks the end of the dualistic logic: the separation of mind and body, human and nature, between cause and effect, distance and linearity. It is the end of modernity as we know it. The entire edifice of the metaphysics of separation on which this modern worldview was built is crumbling. The Anthropocene is the age of entanglement and immediacy and we are called upon to give up our addiction to comforting teleologies like progress and development that allows us our spiritual bypassing.

As humans, we can’t do without an imaginary if we want society to function. So we need to keep an eye on the shaping of our own subjectivity by the imaginary and that of the imaginary’s interface with the natural world. And we need to care for it by carefully crafting the stories, images and ideas we choose to introduce, as well as in which direction the imaginary steers our attention, individually and collectively. The film Don’t Look Up is a brilliant critique of our institutional immunity to change, showing the inability to let disrupting information in, the failure of technosolutionism and the resulting atrophy of our adaptive capacities. Polluting the imaginary with misinformation should perhaps be viewed as dumping toxic waste into a river. It should be cared for and protected and kept healthy like a natural park.

Losing the Real

How did we get here, where did we lose reality? We’ve identified a few things, like the convergence of invasive technology, culture and capitalism. There is also long philosophical tradition of reality-denial, favouring epistemology over ontology in philosophical terms, and conflating the two. The founder of Critical Realism, Roy Bhaskar termed this the epistemic and ontic fallacy:

‘The ontic fallacy, namely that the world determines our knowledge, is the hidden social meaning of the epistemic fallacy. Whereas the latter reduces the world to our knowledge, the ontic fallacy reduces the resulting knowledge to the world: it ontologises, hence naturalises or eternalises our knowledge and makes the social status quo seem permanent and ineluctable.’

My overly simplified spin on this is: we believe the world is the way it is because we experience it that way. And we experience the world that way because we believe it is that way. That’s textbook solipsism. Historians of philosophy usually point to Descartes as the culprit, as he is seen as the father of the mind–body split, the one who collapsed ontology and epistemology with his I think therefore I am. In his sincere efforts to arrive at objective knowledge, thinking became equated with Being, but the former became phenomenologically primary from then on and was picked up by the empiricists Locke and Hume, who added that only what we experience with the senses should be considered true, and onwards via Kant, to the phenomenologists and postmodern linguists. Of these, Wittgenstein sums it up when he commands us to not talk about the world, but to talk about talk of the world. The view that we cannot know reality but only its representations came to underpin much theory in other social disciplines.

Professor of international relations and writer on the Anthropocene David Chandler traces one of the more contemporary applications of this Western bias to the mind of the influential economist Friedrich Hayek:

‘Hayek’s focus on the mind of the subject enabled him to remove the external world as an object of universalist understanding: in effect, he argued that the external world was merely a subjective phenomenological product. The materiality of the external world as a meaningful external object was thereby removed.’[xxi]

Hayek’s neoliberalism[xxii], like Descartes’, was another sincere attempt to arrive at objective knowledge. But here the emphasis was placed on the collective intelligence of markets at the expense of that of the individual, which Hayek saw as possessing a flawed rationality and taking actions based on historical conditioning rather than actual events. This shift of power to the markets deciding what is true, strengthened the causality of collective affairs on individual minds. The removal of the external material world was further fueled by capitalism’s move from material production to the information economy which values production of data and symbolic content with which the business models of internet companies monetise our attention, transfixing us on the marshmallows of semiocapitalism.[xxiii]

Our individual agency too became a story of atrophy and deeper retreat into our minds. In the dominant economic theory of today, we are considered as free and rational individuals, but we are asked to act within choice architectures designed for us by policy makers and entrepreneurs. The term choice architecture refers to the practice of influencing choice by organising the external context in which people make decisions. Navigating these, aided by data from surveillance capitalism, produces a subjectivity that can perhaps be termed the ‘algorithmic self’; a self in the game of optimising for outcomes that are preprogrammed for us as desirable: more stuff and status usually.

The sense of individuality, authenticity and agency which arises from this choice making, seemingly with free will, are then perhaps best seen as second-order, illusory epiphenomena resulting from the enslavement by big tech’s algorithms that, ironically, we ourselves feed and train by using their tools and apps. We’re made complicit in the shrinking of our own world. This narrowing, rolled out over a few centuries and backed up by reality-denying philosophies and economic theory, has added to our imaginary taking on a more solipsistic character.

The Body

The solipsism is not just of our own making, but we are also in a sense hardwired for it as a result of our biological evolution according to Paul Marshall, quoting the neuroanthropologist Merlin Donald:

‘The human brain has co-evolved alongside its cognizing cultures for two million years and has reached a point where it cannot realize its design potential outside of culture. The apparatus of mind itself, and the operational configuration of the brain, which regulates it, are, in significant part, a result of enculturation. Thus the human mind evolves along with the evolution of culture … But the co-evolutionary process has increasingly shifted from cultural evolution being dependent on brain evolution (the early emergence of mimetic culture) to cognitive evolution being ever more dependent on cultural evolution.’[xxiv]

The matter seems to be that we have increasingly started to self-simulate and taken our evolutionary cues from an attentionally demanding cultural reality of our own making, less and less from the material world. This is a good place to continue integrative efforts by including the body and by complementing our understanding of the relationship between the Real, our individual subjectivity and the social imaginary with recent developments in neuroscience; particularly Predictive Processing (PP) and the Free Energy Principle (FEP), the latter formulated by British neuroscientist Karl Friston, who posits that ‘the brain is in the game of optimising its connectivity and dynamics to maximise the evidence for its model of the world.’[xxv]

A working assumption of many schools active in the field of PP is that we are carriers of a mental model of the world and that in some sense we even are this dynamic model that seeks to constantly optimise itself. The social imaginary and the world (as representation) are then not merely ‘out there’, but also can be seen to exist as mental constructs, including that of a self that is brought into relationship with this ‘internalised’ mental model of the ‘outside’ world and other people, seeking evidence for its fittedness and the need for upgrades if there are mismatches between it and reality – so called ‘prediction errors’ which are experienced as surprise.

Bridging first and third person perspectives, the neuroscientist Thomas Metzinger offers an insight into how the imaginary can be seen as an individual and collectively generated dream in this neurophenomenological account:

‘[A] fruitful way of looking at the human brain, therefore, is as a system which, even in ordinary waking states, constantly hallucinates at the world, as a system that constantly lets its internal autonomous simulational dynamics collide with the ongoing flow of sensory input, vigorously dreaming at the world and thereby generating the content of phenomenal experience.’[xxvi]

This is still fairly abstract, although we all know the garden variety of some of the processes in play when we see a face in a cloud. There is no face, just water vapor and a play of light in a particular configuration that lends itself to our anthropomorphising projections. The mechanism is that a primary percept is augmented by a concept and seemingly instantly generates a certain meaning or a different perception, just as you see my words as words and not as ink blots or pixels on a screen.

If we use the language of neuroscience to reframe the issue of the mismatch of our imaginary with the real world, we could say that we are living a collective prediction error.

Copium for the masses: pseudo-agency

We saw that one solution to the unraveling of stable social structures and to steer social processes are to offer choice architectures. We are called to become an ‘autotelic individual’, according to the influential sociologist Anthony Giddens; a subject capable of generating meaning and a destiny for itself, always in control. Throw a rock in Silicon Valley and you are sure to hit the epitome of this way of being in its start-up culture, which is now a global phenomenon with set codes and rules for success – ‘move fast and break things’ being one.[xxvii] Success is modelled by ‘self-made’ tech billionaires who are also the cheerleaders of grind culture. Not so you can become successful like them, but so you will continue to slave away, keeping their unicorns afloat.

Something strange thing is going on; no coercion seems needed. No external discipline is making the worker grind harder, either as a freelancer or as an employee. They are doing it (to) themselves, appearing intrinsically motivated by the promise of becoming the next Elon Musk. Once again, it is the introjection of an imaginary (economic) model of the world, complete with ready-made action protocols, so you can act the best-fitted version of self to that reality – Giddens’ rational, autotelic individual. Merlin Donald’s observation that we’re no longer primarily in dialogue with the real world, but mostly with cultural memes, strongly applies here.

In their analysis of the production of this kind of subjectivity in the neoliberal world order, the scholars David Chandler and Julian Reid sketch out how a logic of constant upgrading to stay fitted to a context of rapid change forces us to live reactive lives, asked to accept the shrinking arena in which our agency still translates into a sense of freedom. The only place in which we can imagine preserving our agency, they suggest, is in our minds and by controlling our bodies:

‘The neoliberal subject is thus a subject at home in a world in which externally orientated projects of transformation are no longer imaginable. A subject for whom work on the self is understood to be liberating and emancipatory; who welcomes governance discourses of empowerment and capacity-building in the knowledge that we are all producers of our world and all share responsibility for its reproduction.’[xxviii]

It’s fair to say that this version of agency can only survive in a highly solipsistic environment at the expense of interpersonal relationships as we retreat deeper into ourselves. We see this logic of upgrading of self in the proliferation of what I term the ‘coping industry’. Dumbed-down mindfulness practices promise to take care of your stress; an app on your phone to tell you how to breathe, eat and sleep; there’s narcissistic pop-sci spirituality that says you create your own reality and thus you can manifest anything you desire. There’s your ‘friend’ on Instagram signaling from a beach in Bali with their hard body that they are fully in control and have mastered the coping game. (You can too, if you do their 10-week program). Many people in the developed world now treat their life as a problem to be solved, focused on self-control, always optimising, strategising and upgrading.

The coping industry has spawned a whole new social class – the Yoga Bourgeoisie[xxix] – herded on by all sorts of influencers, who, as the storm troopers of capitalism are telling us how to be. This class, in cahoots with the exploitative disciplines of marketing and advertising, can now be considered an existential threat, as their function is to keep the dysfunctional show on the road to extinction while feeling like the best version of their quantified selves.

It’s no sign of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society, Jidda Krishnamurti once observed. We all know in our bones that this kind of winning is clearly part of a losing game but we continue playing anyway – if we have the money. Those who can’t afford a tight yoga butt or a trip to the jungle to guzzle some ayahuasca are found in the statistics of the opioid epidemic. In the end it is unbearable to live like that, always shapeshifting, adapting and upgrading in reaction to an imaginary in accelerated breakdown mode. Thus, the counterculture to the Yoga Bourgeoisie is here. Goblin mode was elected Oxford word of the year for 2022. Goblin mode embraces ‘the comforts of depravity’ – the opposite of the Yoga Bourgeoisie’s optimising game.

Personally, I like ‘vibe-shift’, which made Harper Collins’s longlist for word of 2022 and captures the feeling of Unheimlichkeitbrought about by the winning word: Permacrisis. Vibe-shift reflects the dissonance of living in a world that on the surface never had it so good while everything seems to break down. As Bifo articulated before, life for moderns was once underpinned by a feeling of going somewhere. Some sense of direction called progress, that we could harness individually through personal development or building a career. Today, progress is increasingly replaced by a feeling of directionless acceleration and cultural stasis. Mark Fisher declared this phenomenon ‘The slow cancellation of the future.’

Time (between Worlds)

Time doesn’t seem what it used to be. Could there be something going on with time itself? The Tibetan-trained lama Tarthang Tulku certainly thinks so and describes how the ‘momentum of time’ and ‘the mechanism’ makes it impossible to envision alternatives to modernity:

‘This accelerating sameness feeds into a gravity of thinking that makes the momentum of time ever more unstoppable. What is confirmed through this single-minded sameness? It may be the particular manifestations of tradition, such as sacred scripture, authoritative texts, or well-established customs. It may be a discipline or methodology for knowing, such as the scientific method. It may be the various forms of influence exerted by others, or the fundamental stories that confirm personal identity, or the deepest structures of consciousness together with the reality they are suited to pronounce. In each case, the mechanism works in the same way. We find ourselves isolated within the borders of the established model. We cannot know and do not have the answer; cannot think what is new. We move in a narrow circle: patterns of sameness on the surface, the blank numbness of repetition on the interior. Bound to the results of the process, we have no access to the process itself. At most we may sense its operation in a vague dread in the face of the unknown.’[xxx]

Tulku is careful not to put the source of the malaise on the surface, the items in the imaginary, but on our inability to gain access to the process. To use a physics metaphor; what happens when a volume shrinks or more stuff is crammed in? What’s inside heats up, pressure builds, things start to move faster and what is solid melts. Physics also teaches us that closed systems move toward entropy, so decay, death and transformation are perfectly natural phenomena.

Before exploring how to gain access to the process, it’s helpful to first situate us in a bigger picture of where we are, where we may be headed and what we may be participating in. Some cultural commentators state, each in their own terms, that we are in a ‘Time between Worlds’ – moving from one way of being, organising our societies and our relationship to reality, to a new one. Scholars of cultural history and consciousness, such as William Irving Thompson, Ken Wilber, Jean Gebser, David Graeber and David Wengrow, have tried to make sense of the contents, subjectivity of earlier cultural-historical periods, including qualitative changes to a civilisation’s structure, cooperation, practices and sense of selfhood.

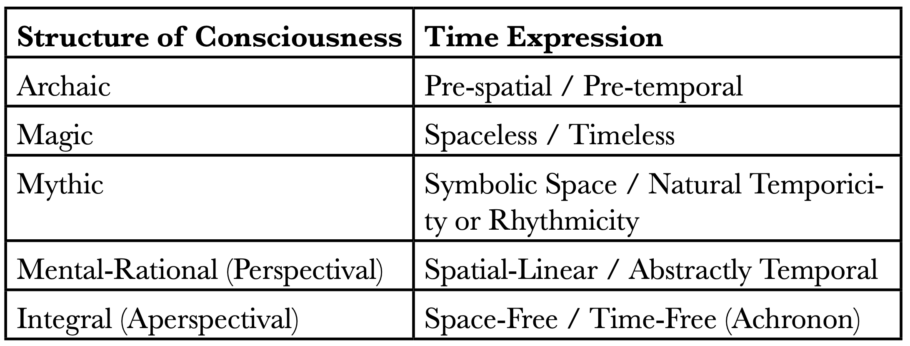

Gebser is interesting in many ways. He speaks to our time and about time itself using the term ‘Temporics’, which he sees as endeavors to ‘concretise time.’ He describes our current historical period as the Mental-Rational, which followed on the Archaic, the Magic and the Mythic. Besides being historical epochs, they also co-arose with, or were the result of, specific ‘structures of consciousness’ (SoC). His clarification of these structures in his prescient work The Ever-Present Origin, is a careful analysis of how social and cultural artefacts are the manifestations of these structures.

I see Gebser’s concept of SoC as deeper than the social imaginary. Computer metaphors are often considered problematic, but the imaginary can perhaps be seen as the implicit knowing of the existence of an Office suite of modernity’s social systems software (spreadsheets for finance and economics, word processing for media, graphics for art and advertising, and so on). Culture is the collective experience of the user interfaces for these apps and what artifacts and practices we produce by using them. Structure of consciousness then is the operating system that holds the deep code of how the totality of software packages are organised and work together coherently.

Obviously, all this functioning relies on a substrate of physical matter, the hardware. A functional, modern user interface requires hardware that is more than a mere heap of atoms and molecules. We need matter that is configured into microchips. Our problem is that our solipsistic software is trying to fix its bugs by rewriting code itself. We’re ‘trying to think our way out’, when what is really needed is a new operating system and a different architecture, which I think needs to be built on new forms of matter that can’t be found within, nor uncovered by, the current imaginary and structure of consciousness.

Gebser says that the Mental-Rational in its current stage is in a ‘deficient form’. I have tried to describe that deficiency through the story of the mismatch of the imaginary with the reality it has itself created. According to Gebser, the structure of consciousness we’re currently ‘mutating’ into is the Integral, which he calls a ‘qualitative change’ and a ‘discontinuous leap’, producing an entirely novel perception of the world and subjectivity.[xxxi] It is beyond the scope of this piece to describe the Integral structure in depth. But for our purposes it’s important to know that, according to Gebser, we also reconnect to ‘Origin’ through the Integral structure. I interpret that term as roughly on par with what wisdom traditions name the Absolute, the Source, the Unmanifest, Brahman, Ein Sof, nondual ground – or God, if you like. A more contemporary spin would be to call it the ‘non-emergent’, as it doesn’t arise out of anything. It just is, which includes non-being.[xxxii]

A clear connection to Origin, from which manifest reality flows into being through the Deep Continuity, was obscured by all prior structures according to Gebser. Especially by the current Mental-Rational one, in which we relate to reality primarily through perspective, abstraction, symbols and representations. This structure of consciousness, which comes with a specific organisation of self, other and world, sets these three apart at a maximal ‘distance’. It has ‘created’ space, as it were. Bring to mind the flat, two-dimensional, Egyptian hieroglyphs and depictions of bodies and life? Now contrast that with the perspective and depth that appeared in Renaissance paintings. These painters saw the world in 3D, space had entered awareness and objects became separate. Gebser says humanity’s consciousness ‘mastered space’ with the Mental-Rational mode.

I argue that we haven’t mastered that other ingredient of reality – time – in the same way. The mastery of which I see as discovering time in its fulness. Like space, we’ll see that spacetime is not fundamental as it is currently conceived of, but is a construct and an enacted outcome of our way of interacting with reality.[xxxiii] A brief history of time follows, using Gebser’s description of how each structure comes with its own time expression.

Figure 1. Adapted from Jeremy Johnson’s Seeing through the World

Time expression refers to the general experience of time that an imaginary embraces, as well as a means to ‘concretise’ it as we mentioned before. To concretise time is the practice of temporics, in Gebsers vernacular: awareness of time as an explicit feature of reality and as active in and constitutive of our type of consciousness. Not only is a specific time expression part of a SoC, but it’s also a deep foundation upon which an imaginary functions and uses to organise society.

Modernity and the Mental-Rational (perspectival) SoC can be said to be characterised by the dominance of a linear way of viewing time – the tripartite structure we seem to live our entire lives through; that of past–present–future. Our experience of ‘now’ flows along it, terminating at death (if you do not believe in an afterlife or reincarnation.) Our way of thinking about change and the future is strongly structured and constrained by this linear temporal order. It has embedded itself deeply in our (collective) psyche, functioning, together with space as the bedrock and limits of our experience.

But time is, in its deeper nature, also an alive force that can’t be constrained. According to Gebser, time is ‘irrupting’ and destabilising our imaginary. The effects of which can be currently felt. The Gebser scholar Jeremy Johnson writes:

‘Gebser points out three phases in which time enters and destabilises the perspectival world: the breaking forth of time, time irruption, and time concretion. The breaking forth of time occurs to us when we are not yet aware of what the phenomenon is; it appears to be happening to us. Time irruption is experienced as the increasing consciousness of time as it irrupts in our cultural phenomenology; the concept of time, clock time and anxiety, time as a force that is speeding up and out of control. Lastly, time concretion is the manifestation of time as an acute phenomenon in our lives, freed – at least partially – from the spatial abstractions of the mental and expressed as a tangible presence and reality.’[xxxiv]

The Integral age is further characterised by Gebser as ‘Aperspectival’ – freedom from perspective – the spatial representation of reality that entered mainstream Western consciousness and is found in Renaissance art. The emergent Integral structure also affords an expanded view of time, which Gebser termed the ‘Achronon’, time-freedom (‘A’ meaning freedom from, not absence of):

‘To the perception of the aperspectival world time appears to be the very fundamental function, and to be of a most complex nature. It manifests itself in accordance with a given consciousness structure and the appropriate possibility of manifestation in its various aspects as clock time, natural time, cosmic or sidereal time; as biological duration, rhythm, meter; as mutation, discontinuity, relativity; as vital dynamics, psychic energy (and thus in a certain sense in the form we call “soul” and the “unconscious”), and as mental dividing. It manifests itself as the unity of past, present, and future; as the creative principle, the power of imagination, as work, and even as “motoricity.” And along with the vital, psychic, biological, cosmic, rational, creative, sociological, and technical aspects of time, we must include-last but not least-physical-geometrical time which is designated as the “fourth dimension.” [xxxv]

As many spiritual practitioners and psychonauts know, there are many ways of experiencing time – our chronoception. What follows is a personal account of an experience of an altered perception of time that took place during a Zen retreat in France. Since then, alternative experiences of time have become commonplace throughout my years of practicing inquiry and often arise co-present with the familiar linear-sequential mode of time.

A few minutes into the kinhin (Zen walking meditation) – happening outside the zendo, on the grounds of the French farm where we were holding our retreat – I was suddenly deeply struck by the beauty of the cathedral-like formation of the tree canopies above me. In that moment of awe my identity and perception shifted – from being a body in the world walking among trees, to being the entire world, my body in it as a part of the totality.

The experience was rich in many ways, but the most striking part of the experience was the expanded perception of time. Back in the meditation hall, I was standing opposite a fellow meditator and could ‘see’ in his face all the ‘preceding’ time enveloped in that moment. I saw both the totality of time and the evolution through regular spacetime that had produced his face. But this perception of spacetime was held in a ‘larger’ timeless and dimensionless space.

‘Seeing’ the depth of the temporal dimension happened through the image of a sort of tunnel or conduit, extending ‘backwards’ from his face, in deep spacetime, to its origin, which seemed to form the limit of my cognition. The Zendo, the spatial element of my first person experience, was no longer hosted within the familiar confines of a three-dimensional world, but was fully open, boundless and in non-spatial space. My perception of the man was not just of his own individual history and lifetime, but appeared as a continuum of everybody that had come through his genetic-cultural lineage, as if even the totality, or at least much of humanity, came together in the single face of the man standing less than three meters from me on a black meditation mat. This composite was not sectioned, nor was it an undifferentiated amalgam of him and others. His total being was an unbroken whole, in which the usual temporal demarcations of birth and death did not apply. It was a coherent but differentiated totality affording room for an individual self.

That experience of time feels close to how Gebser describes it – a fully alive and creative force that cannot be contained within the narrow sector of space we have carved out for ourselves in our perspectival consciousness. I believe we are currently living through Gebser’s second phase of time’s irruption. Time is starting to ‘happen to us’, and also foregrounding itself with all kinds of disruptive effects. The Christian mystic Cynthia Bourgeault, commenting on Gebser, completes the picture of how this irruption is experienced in our time between worlds and as the breakdown of the Mental-Rational structure of consciousness:

‘When the mental structure enters deficient mode, … Paradigms multiply, sometimes dizzyingly, along with the telltale siren call toward meta-synthesis: a “grand theory of everything” that engulfs all paradigms, all components, all “quadrants” in a single comprehensive overlay. The naming and articulating goes on compulsively and at breakneck speed as if, in some sort of magical reversion, we’ve allowed ourselves to believe that by correctly framing the situation, we have everything under control.’[xxxvi]

If I understand Bourgeault correctly, (and I think she understands Gebser better than some) she means that we do not need more neoliberal ‘levelling up’ – growing a mind so complex or a consciousness so big, that it can embrace and handle all the complexity of our systems and map all the chains of causality of the metacrisis so we can fix it. Saying we need to grow into a higher level of consciousness to deal with our issues may just be applying the same deficient mental-rational malware that got us into this mess.

Ontological insurgency

What then, oh Ivo, wise one? Tell us what we should do! That attitude of giving up power to experts or gurus (whether Buddha or Boris Johnson) to save us, is more modern malware. True, this age is screaming out for wisdom and it is there, but wisdom schools are often insular, generally unconcerned with social issues and often stuck in tradition. And teachings and practices are primarily focused on the individual’s suffering and realisation. That’s fine, but it is limited and excludes deep inquiry into other realms, the ontology of social reality for example. On the other side, the social sciences generally lack this deeper ontology, is either materialist or constructivist, and mostly reasons through linear-causal views of reality, seeing issues through modern mental-rational frameworks.

The change-the-individual-to-change-society-approach leaves out both the elephant in the room and much of the room itself – the social imaginary and its causal powers. When it comes to changing, we’re generally no match for it. The imaginary ‘has us’.

Spiritual warriors who come back from retreat know all too well the experience of re-entry into society and the rapid loss of whatever state of expanded identity was acquired. Give it a day and we’re back to our old self. Retreat spaces and monasteries are set up for this reason, so you are out of the social imaginary with its pressures of entrainment. These spaces are designed on a principle of functional ignorance, so other perceptions can foreground themselves in consciousness. It works, but it’s analogous to doing science in a box. As soon as we leave the closed retreat system and enter the open one of society, the blissful results of our spiritual experiments prove unsustainable.

So alternative approaches are needed to step into the practice gap of social ontology and to inquire into the structures, our agency and effect of our culture’s narratives. I do not see that work as spiritual, it merely relies on methods and insights that are found in spiritual traditions. Nor is the aim individual realisation, but merely to become a better perceiver of the real when we are trying to effect change in the world and to prepare people that they will be changed by doing it. Thus, it demands we drop our self-obsessed neoliberal work-on-ourselves stance, or our spiritual trophy hunting and go straight into what I call The Messh – the entangled, extended, enacted, embedded, embodied, nondual and nonlinear dynamic totality.

That may sound overwhelming. But, says the independent scholar Bonnitta Roy:[xxxvii]

‘we are not so much working for greater systemic reach or to identify all the links in an enormous causal chain; rather we need to closely examine the metaphysical operating system of our minds, and participate in the creative emergence of a new structure of consciousness.’

She adds that the metamorphosis needed is driven by pressures that run counter to the modern mind’s ‘upward path’ and argues that:

‘it operates through what David Chandler calls “counter systemic approaches” which destabilise the modern imaginaries of “progress”, “civilisation” and “development” while challenging our “fixed and empty framework of time and space with ourselves at the centre”.’[xxxviii]

Roy brings much together here. Just as we can’t work purely on ourselves, we also can no longer continue to work ‘on’ the world. That means further widening the infamous subject–object divide, placing humans further away from others, matter and nature. It means fueling the mechanisms that are driving the Meta-crisis. It also means that we need to reimagine what we consider to be a human being. This imagining cannot be done rationally. It must be done experientially, reflexively and iteratively; and without self-concern. As Octavia Butler said:

‘All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you.’

Imaginal Qualia

The key is to identify or design counter systemic practices that help to free us and can get us from stuckness to collective unfolding. Below a look at one approach, focusing on what I call Imaginal Qualia. We think these are fundamental to our human world and how it must function. These are social axioms or big, implicit collective commitments that come as a package deal with a host of social action protocols that we can use, like the start-up entrepreneur. So they can be seen as the attractors and modulators through which we enact the social imaginary and keep it cathected with our life energy.

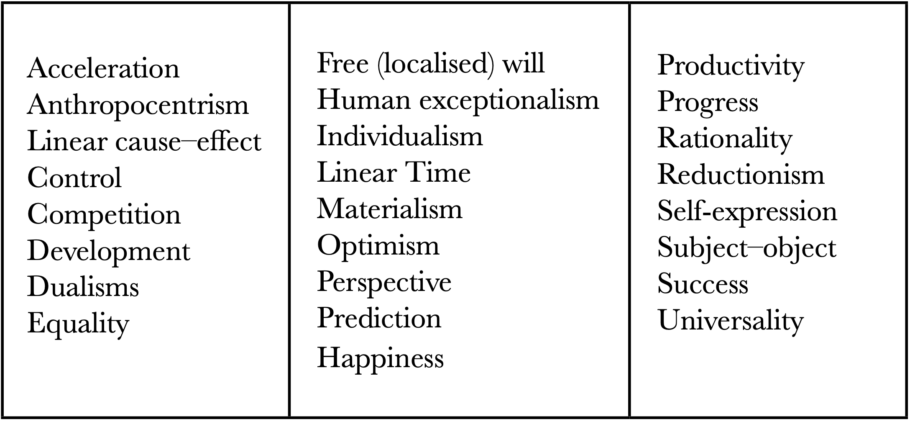

Now we can start touching parts of the Machine. Just as the ego-self can be explored as an ecology of psychological parts, so can we approach modernity and its imaginal qualia: notions such as progress, the separate individual and our linear sense of time. Below a non-exhaustive list of some of our darlings.

Table 1. Some Imaginal Qualia

I chose these items for their accessibility, the ‘access to the process’ that Tulku emphasised above. They don’t form a neat taxonomy, but contain a mix of truths, useful symbolism and nonsense. For instance: they are either neurophenomenologicallly grounded experiences such as the subject–object divide; cultural myths, now part of our personal striving or collective identity, such as success and equality. Some, like acceleration, are epiphenomena, intrinsic and unavoidable outcomes of processes that we set in motion by historic design decisions, such as the investment-debt-growth cycle which means that the need for growth is inescapably baked into our current economic system. Or debt, lending on interest means having to print money exponentially to repay it all. Materialism is an assumption about the nature of reality on which we base practices and many other ideas about the world. They can be social-economic action protocols, like prediction and competition to guide our seeking. There are the heuristics and methods for sensemaking or scientific inquiry such as reductionism. They may serve as temporal-developmental introjected teleologies that afford meaning, guide action and capture our collective imagination like progress and development.

The critical realist philosopher Roy Bhaskar might say much of this list belongs to the realm of the ‘Demi-real’ – useful, but ultimately human constructs, like money and laws. But the Demi-real also contains superstitions and is full of cognitive errors. We call it sunrise and is something we witness as real, but it is the earth turning. Unfortunately, it can’t be simply ignored because, even if things are complete fabrications (like a stolen election), they still have the power to, say, get people to storm a capitol building. Dualism is a big one. We know from quantum science that nothing is separate, not an object, but this is what we see and base many of our actions on. Some IQ’s, like (linear) time, may have some actual metaphysical substance or dynamism as Gebser pointed out. The main thing to grasp is that we are actually practising enactive metaphysics through the qualia, our language and by applying our models on the world we cocreate it. They have what can be called ‘imaginal causality’.[xxxix] Lastly, the Imaginal Qualia also form an end point, the horizon of our social imagination. Who would we be if all these don’t exist? So sincere inquiry comes at a risk of losing our comforting illusions, but we may find new truths. Evan Thompson succinctly describes what we might encounter: ‘all illusions are constructions, but not all constructions are illusions.’

Changing the Subjectmatter

Where do we start? Always right where we are now, because there is no alternative.

As I reflect on my work and the slow progress I’m making on this essay, I become curious about the ever-lurking feelings of guilt around work, and how my self-esteem and productivity seem strongly correlated. Upon further reflection, I realise that in some sense I am always feeling watched. This is obviously my inner critic, which seems to use as a rod for my back a bigger, introjected cultural Protestant–Calvinist story around productivity and how idleness loses us our ticket to heaven. I never consciously accepted this narrative, it’s just seems that is the way things are. How did this come to be? A memory emerges from when I was about ten years old. I am at home playing with my brother, having fun and forgetting all about time, while we were tasked with some chores. All of a sudden, my parents come home and yank us out of our playful state of innocence, which was quickly replaced by guilt, following their verbal and silent energetic disapproval of our nonproductive bodies.

Through many hours of practicing spiritual inquiry, I know how to work with constellations of parts and how not to focus merely on the emotional content that exists between images of self, other or world, but to ‘hold’ the totality and its constituent parts. Let’s call them the ‘Judging God’ and the ‘Lazy Self in this case.

I sense how identification with the Lazy Self and being judged impacts me emotionally and somatically. Especially seeing the core message that love is conditional (dependent on productivity) triggers mildly painful contractions in the heart and solar plexus region. The inquiry leads me to deeper questions around personal will and power. Where is (my) will? With the Judging God, or the deficient self-image of the one who should be productive? Sensing into this confusion and seeing the interplay of the two images, their roles, and feeling the emotional-energetic charge needed to uphold the constellation, I feel the parts dissolve and myself becoming more centred and whole and there is less inner conflict around the ownership of will.

This dissolving happens frequently in inquiry, when an object-relation, as some schools of depth psychology call it, is held in a bigger space of presence and none of the elements and their story are identified with. Also notice that in my memory, as a child I relate to my parents not really as individuals but as messengers of culture. They are not authentic, but trying to instill in me their internalised social imaginary, with a style of parenting and cultural values of obedience and a particular Protestant work ethic. And they implicitly communicate, (as surrogate gods) that love is conditional, dependent on productivity and falling in line with set expectations. In a sense, they are channeling the imaginary as God’s will to me.

This example is also where the personal and the (Western) universal meet. My experience is also a microcosm of a thread of psychocultural evolution that has played out over millennia: that of the internalisation of the Will. Roughly, it is the path from God’s external will to a personal, interiorised will, situated within and constitutive of the modern individual – another qualium of our imaginary.[xl] As long as I am identified with, or reject, either pole of this binary object-relation, the judge and judged, I am also ensnared by the Calvinist/capitalist imaginary and in a constant battle for my will. This positioning of qualities such as Will in the ecology of the self, or framed differently – as the boundary plays of structure, culture and agency, is ongoing in its movement and constantly altering our sense of selfhood.

With sustained inquiry, seeing through our historical conditioning, disentangling ourselves from the imaginary and metabolising the social-mental constructs, we can land in a deeper state of presence with a real-time awareness of the pressures of the imaginary. Take the following verbal account from Shayla Wright, a fellow traveler in Bonnitta Roy’s Pop-Up School:

‘When I was reading The Dawn of Everything[xli], all of a sudden I experienced a full-bodied experience of how conditioned my subjectivity has been by all the historical notions infused into us. It was the background of my whole sense of who we are as humans and what is possible. I could feel how the text of that book started to deconstruct it all. And there was this incredible sense of liberation and movement. I had no idea how conditioned my subjectivity was.’

This account is beyond what an author seeking to change minds can hope for. The book Shayla refers to, The Dawn of Everything, is an alternative (pre)history of humanity. It tells the story of how creative ancient humans were and that alternative imaginaries and cultures were living alongside each other, with very different world views and social practices. It is not the standard version of history that says we were basically savages and then, voila, reason and science came along and a few millennia of cultural evolution gave birth to Steven Pinker to tell us how amazing we modern Westerners are and that everything is going to get better all the time.

Shayla is a seasoned practitioner in both intersubjective and work on the individual self. Experiences like hers usually only follow after someone is sufficiently steeped in emptiness practice, has seen through the mind’s symbolic interface with the world, and has developed a deep empathy and an open heart capable of resonance. New stories or images can strike deeply in our soul, allowing this kind of transformative impact.

This dropping away of the deep conditioning by the social imaginary is, at best, a side effect of most kinds of spiritual work and usually not its aim. Recall Shayla’s surprise: ‘I had no idea how conditioned my subjectivity was.’ That’s because most inner work focuses on the personality and goes ‘inward’ rather than ‘out’ to include our imaginary as a domain of causality and practice.[xlii] The squeaky wheel of ego-suffering continues to get all the grease. Most do not (yet) heed the insights of 4E cognitive science and predictive processing, that we’re extended and embedded, that we enact not just an ego self-construct, but a total configuration of Self-Other-World. And, as in Zen, hardly any intersubjective practices are found in traditional wisdom schools – a critical design omission that needs to be addressed if we want spiritual work to be truly in service of social change.